How To Save The World In Three Chords

Brought to you by Aleks ‘Ack-Ack’ Tidemann and Paul ‘Ray Gun’ Koenig

The Dramaturgy, if you will

For MCT4044 (Spatial Audio), we were tasked with the . . . task of designing, recording and mixing a spatialized audio composition. The composition was expected to have a clear dramaturgy, a unifying and coherent concept and realization, loads of action, excitement, and a mind-blowing climax that will simply blast your socks into next week. (I’m paraphrasing the requirements here.)

Shamelessly ripping off the 1996 cult-classic film ‘Mars Attacks!’, we decided to tell our harrowing story-in-sound as a dramatic tale of alien invasion and eventual repulsion.

Because the unrelenting lethality of Slim Whitman’s voice is by now well known, and also because neither I nor Aleks can yodel, we decided that our fearless (and perhaps clueless) hero would take a slightly different form.

In the guise of a possibly-homeless street performer, our doughty busker repels the aliens with a combination of harmonica, guitar, and questionable lyrics about snorting coke off of someone’s garage floor (we take no responsibility for his poor life-choices).

To effectively tell the story, we paid super careful attention to its Aural Architecture as described by Blesser (Blesser, Barry et al 2008), in particular the concept of Navigational Spatiality.

In other words, we strove to create an aural environment whereby the listener could visualize the represented space through sound. Nifty, eh?

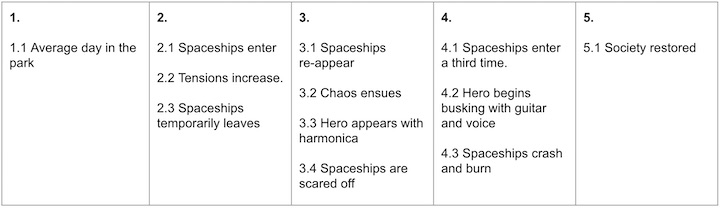

Figure 1 shows our storyboard/timeline.

Sound-Field Recordings

We made a total of seven sound-field recordings in outdoor environments around Blindern and Marienlyst. Each recording was approximately two-and-a-half minutes long, and captured an array of environmental sounds ranging from basketballs bouncing, children shrieking, birds yelling, and cars larking about to lunatics stomping through puddles while playing the harmonica.

This seemed like just the perfect, idyllic sort of scene to be obliterated by malice-filled alien beings.

Figure 2 shows one of our microphone setups, just outside the backdoor of the Fysikkbygning. Since we couldn’t find a deadcat (wind-shield) for the rather expensive Soundfield microphone, we improvised with a lua, or “deadhat”, which was loosely-woven and somewhat hairy, for a lua. It worked well enough, and no doubt better than an old wool sock, though this was not tested.

Making The Spaceships

Using a Korg MS-20 synth, Aleks created some great spaceship sounds for the project. Ever keeping in the forefront of his mind the concept of immersivity through spacial presence (Roads 2015, p. 278) he toiled for days or minutes to fashion immersivity from the rank dust of insensate sound-oscillator ejaculate, via the technique of having multiple sound files for a single source.

Five different mono audio files were created to represent the same object at different locations, as follows: Sound 1: Appearing Craft. Sound 2: Hovering Craft. Sound 3: Craft Near Listener. Sound 4: Craft Flying Away. Sound 5: Craft Plummeting Towards Ground.

Chaos Ensues

What would an alien attack be without shrieking humans? For this sound effect, we used samples of actual shrieking humans that Iggy (the Samplemaster) sent along, including one of Barney from The Simpsons, episode 142 (we suspect). To create the aural illusion of people running about in blind, abject terror, we implemented collective rotation (using the master azimuth feature of the IEM multiencoder) to make the voices move around. To further increase tension, we increased the volume and proximity of the alien presence to create a more oppressive effect.

Enter: Our Savior (Not Jesus… OR IS HE??)

For the hero guy, I made a simple mono recording in a specially designed acoustic chamber (my bedroom) of a suitable family-friendly song appropriate to the project. We then created the sonic effect of our hero-musician traveling through the soundscape through the use of source-panning automation, EQ and volume. Everywhere our hero goes, the music-intolerant aliens lose control of their spacecraft, crash and explode, much like the composition professors at my old alma mater when I approached them with a piece of tonal music written purely for the pleasure of ‘note-based’ music.

In this way we immerse our subject in the environment through processing (Barrett 2020; Roads 2015).

(Explosion sounds courtesy of Freesound.com.)

The World, Saved

And so, the world is yet again saved by the power of music. We enjoyed the project, and felt like we were successful in telling a fairly action-packed story in just over three minutes. Had we had more time, there’s a lot more we could have done to increase the realism of the environment, from more careful (re. very time-consuming) automation of eq and effects, to adding more sounds and smells (burnt alien in 3rd order smell-o-sonics, anyone?) to complete the illusion.

But, much like our hobo hero, I’m afraid we gotta move on. There’s a garage floor somewhere with our name on it.

References

Barrett, Natasha. (2020) “Spatial Music Composition,” n.d., 15.

Blesser, Barry, Spalter. (2008) “Aural Architecture: The Missing Link.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 124(4). doi: 2525–2525. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4782966.

Roads, C. (2015) Composing Electronic Music: A New Aesthetic. Oxford University Press.