Deep Steps: A Generative AI Step Sequencer

Last year during the Music and Machine Learning course, I began explore incorporating the autoencoder into a musical step sequencer. I wrote about this initial work here and here. My jumping off point was the similarity between a step sequencer and using many-hot encoding for representing music. The work there used Pure Data for the sequencer and GUI interactions communicating with a Python script running the ML models. My other intention was to provide a format, interface and dataset pipeline which could potentially be accessible for music producers. As such, I chose audio loops as the format for training data due to their ubiquity in electronic music production workflows.

Deep Steps

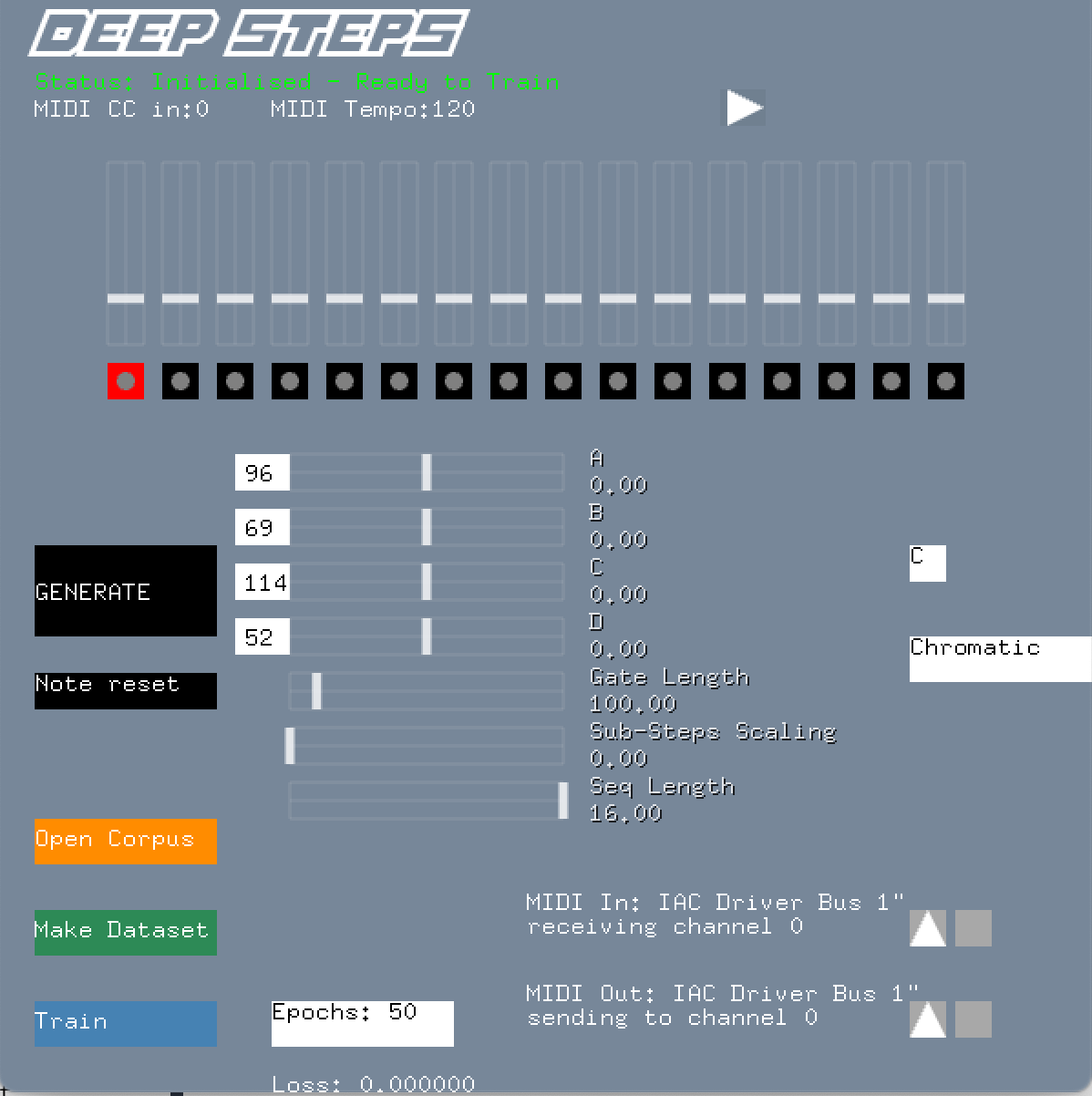

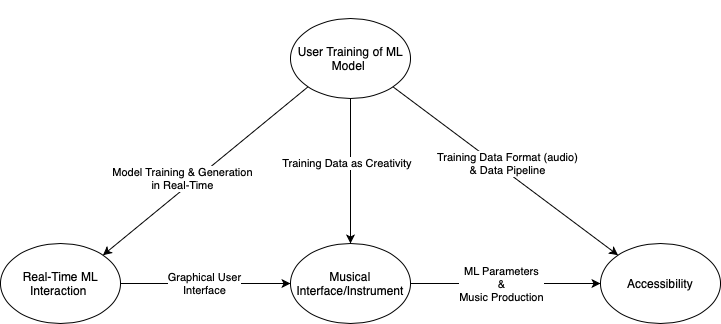

For my MCT Masters thesis I chose to develop this work into a more unified implementation. This meant bringing all the aspects together into a single interface that would be potentially usable for electronic music producers. In doing so, the intention was to have model training and model generation being part of a real-time musical interaction. Rather than provide a fixed pre-trained model, users would instead use their own training data to customise the model for their own intentions and styles. I decided to call this combination of a deep learning model and a step sequencer, Deep Steps.

New Interactions

The traditional machine learning pipeline is to train and optimise a model and then deploy it for use. This is appropriate for many situations where use of such a model is appropriate but it is debatable for applications involving creativity. A comparison can be made to the evolution of drum machines from having fixed sounds and rhythms in their early days to now having full user control over programming and timbre.

In developing Deep Steps as a GUI-based interactive system, the intention was to expose some machine learning parameters to user control. Though numerous systems exist which use machine learning and deep learning models interactively, these often focus on the means of control for triggering and steering a model’s generative output. In creating an accessible framework for training an ML model on the user’s own data (audio loops), the intention is to explore the potential for this interaction as part of creativity. In a similar way to how Generative Music is a practice of system building as a form of creativity, could the selection and use of training data and parameters for model training also become part of the creative process?

Implementation

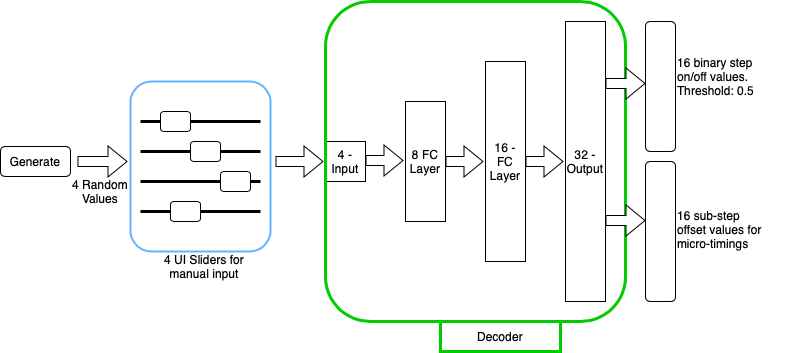

Deep Steps was developed as a stand alone application using the openFrameworks C++ creative toolkit. This allowed for the creation of the GUI, embedding of Pure Data and the compiling of the application itself. The machine learning model was an autoencoder as before. Rather than use a large library like Tensorflow, I instead adapted code from the ML-From-Scratch library which features examples of low-level implementations of ML algorithms using Numpy. For audio analysis of onsets in the training data I used the aubio library’s C++ framework.

The model generates material by having values fed through its decoder stage either through the GUI generate button or through the A, B, C, D sliders.

The source code for Deep Steps is available here

Evaluation

Deep Steps was evaluated two times. After a first round of development, it was evaluated in a short workshop-based user study where 11 participants used the application under controlled conditions and then responded to questionnaires. The intention of this was to test the core principals, functionality and usability of the system. Thankfully, these were all mostly validated.

Deep Steps was then distributed to three music producers to use as part of their music making for a week. The participants were then interviewed to capture their user experiences.

Overall, the findings from the evaluations found Deep Steps to be usable and indeed provided an accessible interface for interaction with machine learning parameters. Training data as an engaging interaction and a part of the creative process was evident in the feedback. The participants’ feedback also highlighted several areas where the software could be improved to make it more appealing for future adoption and long-term engagement. A key theme here was the extra required to engage with the ML processes, especially when existing tools such as randomisers can potentially do a comparable job with less effort. This is a recurring point of friction for these types of implementations which to some extent can be viewed as simply re-inventing an existing algorithmic process.

In creating a GUI to make the ML processes accessible, what I had also done was to hide them away behind the interface. One recommendation was to offer a visualisation of these processes. For instance, the processing of the onset data could be visualised through waveform displays. The feeding forward of the data through the decoder to generate material could also be visualised. This could be used to illustrate the causal relationship of the sliders, which many users reported as feeling like an unsatisfying and arbitrary feeling interaction.

The findings overall are generally positive with Deep Steps representing a functional proof-of-concept for its intentions and design principals.

Demonstration

Finally, here is Deep Steps in action. Here, I am using Deep Steps for rhythmic triggers in my Eurorack modular synth. I am not using the pitch controls in the application, instead looping random voltages from elsewhere in the modular system. I am controlling the models generative output via a MIDI controller with knobs mapped to the four ‘‘latent dimension’’ sliders to pass values into the decoder.