Reinforcement learning for use in cross-adaptive audio processing

Reinforcement learning for use in cross-adaptive audio processing

This blog post is a brief summary of my thesis work. The style is meant to be informal, and as such, I’ve left out references and other formalities. The full thesis is available here

Øyvind Brandtsegg was my supervisor.

Abstract

This thesis is a study of reinforcement learning as a possible method for finding mappings in cross-adaptive audio effects. The context of a cross-adaptive performance session is framed as a reinforcement learning environment, in which the idea is to modify one audio signal by the features of another. The results show that reinforcement learning is a feasible way to generate such mappings. Still, there are affordances of using reinforcement learning for this purpose that are yet to be explored. The thesis also proposes a system architecture design that allows for real-time performance with the machine learning agent but is yet to be adequately implemented and tested. Future work could look into how to integrate the system in musical practice and to extend the cross-adaptive reinforcement learning environment to incorporate human feedback in the learning process.

Background

This thesis builds upon the research project titled “Cross-adaptive processing as musical intervention,” led by the Music Technology Group at the Department of Music at NTNU from 2016 to 2018. The research project studied musical performance sessions where cross-adaptive techniques for audio processing were utilized and evaluated. An adaptive audio effect is a combination of a sound transformation with a time-varying adaptive control. Cross-adaptive audio effects are a specialized form of adaptive audio effects where the effect parameters that operate on one signal are modulated by one or more audio features of an external audio signal. This creates new forms of musical interactions between the performers. An example of a cross-adaptive processing session that took place as part of the research project was when the vocalist Maja S. Ratkje was performing with the drummer Siv Kjenstad. The amplitude of the vocals reduced the reverb size of Kjenstad’s drums, and the amplitude of the drums reduced the delay feedback on Ratkje’s vocals. This example was recorded and can be listened to in the first video (from 08:00 minutes) on the webpage from one of the seminars that were held as part of the research project. As you can imagine, the resulting effect is that whenever either of the musicians stops performing, the other performers’ audio output takes up the whole sonic image on stage, either by a large reverb or long feedback.

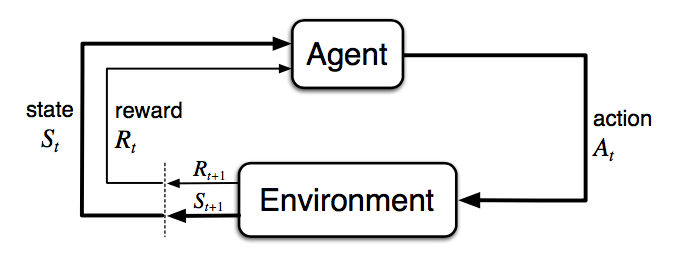

One challenge in designing cross-adaptive processing scenarios is finding out how audio features should be mapped to effect parameters, since there are so many possibilities. Øyvind Brandtsegg (my supervisor) addressed this issue as part of the research project, and proposed that machine learning potentially could be a way of creating mappings at a higher level than manually connecting features to effect parameters. This challenge is what motivated my thesis project, i.e., how we can find interesting mappings in cross-adaptive audio effects without having to manually search through them all. In parallel, I had been interested in reinforcement learning, and how it could be applied in music technology. Reinforcement learning is an area of machine learning that deals with how intelligent agents can learn from interacting with an environment. The reinforcement learning loop consists of an agent that observes an environment, takes actions, and gets a reward based on how good or bad the action taken was. The reward is distributed from a reward function, which is a function of the state of the environment. This reward function is defined by the creator of the environment. The figure below illustrates the reinforcement learning cycle.

After some early discussions with my supervisor about what the objective for my thesis should be, we ended up with trying to use reinforcement learning to find interesting mappings in cross-adaptive audio effects. In essence, this meant that I had to develop a software that let a reinforcement learning agent learn mappings from the features of one audio signal to the effect parameters of another audio signal. Because the goal of cross-adaptive processing is to use it in a live music context, a secondary goal was to make the system useable in real-time scenarios with audio streams.

Methods and implementation

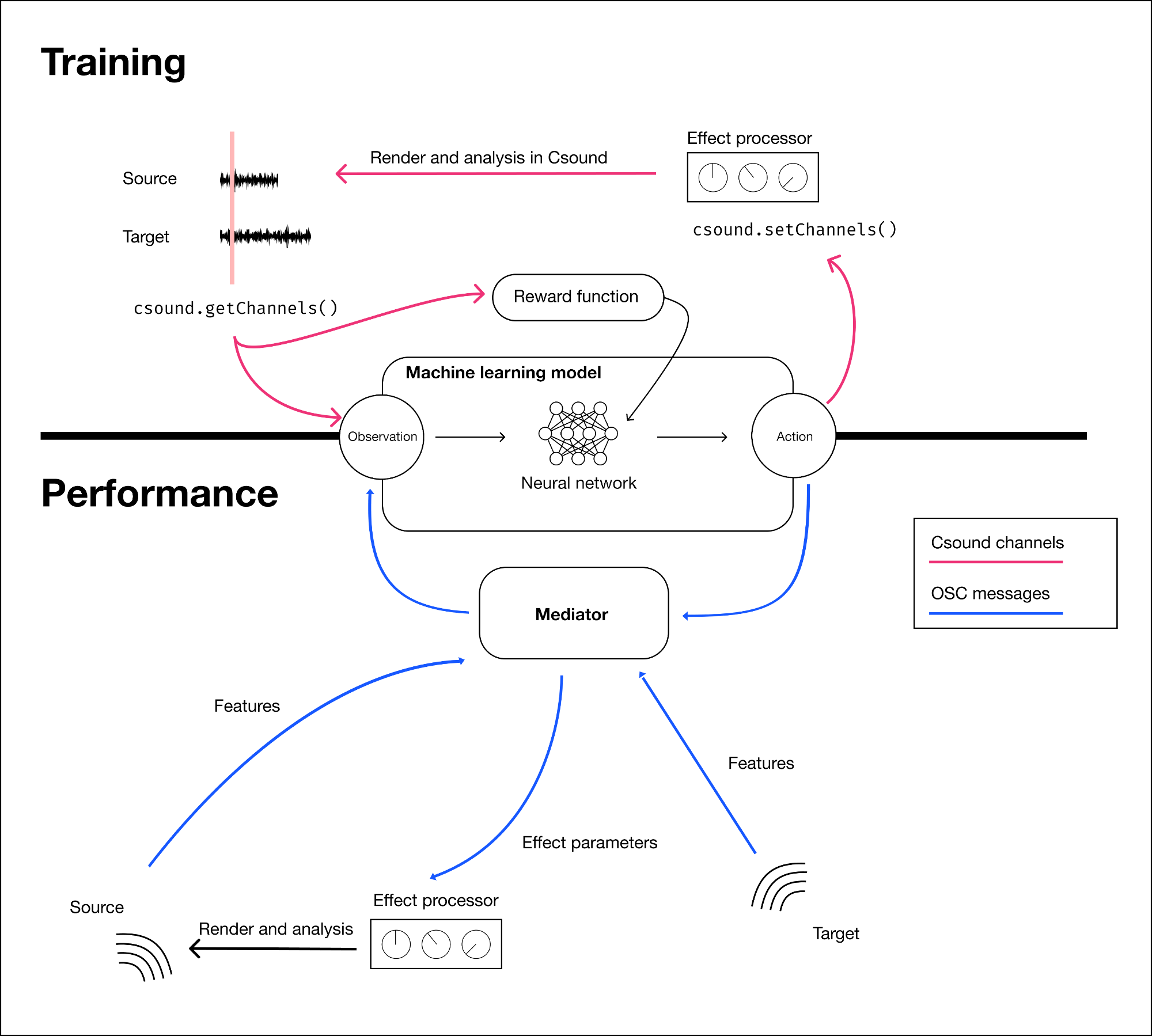

The central part of the work in this thesis was to develop the reinforcement learning environment that was needed to bridge reinforcement learning and cross-adaptive processing. The reinforcement learning part was implemented in Python, and the digital signal processing was done in Csound. Some of the Csound code was reused from previous projects in the cross-adaptive research project, such as Øyvind Brandtsegg’s featexmod. The figure below illustrates the system architecture for training and live performance with the model, where the main difference is how the machine learning module communicates with the Csound rendering processes. The source code is available in a GitHub repository for anyone who wants to have a look.

To be able to measure degrees of success in the project, a quantifiable objective was set: to process a source audio sample in such a way that it has the greatest possible similarity with the target audio sample. A sample of white noise was used as source, and the famous “Amen break” was used as target. The effect that was used to produce the results was a low-pass filter with additional distortion control. Even though that effect is quite versatile as a sound-shaping tool, it has obvious constraints as to how much it is capable of modifying a given sound, especially in terms of harmonic components.

The evaluation of the project consisted of evaluating results that the prototype produced according to several conditions, such as which features were used in the analysis during training, or the degree of randomness in the exploration of possible actions.

Results

More background material would have to be provided to describe the various results produced in the thesis properly. The interested reader can look into the complete thesis linked to at the beginning of this post. However, some of the more notable results were how feature selection impacted the training of the machine learning model, and how the model generalized to new sounds.

Source and target audio samples

The following samples were used as source and target.

Source: noise.wav

Target: amen_drum_break.wav

Feature selection

Features: [RMS]

One model was trained only on the RMS values of the source and target sounds. The result sounds like this:

Features: [RMS, pitch, spectral centroid, spectral spread, spectral flatness, spectral flux]

Another model was trained with additional features. The resulting model did a lot better at representing the frequency content in the target audio sample than the prior model did.

Generalizability to new sounds

An unheard sample was used as source (instead of white noise) to test how a model trained on shaping white noise into the Amen break generalizes to new sounds.

The new source

The result

Real-time

As mentioned in the abstract, designing a system that would work in live settings was a secondary goal of this project. For “live mode”, the two audio streams were rendered in separate processes, communicating with the machine learning module over OSC. The overall system was built in a way that enabled sending and receiving audio features and effect parameter mappings over OSC, but I didn’t find enough time to implement a proper way of synchronizing the streams. Thus, there is work that remains in synchronizing the OSC streams to be able to utilize the software in live performances.

The current implementation of live mode suffers from packets arriving at different times at the machine learning module, thus creating a sort of “jitter” in the parameter updates. The resulting output can be heard in the following audio sample (NB! this sample is very distorted, so it is advisable to reduce the volume before pressing play):

Conclusion and future work

This thesis investigated how a simplified version of a cross-adaptive performance scenario can be modeled as a reinforcement learning environment to create mappings in cross-adaptive audio effects. The contributions of this thesis are the research and development of an open-source system capable of creating mappings in cross-adaptive audio effects with techniques from reinforcement learning. Even though the implemented system should be considered a prototype, this thesis demonstrates that reinforcement learning is a viable technique for creating mappings in cross-adaptive audio effects. The crude implementation of asynchronous real-time inference shows that it should be feasible to use the system in real-time over OSC.

There is a lot left to be done in figuring out how the cross-adaptive environment best is brought into a performance and production context. This work would require systematic user testing. To further explore the affordances of reinforcement learning, the cross-adaptive reinforcement learning environment could be extended to incorporate human feedback in the learning process. Future work should also look into the generalizability of the results by combining other effects and feature extractors.