A Rhythmic Sequencer Driven by a Stacked Autoencoder

A Partially-Automated, Autoencoder-Driven, Generative Step-Sequencer

Following on from the previous blog posts on autoencoders, this post will take a look at implementing a step sequencer for melodic musical parts but with its rhythmic aspect driven by a generative “stacked autoencoder” model. Beyond the technicalities, the project also aimed to explore methods whereby generative AI in music could be made more accessible to music practitioners. This meant that firstly, the training data pipeline needed to be simple and accessible for the average music producer to use. Secondly, it necessitated a structure which was computationally light enough that training and inference could be run on a consumer computer and was fast enough to not interfere with the creative process.

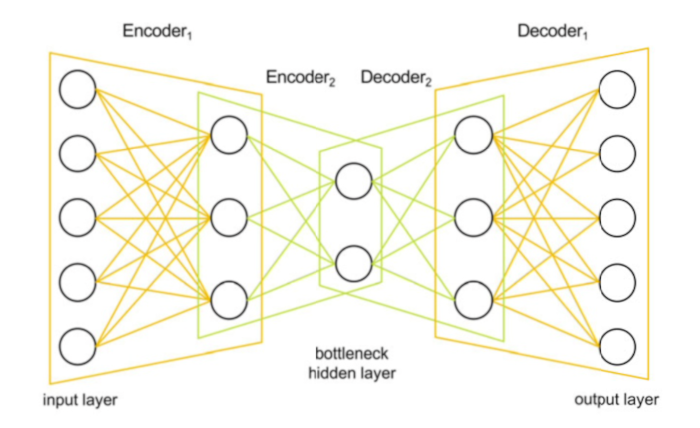

Stacked Autoencoder

Simply put, a “stacked” autoencoder can be thought of as a traditional autoencoder architecture with a greater number of hidden layers. This means that the data goes through several stages of encoding before it reaches the latent layer and a corresponding greater number of decoding layers until it reaches the output.

Briot (2020), explains the advantage of this for music generation as,

“The chain of encoders will increasingly compress data and extract higher-level features… They are also useful for music generation… This is because the innermost hidden layer, sometimes named the bottleneck hidden layer, provides a compact and high-level encoding (embedding) as a seed for generation (by the chain of decoders)”

This technique of feeding new, user input-able information into the “bottleneck layer” is the basis for the generative aspect of this project.

Training

The training data pipeline for this project needed to represent a methodology which could be made accessible to on-the-ground music producers. Most electronic music practioners will cite having extensive libraries of audio samples and loops. There are also huge amounts free and commercially products of royalty-free loops available to practioners.

Training a neural network on audio presents challenges however. Feeding a neural network with raw digital audio is inappropriate as the computational load is too large. Furthermore extracting meaningful, musical and useful features from audio is a task requiring expertise beyond the expectation of the average music practioner.

As the sole concern of the model is rhythm, the training data was processed to extract rhythmic transient/onset information. This was then encoded as a symbolic representation of two musical bars with a resolution of 16th notes. This resulted in binary lists representing 32-step sequences where a 1 denoted a rhythmic event and a 0 denoted a “rest”.

An example from my dataset of this: [1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

We usually imagine step-sequences moving horizontally left-to-right. Returning to Briot’s diagram above of the stacked autoencoder, if you imagine the sequence turned vertically and each step fed in as a separate input to that structure, then you have an idea of how the model is given this representation of the data.

The result of this is two-fold. Firstly, a format of training data which is freely accessible to music practioners can be used to train the model. Secondly, the architecture of the autoencoder is computationally very light and can be trained and utilised very quickly.

The Human Aspect

In opposition to systems employing AI for the creation of more and more complete systems for automatic music generation, this project aimed to instead purposely leave room for the human musician.

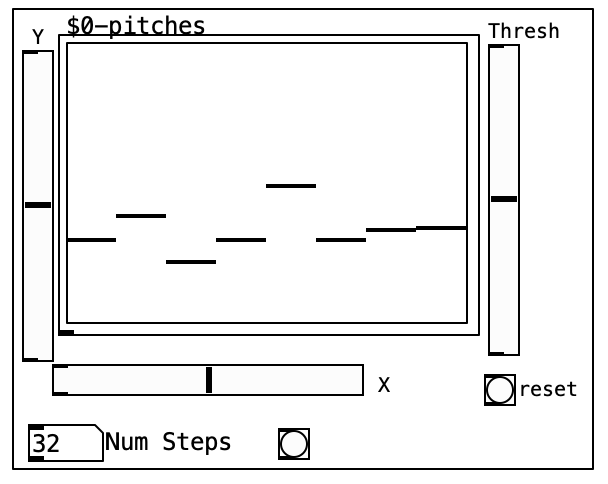

As such, this sequencer offers only a “partially-automated” functionality. While the AI model is responsible for generating rhythmic information, pitch information is left for the human, as are several ways of altering how the inferred data is used. Below is the current user-interface for the sequencer and an explanation of the various controls.

X, Y These are the primary AI-focused user controls. These are for the values to be passed into the “bottleneck layer” and thus generate the rhythmic information. This layer was purposely kept to 2-dimensions as it presents an intuitive representation to the user. Another term for the ‘bottleneck layer” is “latent space”, connoting ideas of a physical space of possibility. This concept is also used in the now-discontinued but open source Mutable Instruments Grids Eurorack module, where it is referred to as “Topographical” sequencing.

Thresh When generating new rhythmic patterns, the model outputs values between 0 and 1. Therefore, the output has a threshold value for what is and is not considered a rhythmic event. By default, this is 0.5 but by opening the parameter to the user, they are able a further level of control over the sequence.

Pitches & Num Steps These represent controls often found on conventional step-sequencers. The user inputs the musical pitches to be stepped through as well as the length in steps of the repeated sequence.

Future Work

In order for this process to be truly accessible and implementable for the wider world of electronic music practioners, further work is required. Currently the model’s training and inference happen in Python via Jupyter Notebook, while the UI exists in Pure Data with OSC being used to communicate between the two. Ideally, the entire process would exist within a single environment with the addition of a user interface for the training process.

This project has however achieved many of the primary goals set out for it. Furthermore, the need for lightweight, rapidly trainable and accessible models will likely continue as generative AI becomes more commonplace and more musicians become open to the idea of “AI assistants” being involved in the creative process.

References

Briot, J.-P., Hadjeres, G., & Pachet, F.-D. (2020). Deep Learning Techniques for Music Generation (1st ed. 2020., p. 1 online resource (XXVIII, 284 p. 143 illu, 91 illu in color.)). Springer International Publishing. Available from: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-70163-9