Strung Along: an extended violin for real-time accompaniment generation and timbral control

Introduction

For my thesis project, I designed and developed Strung Along, a violin based interactive music system which can accompany the violinist (me) in real time by generating chords, while also allowing for timbral, volume and chord voicing control through modulating the force applied through the bow.

The system is borne from my interest in two types of violin music; self-accompanying solo violin repertoire like this and this, and string chamber music like this. The system aims to offer something of the incredible feeling of being musically in synchrony with other musicians, while also offering the intimate control of timbre and volume that solo violin repertoire affords.

Read on to find out how I went about it.

A Tale of Two Sub-Systems

Strung Along consists of two sub-systems, which are integrated into the final system. They are:

- A chord generation sub-system, which generates chords as MIDI notes to accompany a melody played in real time.

- A bow tracking sub-system, which allows for the way the violinist uses the bow to be tracked in real time, and then used to affect the timbre of the sound engine, and the chord generation.

Chord Generation Sub-System

The premise of the chord generation sub-system is quite simple; one plays a note of a melody, and the system generates a suitable chord to go with it (and, hopefully, works with the ones it generated previously too). By repeating this process of multiple melody notes, we can generate a sequence of chords to accompany the melody. Even better, we get to do it in real time - it’s like a string orchestra in your pocket!

Background

Chord progressions are a fundamental aspect of many musical genres, and researchers have been developing systems to generate them using machine learning for decades. Such systems can be applied an a wide range of contexts, from harmonising existing melodies, suggesting alternative chords in pre-composed progressions, to use in interactive systems for live performance.

Many early chord generation systems were designed to harmonise Bach Chorales. These chorales (the very mention of which will raise the blood pressure of anyone who remembers learning figured bass in music theory classes) are a useful judge of chord generation systems, as they offer a very concrete set of rules that determine whether the harmony is correct. These systems were generally offline and static - the user would feed in a melody, and receive back a suitable harmony in some representation

Many more recent systems generate chords for a variety of use cases. ChordRipple aims to help novice composers break outside of rigid harmonic boxes by suggesting alternative chords during composition, while a system proposed by Garoufis et al. for use in live performance allows users to direct an evolving chord progression by selecting a chord from multiple options.

A common thread among these systems is the way in which they represent chords. Typically, this is done using a ‘chord vocabulary’ - effectively a pre-determined list of the chords known by the system, and which it is able to generate. These vocabularies can be very small, consisting of only 12 major and 12 minor chords in the case of Lim et al., or rather large, consisting of over 100 chords in the case of ChordRipple. In machine learning lingo, we call such systems ‘classification’ systems as their output is one or several options from a fixed set of ‘classes’, each of which represents a chord.

Design & Implementation

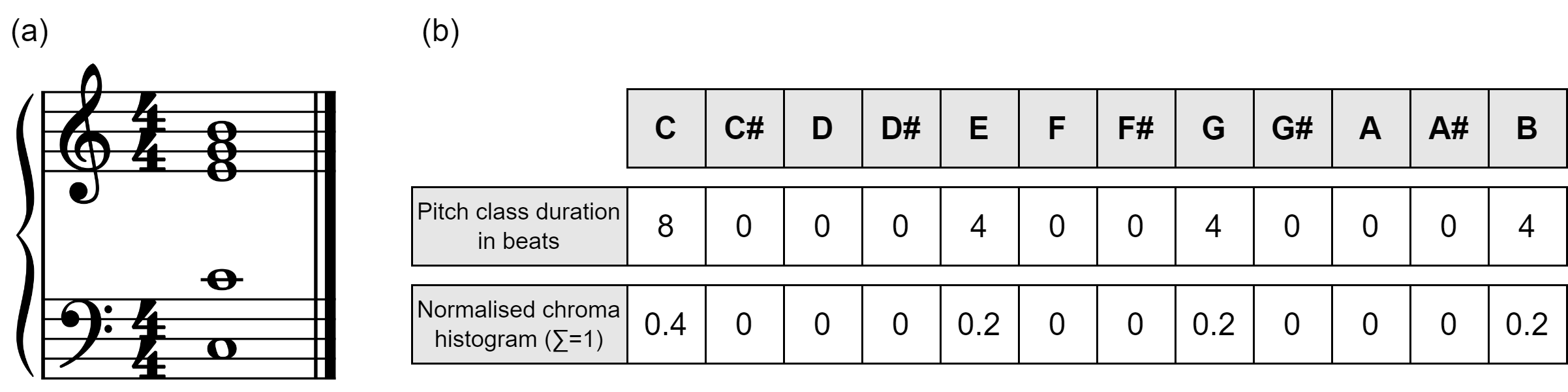

The chord generation sub-system in Strung Along aims to buck this trend by instead representing chords using regression machine learning techniques. Rather than selecting an appropriate chord from a pre-defined set, a chord in this sub-system is represented using a chroma histogram, which is effectively a list of 12 floating point numbers, with each one corresponding to a degree of the chromatic scale (i.e., tonic, minor second, major second, minor third, etc) above a certain root note. Each value in the histogram is determined by the amount of that pitch class in a given set of notes over which the histogram is calculated. The image below shows a Cmaj7 chord, and how it is then represented as a chroma histogram.

I propose two key advantages to such an approach.

Firstly, this approach is not limited by a chord vocabulary, as all the information needed to reconstruct the chord is contained in some form in the chroma histogram. This makes the system more flexible, as it does not need to be retrained to add new chords, while also allowing the number of different chords it can generate to be theoretically endless.

Secondly, the chroma histogram can also encode some basic information about how the chord was voiced, which is conspiciously absent from many of the other approaches mentioned above. The histogram can tell us not only which pitch classes are present in the music it represents, but also something about the quantity or presence of each in the music. In the example above, the C note is used twice in the chord as opposed to every other note which are only used once, so that note aquires double the value of the others in the chroma histogram. Assuming that notes that are used more often are more important to the chord, we can infer some aspects of chord voicing from the histogram, while using only a simple list of 12 numbers.

The machine learning model at the core of this sub-system is trained to generate these chroma histograms. For each note of a melody, it generates a histograms for the chord to accompany that melody note, and then voices it into a set of MIDI notes which are sounded using a software synthesiser. Each newly generated chroma histogram is influenced by the eight previous melody notes and generated histograms. This allows the sub-system to not only generate a chord that works harmonically with a given melody note, but also one that fits with the chords that preceded it.

Bow Tracking Sub-System

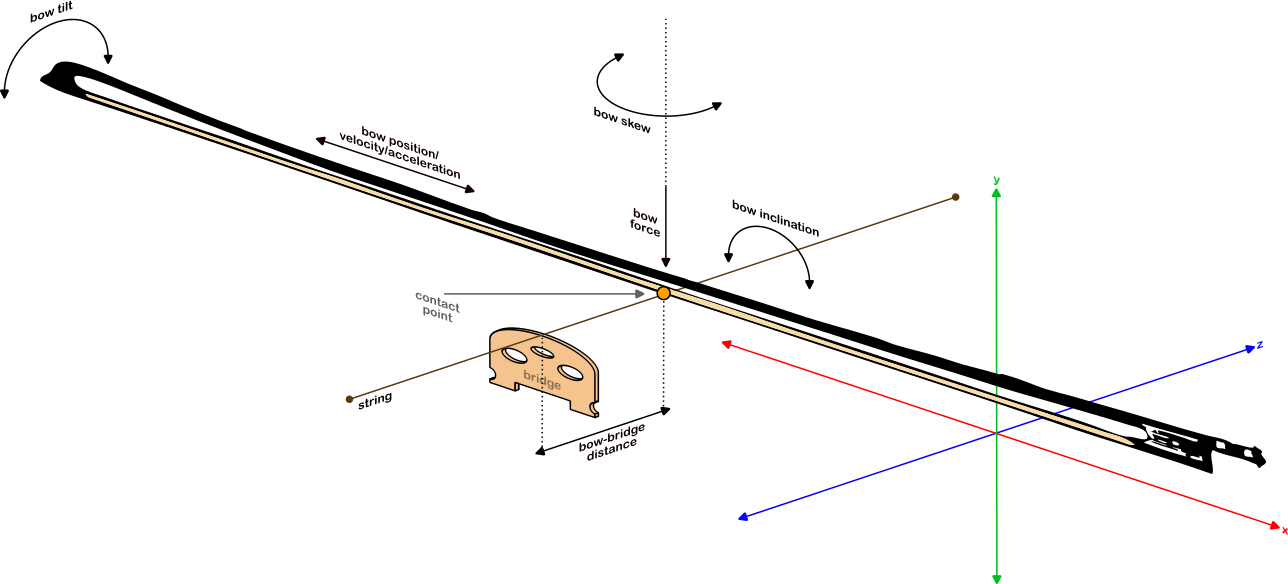

For a violinist or other bowed string player, the way in which they use the bow is most often described through gestures and techniques, like staccato, legato, or spiccato. However, it is also possible to describe bowing technique in scientific terms through a set of positions, rotations, and forces that describe how the bow interacts with the strings of the instrument. These are visualised in the image below.

The bow tracking sub-system adapts an existing approach proposed by Pardue et al. to tracking bow position and bow force. This approach uses four distance sensors which are mounted to the underside of the bow stick at different positions along the bow length, facing towards the bow hair. As force is applied downwards through the bow onto the string, the bow deflects around the contact point, reducing the distance between the bow hair and bow stick at each sensor location. The amount of deflection at each point is determined by the combination of bow position and bow force, such that each combination theoretically results in a unique combination of sensor distances.

We can leverage this fact to train a small machine learning model which, given the distances readings from the four sensors, predicts the bow position and bow force. The bow tracking sub-system of Strung Along does just this in real time, meaning it can be used as a mapping parameter in the combined system.

Creating Strung Along

Coming soon…

Evaluation

Coming soon…

Conclusion

Coming soon…

See It In Action

Take a look at a brief performance using Strung Along here: