Prototyping musical instruments

During the HCI course, we examined the instruments prototypes built as part of the physical computing hackathon. This blog post is a summary of our reflections of prototyping musical instruments in the name of recycling, a project we called Orchestrash. Where the previous blog post discuss the technicalities of prototyping instruments in a physical computing environment, this one will examine Orchestrash from an HCI point of view.

Introduction

The accessibility of open source platforms such as Bela and Pure Data is boosting the creation of new musical instruments. The relationship between sensor technologies and visual programming provide great possibilities in the conception of interactivity, having an expressive impact on the contemporary music production (Poupyrev et al., 2001). Creative uses of such technologies arise from the versatility in the user experience while developing with these tools. Equally important, the simplicity of these mechanisms tend to decentralise the production of devices to the artistic expression, giving more democratic perspectives to the production of musical devices.

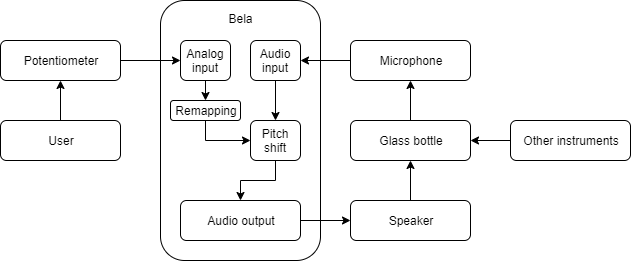

The system

The system presented here consists of a four instruments ensemble aiming to make music out of trash. The instruments were designed to be simple interactive interfaces, with distinct roles and frequency bandwidths, and consisted of a looper/sequencer, bass, drone and a synth. To make sure everyone was playing in the same key, we constrained the three melodic instruments to play within the C minor scale.

Our interpretation of the theme was to a large extent related to the notion of reusing sounds, through techniques such as feedback, sampling and looping. We decided that we also should try to use recyclable materials as sound sources and controllers as much as possible, e.g. by recording sounds from a plastic water bottle and a cleaned-out yoghurt tray. Using objects that don’t traditionally belong in music performance turned out to foster different creative approaches during prototyping and while performing. Looking back, this could very well be related to Cook’s principle that “Everyday objects suggest amusing controllers” (Cook, 2017). Moving away from traditional controllers and sounds liberated us in the creative process, and also augmented the improvisational structure of the performance.

Performance

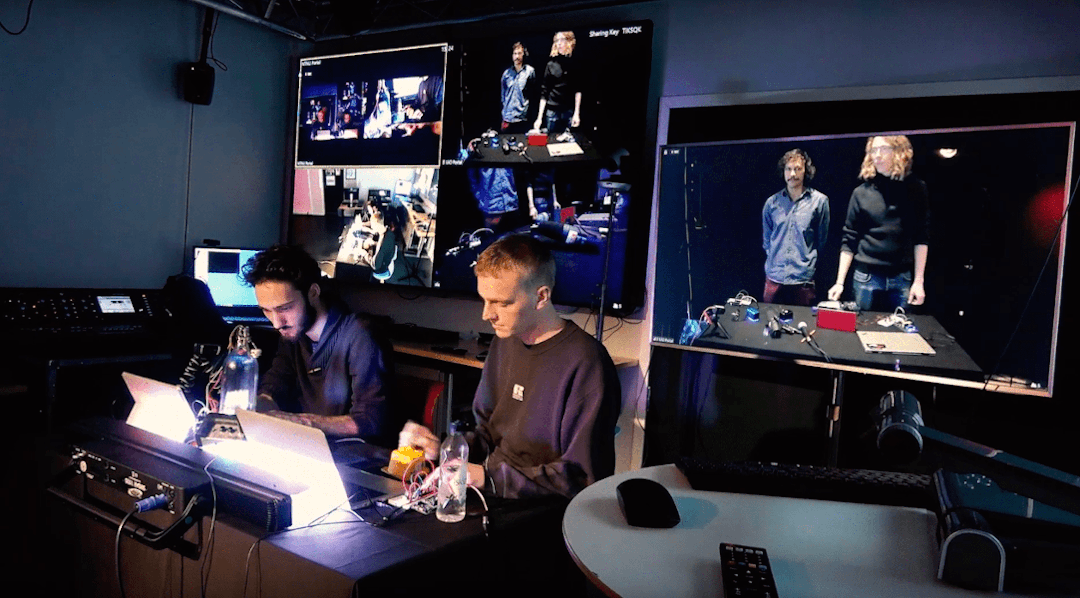

Considering that the telematic system we used when performing the music (networked musical performance over LOLA) had such a high impact on the musical expression, it is fair to say that the inherent properties of the telematic system became a big part of the performance in total. This builds on the idea of “musicking” elaborated in Small (1998), where it is not only the musical performance of the artists, but all the properties of the system that play into the action-perception loop and thereby plays a part in the entire “musicking” performance.

References

- Ivan Poupyrev, Michael J Lyons, Sidney Fels, et al. New interfaces for musical expression. In CHI’01 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages 491–492. ACM, 2001.

- Christopher Small. Musicking. In Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. University Press of New England. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8195-2257-3, 1998

- Perry Cook. Principles for designing computer music controllers. In Alexander Refsum Jensenius and Michael J Lyons, editors, A NIME Reader: Fifteen Years of New Interfaces for Musical Expression, pages 1–13. Springer, 2017