Learning to sequence drums

Sequencing drums with reinforcement learning

The motivation for this project was to start to explore interactive use of machine learning in music, with the intention to continue the work in my master thesis. The specific goal of this project has been to train a neu- ral network to respond to incoming MIDI sequences of one instrument with appropriate MIDI sequences of another instrument.

The background for the idea was a personal desire for a system that could be able to respond to choices I make in my digital music production. Often, I find myself sampling from a variety of different random functions to produce interesting parameter combinations or patterns. However, I generally have to make quite a few attempts before finding something that sounds meaningful.

In this project I wanted to figure out if it was possible to create a software that could do a bit better than random, to augment the human-computer interaction in a production setting.

Source code: https://github.com/ulrikah/rave

Reinforcement learning

To tackle the problem at hand, I decided to apply techniques from reinforcement learning, a form of machine learning that I have been wanting to learn more about for some time. Reinforcement learning is concerned with learning software agents an action policy that they should use to act in an environment with the goal of maximizing a cumulative reward. The reward is given by the environment in which the agent is acting. One example of reinforcement learning could be a game in which a software agent learns to play tic-tac-toe against a human opponent only by evaluating the reward (e.g. 1 for victory and 0 for loss) after repeated rounds of playing with a human agent. For a game such as tic-tac-toe, in which both the action space and the observation space are small and discrete sets, iterating through all the game states and calculating the optimal policy is a trivial task. In more complex environments, it can be either impossible or too computationally expensive to derive the policy explicitly. In such scenarios, neural networks can be used as approximators for the policy function, since they have the property of being universal function approximators [4]. This has led to recent breakthroughs for the field of reinforcement learning, such as the ability to learn agents to play several Atari games only by looking at the raw pixel values [5].

Implementation

The code for the project can be found at: https://github.com/ulrikah/rave. After installing the dependencies in conda.yml, training the model can be done by executing

python main.py train

This produces a checkpoint in the checkpoints/ folder. Subsequent testing of the model can be done by running

python main.py test --checkpoint checkpoints/<checkpoint>

Modelling the environment

Trying to build a custom reinforcement learning system comes with the cost of having to design and develop and environment in which your agent can act. To build the environment, I created a class which inherits from gym.Env (see the gym docs) and implements the required methods and properties.

The environment I built is more conceptual than the typical gym game environments. At its core, it has a function for calculating the reward given a (state, action) pair, and a function called step for performing iterations and updating its internal state. It also has a render function which simply prints the sequence as a string. However, render is supposed to be extended with some functionality for converting the binary sequence to MIDI and doing I/O operations over a MIDI port.

The metric I used to calculate the reward was simply defined as the normalised sum of the absolute difference between the two patterns. As an example, given the following inputs:

x o o o x o o o x o o o x o o o [kick]

o x x x o x x x o x x x o x x x [snare]

the environment yields the maximum reward of 1.0. In other words, for most of the time I tried to make the network learn the snare pattern above. This metric is in itself not interesting in a machine learning context, since it would be easy to define a much simpler algorithm to optimize the program to generate such sequences. However, it was very useful to work with a simple metric to evaluate whether or not the network learned the way I hoped it would.

I wanted to test out a variety of metrics in my project, but I didn’t get that far. I would like to try implement at least one of the techniques from Shmulevich and Povel [7] to incorporate a metric of rhythmic complexity. In that way, given a kick pattern as input, I could potentially be able to learn a neural network to play the most complicated appropriate snare pattern as the output.

Evaluation

To evaluate my model, I made a script that would run n iterations of the environments step function and blindly take the argmax of the softmax output the neural network as the action. The softmax activation function returns a probability distribution over the different steps in the sequence. Taking the argmax of softmax just means picking the step in the sequence that the neural network has given the highest probability for. During training of the network, I sampled from the softmax distribution in order to explore different options.

Considering that my network only can toggle one step at a time, it should take some iterations before it finds the optimal sequence.

I created two test scenarios which should yield rewards in the two extremes of the reward range (−1, 1) according to the metric I used. In both scenarios, the kick sequence is initialized to the standard 4/4 sequence.

The model that I used to test here was trained for 300 episodes.

Best case scenario

x o o o x o o o x o o o x o o o [kick]

o x x x o x x x o x x x o x x x [snare]

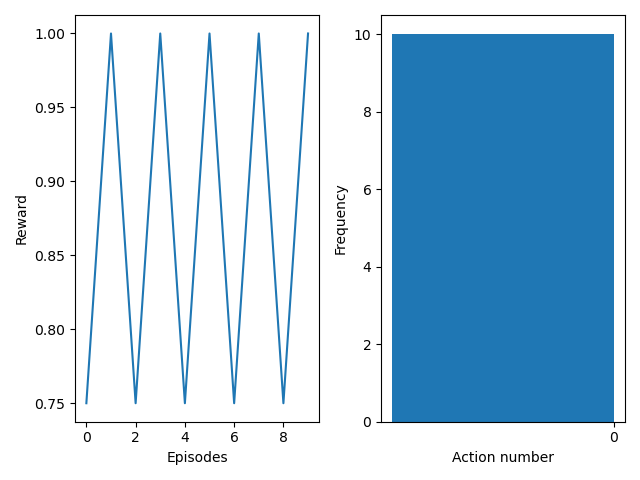

This scenario yields the maximum reward of 1.0 by default. This means that the network hopefully should avoid modifying the snare sequence, as it is already in its most optimal state. This very model was trained without the option to avoid toggling (i.e. by only outputting values for each of the 8 on/off steps in the snare sequence). As a consequence, it is expected that the network oscillates between the rewards 0.75 and 1.0.

Figure 1 demonstrates that the network is able to avoid modifying an optimal sequence, which is what we wanted. And interesting side effect is that the network only uses one of the steps to toggle on/off (a bit difficult to see in the graph). It may seem like the network has learned that if it is in a balanced state, it should only toggle one of the steps repeatedly.

Worst case scenario

In the worst case scenario, I initialize the snare sequence to be equal to the kick sequence:

x o o o x o o o x o o o x o o o [kick]

x o o o x o o o x o o o x o o o [snare]

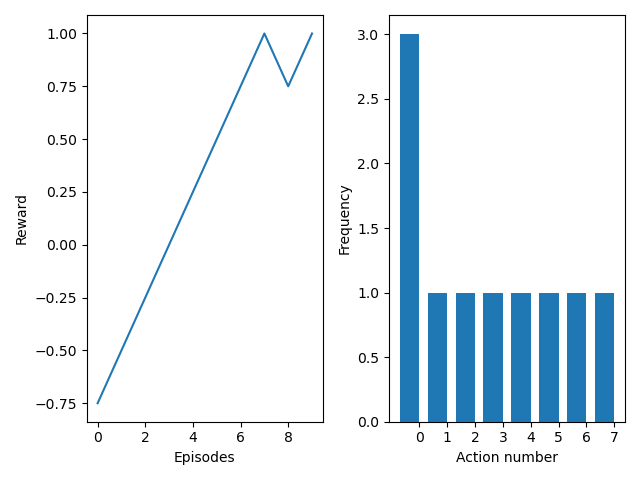

The expected result of this scenario is that the network is able to modify the sequence into a sequence that ends up yielding rewards 0.75 and 1.0.

Figure 2 shows 10 forward passes through the network. The network manages to modify the snare sequence into a sequence that yields positive results very fast. After it has reached the optimal state, we can see the same oscillation between 0.75 and 1.0 that we observe in figure 1.

Reflection

Throughout the project, I spent a lot of time trying to understand why the neural network I created failed to learn the representation I wanted it to learn.

At the very end of the project, I realized that I was only considering the average reward per episode as the metric of performance. This doesn’t make much sense given that I initialized the snare sequence randomly every time I reset the environment, which was done at the start of every episode. The problem with this approach is that it doesn’t measure how well the network performs in terms of correcting a bad sequence. Looking back, I probably should have measured the delta reward per episode, i.e. if the episode yielded a more positive reward at the end of the episode than at the beginning.

Future work

Future work on this project will involve exploring other metrics for defining the reward. I think an ideal solution would be to have the reward be defined by some weighted sum of multiple metrics, one of them being for instance to look at rhythmic complexity. In a production scenario, it would be interesting to let the user define which metrics that the agent should learn from, and this might be parameters that the musician could play with in a live context.

The system as it is today don’t render the binary sequences in a meaningful way. There is no formal relation to MIDI in the code, which obviously is something I would need to work on. Some of the next steps would be to formalize the agents a bit more, and integrate them with existing MIDI libraries such as pretty-midi or mido.

I would also need to design the algorithm more carefully to allow for flexible sequence lengths. One idea could be to train the network on long sequences (e.g. 512 or 1024 notes), and to do some smart resampling of shorter sequences.

Exploring how to extend this program to multiple voices would also be interest- ing to look at. Ideally, I would like to have multiple agents all learning from each other in a swarm-like manner to investigate what those sort of interations might produce. For this purpose, looking at Multi-Agent Actor-Critic [12] might be interesting.

At last, the system would need to be redesigned in a way that makes it applicable. This would potentially mean to export the model into something that could be read by other environments, and e.g. use it as part of a Juce or Max plugin (through Node For Max) in Ableton Live.

References

- Qichao Lan, Jim Tørresen, and Alexander Refsum Jensenius. RaveForce: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Environment for Music. In Proceedings of the SMC Conferences, pages 217–222. Society for Sound and Music Computing, 2019.

- Francisco Bernardo, Chris Kiefer, and Thor Magnusson. An AudioWorklet- based Signal Engine for a Live Coding Language Ecosystem. In Proceedings of Web Audio Conference (WAC-2019).

- Lonce Wyse. Mechanisms of Artistic Creativity in Deep Learning Neural Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.00321, 2019.

- Michael A. Nielsen. Neural networks and deep learning, volume 25. Deter- mination press San Francisco, CA, USA:, 2015.

- Volodymyr Mnih, Koray Kavukcuoglu, David Silver, Alex Graves, Ioannis Antonoglou, Daan Wierstra, and Martin Riedmiller. Playing Atari with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.5602, 2013.

- Muhan Li. Machin. https://github.com/iffiX/machin, 2020.

- Ilya Shmulevich and D.-J. Povel. Rhythm complexity measures for music pattern recognition. In 1998 IEEE Second Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing (Cat. No. 98EX175), pages 167–172. IEEE, 1998.

- Adam Paszke. Reinforcement learning DQN tutorial. https://pytorch. org/tutorials/intermediate/reinforcement_q_learning.html, 2020.

- Chris Yoon. deep-q-networks. https://github.com/cyoon1729/ deep-Q-networks, 2019.

- Greg Brockman, Vicki Cheung, Ludwig Pettersson, Jonas Schneider, John Schulman, Jie Tang, and Wo jciech Zaremba. Op enAI Gym. arXiv:1606.01540 cs., June 2016. arXiv: 1606.01540.

- Adam Paszke, Sam Gross, Francisco Massa, Adam Lerer, James Bradbury, Gregory Chanan, Trevor Killeen, Zeming Lin, Natalia Gimelshein, Luca Antiga, Alban Desmaison, Andreas Kopf, Edward Yang, Zachary DeVito, Martin Raison, Alykhan Tejani, Sasank Chilamkurthy, Benoit Steiner, Lu Fang, Junjie Bai, and Soumith Chintala. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In H. Wallach, H. Larochelle, A. Beygelzimer, F. d’Alch ́e-Buc, E. Fox, and R. Garnett, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32, pages 8024–8035. Curran Associates, Inc., 2019.

- Ryan Lowe, Yi I. Wu, Aviv Tamar, Jean Harb, OpenAI Pieter Abbeel, and Igor Mordatch. Multi-agent actor-critic for mixed cooperative-competitive environments. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 6379–6390, 2017.