Get unstressed with Stress-less

1. Introduction

1. 1 Background to the project

The heart is one of the most important parts of the body. It is not by chance that it was already studied during the ancient times, for example by Aristotle (The History of the Heart, n.d.). Since William Harvey’s discovery in the 17th century, there have been even more interests in studying the heart (Ribatti, 2009). One of the interesting features of the heart is the heart rates. The heart rate is an important indication of the status of a person’s health, and there have been efforts to show how the heart rate could be entrained to acoustic stimulus (Saperston, 1993). More recently, fast paced music was shown to entrain the heart rate (Hong et al., 2011). However, these outcomes have been debated and experimentally illustrated (drum beats were used as a stimulus) that there is no strong relationship between acoustic stimulus and heart rate (Mütze et al., 2018). Before we settle on that, it is also important to note that the fetal heart was able to be entrained to the mother’s heart rate through the fetal auditory system (Ivanov et al., 2009). Perhaps, the studies where unnatural stimulus was used, such as complex and fast paced music and drum strokes, should be re-evaluated against experimental studies where more natural acoustic stimulus (i.e., heartbeat) was used. To the best of our knowledge, there has not been a study where real heartbeats or realistically simulated heartbeats through (either recordings or artificially constructed through audio programming) were used to entrain the heart rates.

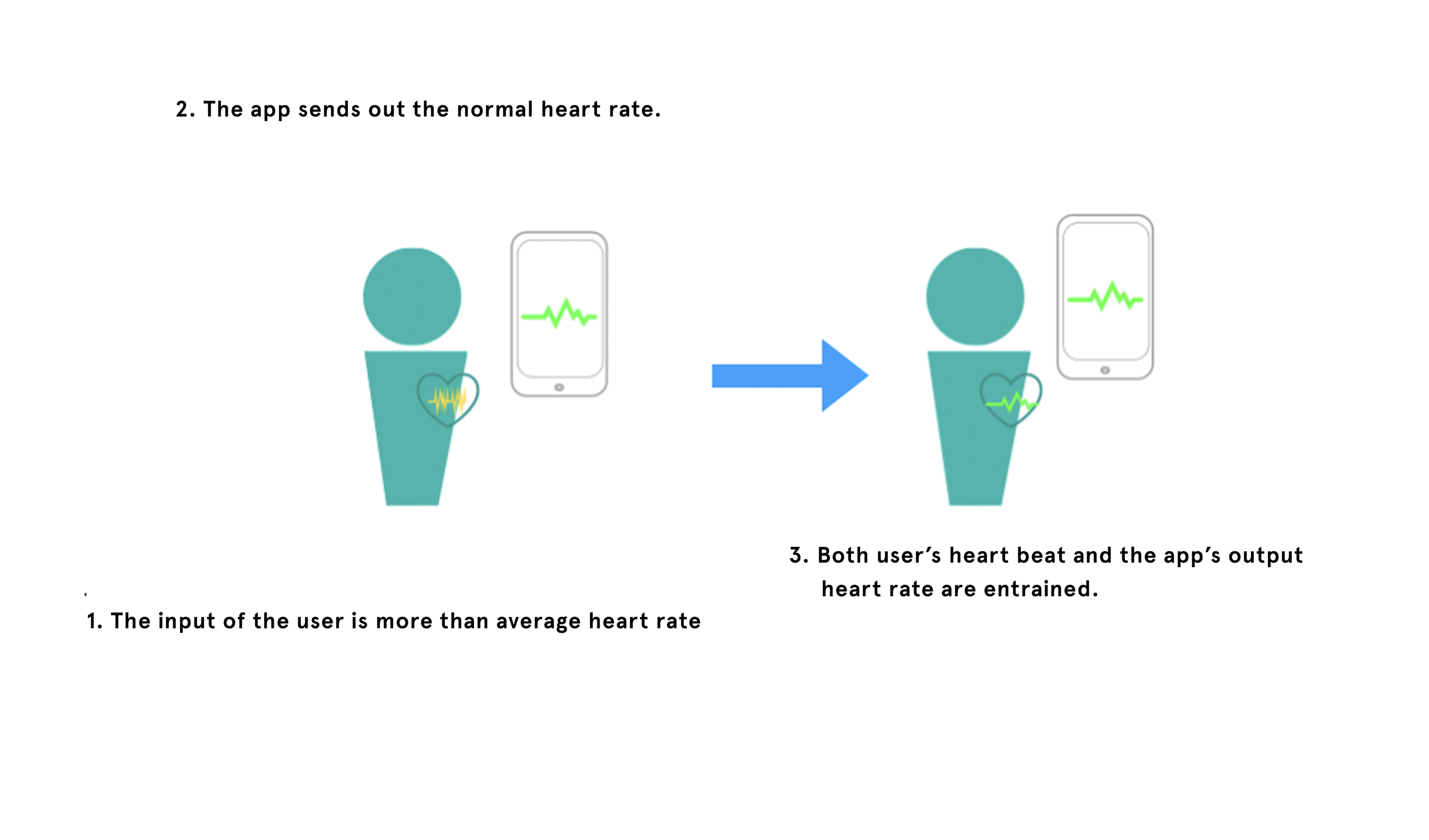

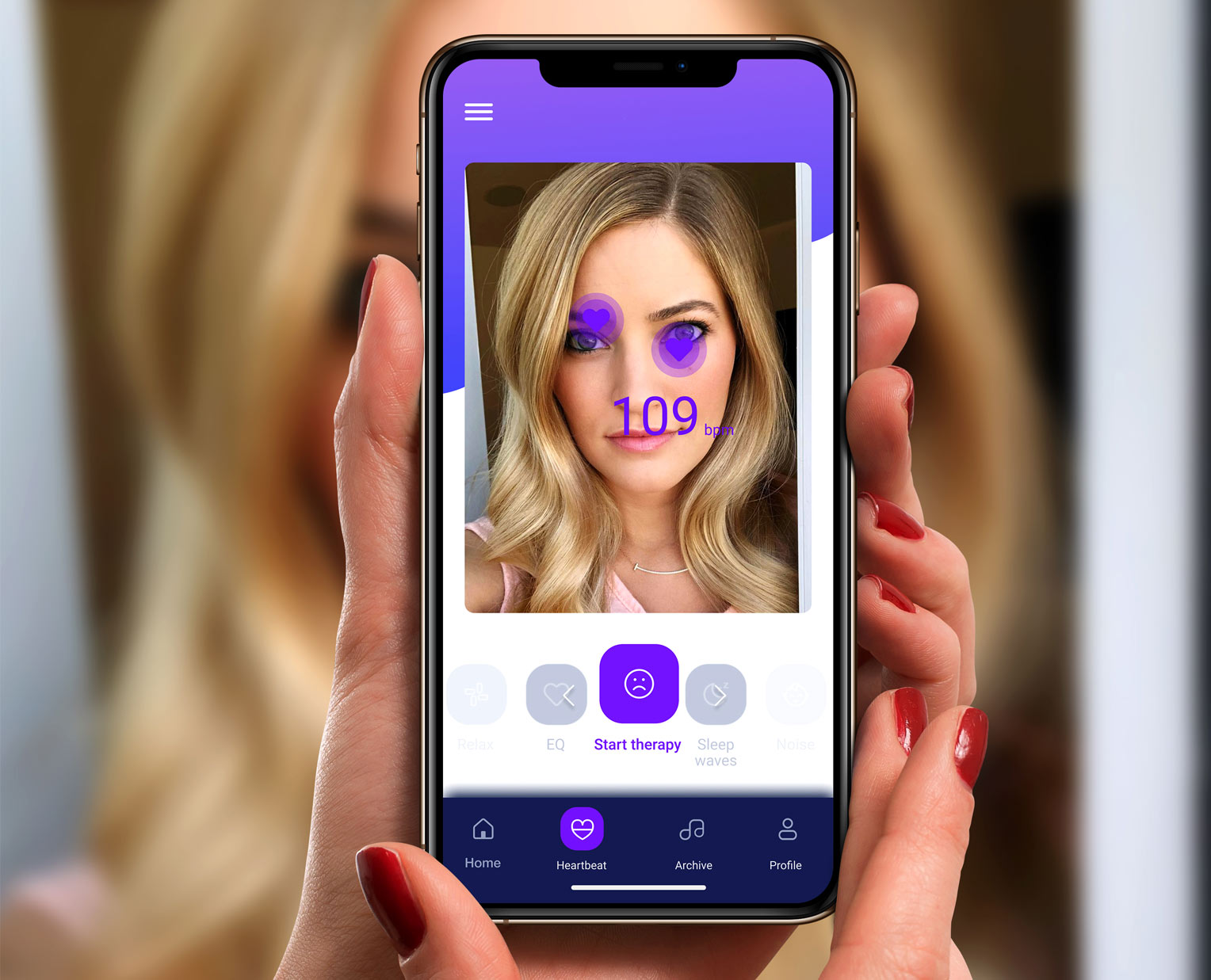

This is where Stress-less comes in as an audio environment and therapeutic device where users can tune into the desired pace and sounding heartbeats. The audio parameters will give the user control to manipulate the pace and certain qualities/characteristics of the audio. It first collects the heart rate from the user remotely with a video processing and plays back heartbeats at the rate according to the captured data. The pace gradually changes towards the desired (e.g., resting- or energized-state) heart rate. This is developed and aimed to be used as a therapeutic device privately and also with health professionals in their practice, preferably with full-range loudspeakers for more effective entrainment.

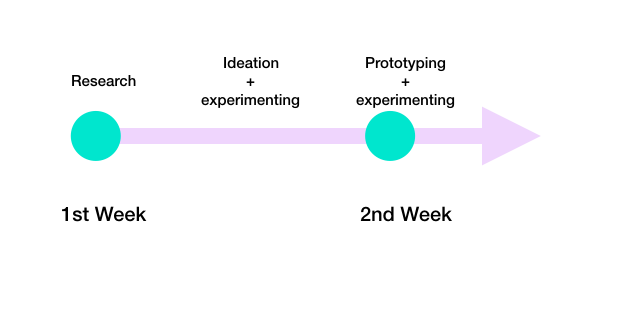

1.2 The timeline and overall plan

The workshop lasted for two weeks (Figure 1). We planned to spend the first week doing research on the topic (heart rate entrainment) and go through the ideation process (Figure 2) while running some basic experiments on Csound. Since everyone in this project was new to Csound, we planned to spend a decent amount of time understanding the basic elements (e.g., structure, syntax) of the language in the first week. With this limitation, we realised that we won’t have enough time to have our “dream program” fully working within two weeks. So by the end of the second week, we planned to have a basic prototype completed. Also, considering our background (a mixture of music technology and design) and limited amount of time, we decided to divide our work into segments depending on our expertise while taking up enough new audio programming challenges for everyone.

1.3 Concept development

We aimed to develop a program that can:

- Capture the user/patient’s heart rate

- Play simulated heartbeat at the captured rate

- The simulated heartbeat gradually (controllable) synchronises to the desired rate (controllable) over time

2. Key features in the prototype

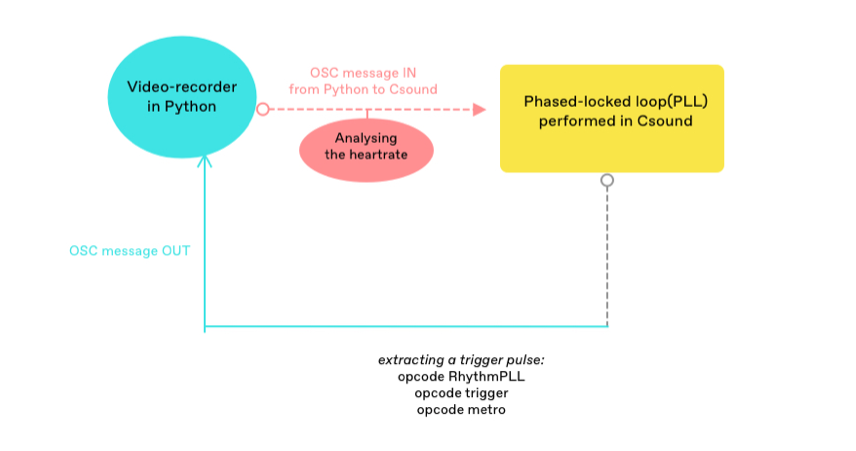

We used Csound and Python for our prototype. The two languages are connected via Open Sound Control (OSC). Here we discuss the key features, and also some of the challenges and solutions we dealt with during the two weeks.

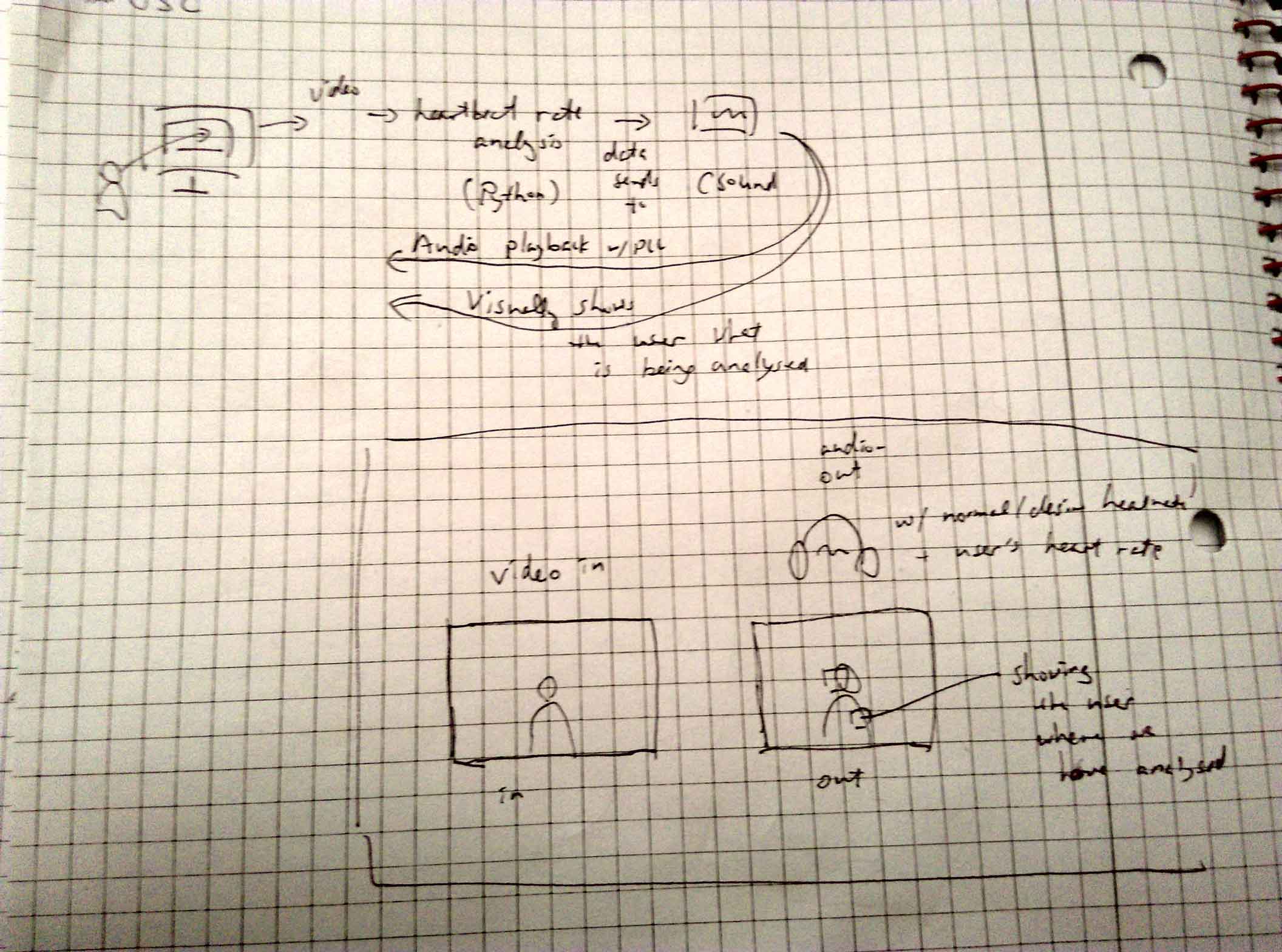

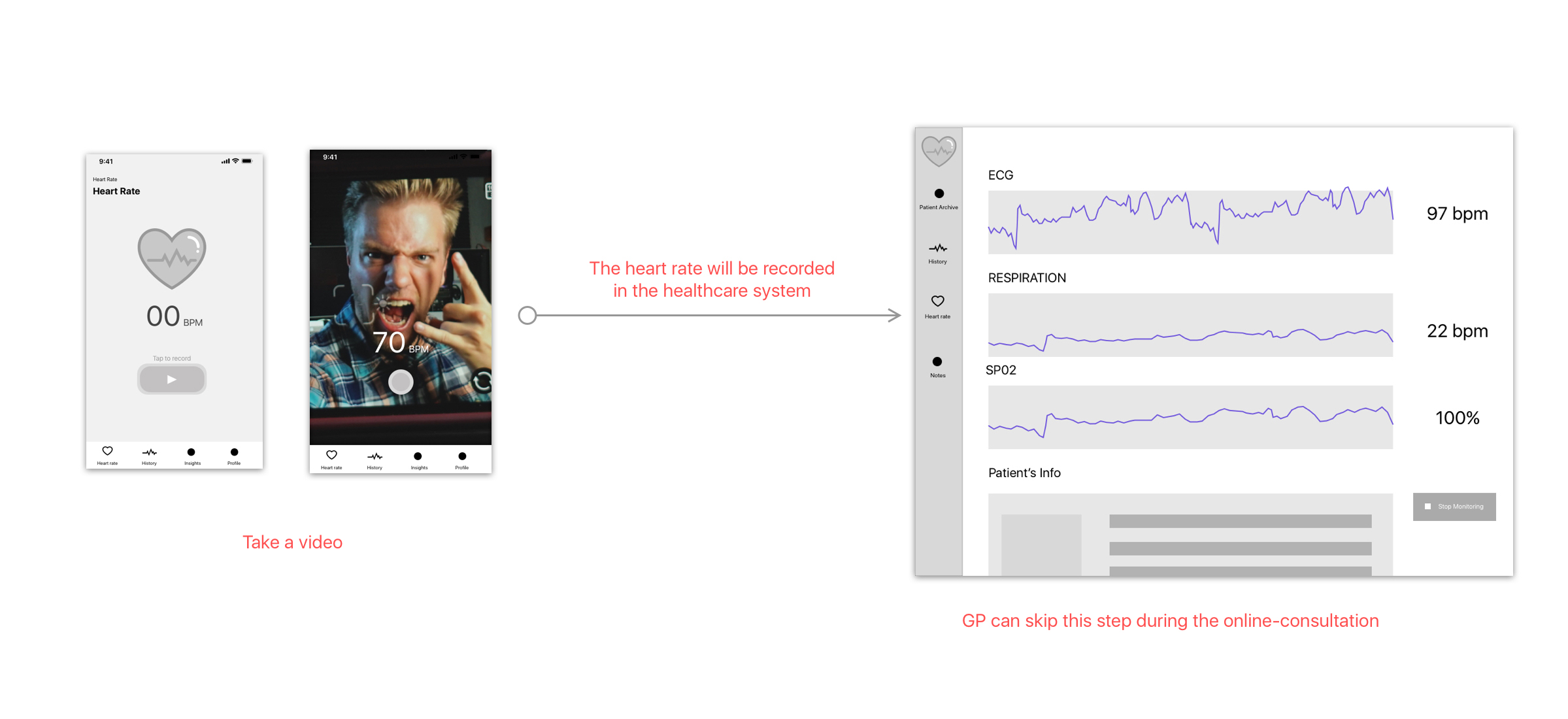

2.1 Capturing heart rate

As illustrated in Figure 3, we needed to be able to capture the user/patient’s heart rate. We have adapted the Eulerian video magnification (EVM) as our tool to capture heart rate remotely. EVM is a computational technique for visualising subtle colour and motion variations in ordinary videos by making the variations larger. EVM helps to detect small changes that are usually not possible to see with naked eye. Some of the other applications can be recovering sounds from detecting vibrations of objects in distance and characterise material properties. This technique can help to enhance digital healthcare experience for both patients and doctors. More information can be found on this website.

For our prototype, we have adapted EVM in Python. After analysing a video recording (.mov) of the user/patient’s face, EVM outputs a heart rate (in BPM). This value is then sent to Csound via OSC.

2.2 Phase-locked loop (PLL)

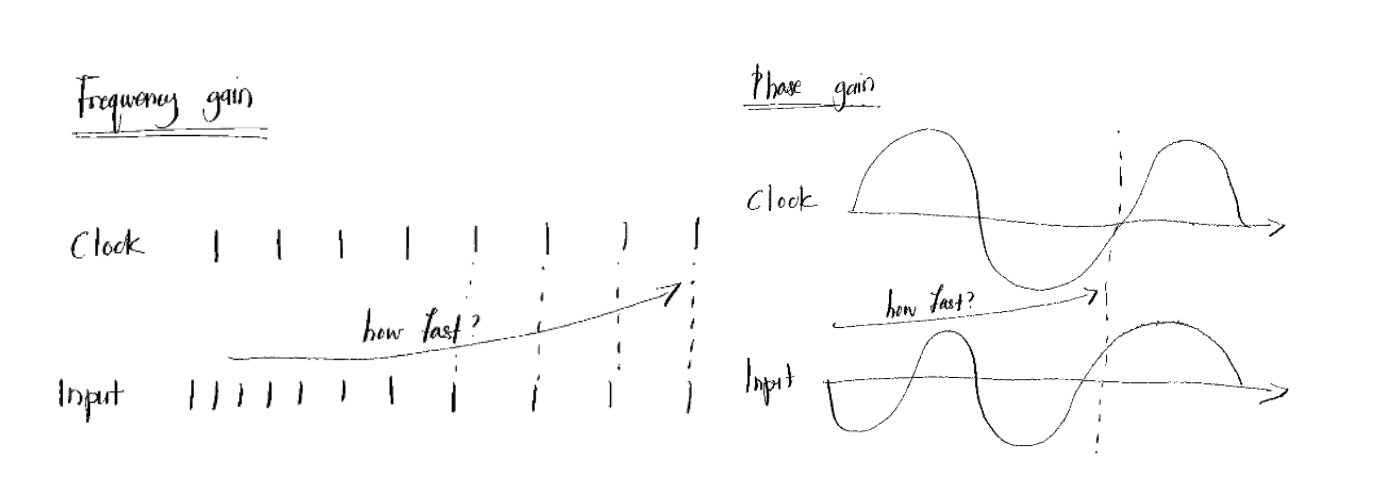

PLL is used as our control system in Csound (Opcode) where the synchronisation processing takes place. PLL user defined opcode in our case takes a clock pulse, initial frequency, frequency adjust gain, and phase adjust gain as inputs. By adjusting the frequency and phase adjust gains, we could control how slow or fast it takes until the input pulse is synchronised with the clock (Figure 5).

4. The prototype demonstration

5. Sonification

In order to synthesize a heartbeat sound, we needed to understand some of the basic acoustic characteristics of real heartbeat sound. This was an important step as we wanted to create a sound that resembles a real heart.

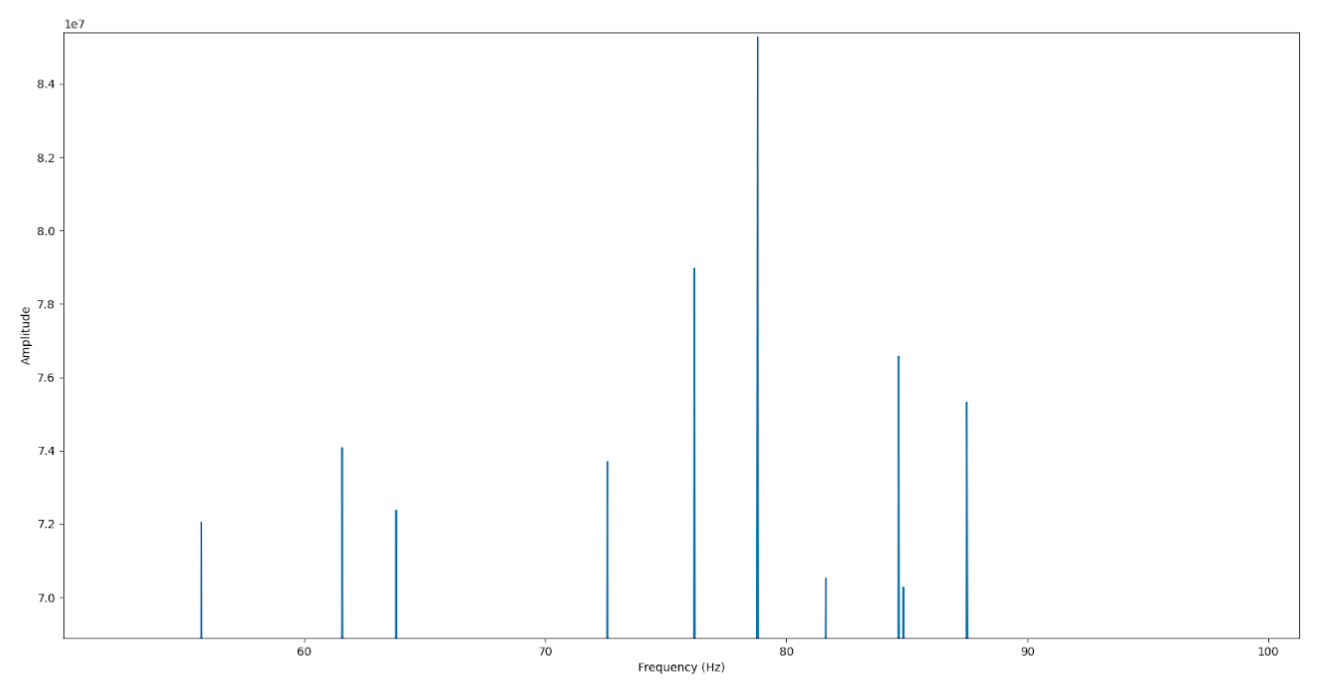

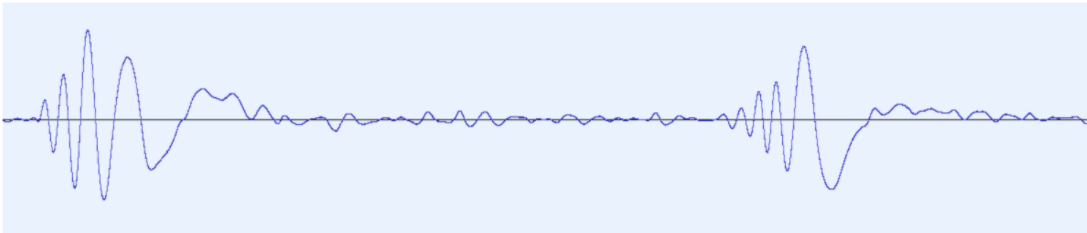

The first step we took was to run Fourier Transform to find the fundamental frequency from our acoustic model. We concluded that the most important frequency content is around 75~85 Hz as illustrated in Figure 6.

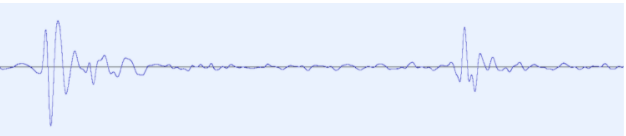

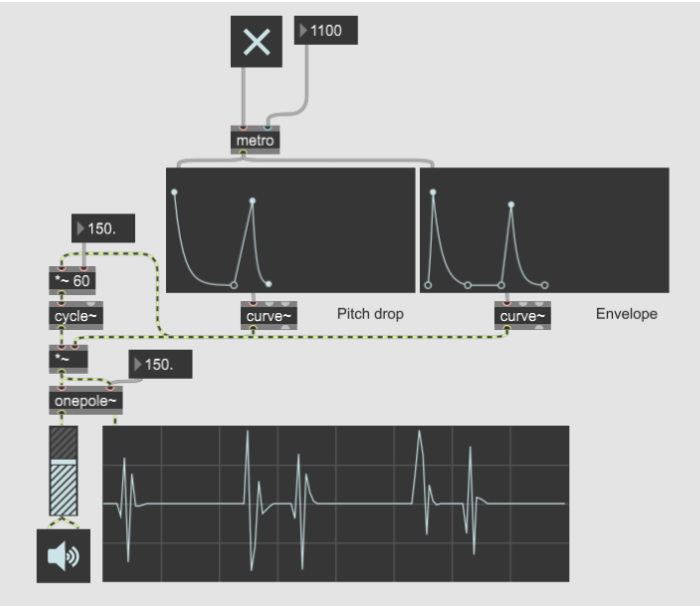

We then studied the envelope of our acoustic model (Figure 7). For the time being, we were able to imitate this on another audio programming language (MAX/MSP, Figure 8), as we needed more time to implement this in Csound, and created a demo.

The result of the demo (Figure 9) resembles the real heartbeat to some extent, but there is more work to be done (e.g., the attack time of the second pulse) in the future to sculpt the sound.

6. Reflection

Dongho:

Considering we were very new to Csound, we have made great progress within the given time frame. We managed to develop a working prototype using a new language! This prototype will be a good foundation and model to develop the program further in the future. More in depth understanding of the core features of the prototype will help the future development which will require more time and effort.

It would have been great to spend more time on examining the acoustic sound quality and characteristics of real heartbeat sounds. The direction we took (FFT and qualitative envelope analysis) and its result seems like it’s a good starting point. Perhaps, there is a room for other musical features in the future development than only imitating the real heartbeat sound. This should be explored and experimented further.

Although there is disagreement among in the current literature whether or not acoustic stimulus has an impact on heart rate entrainment, there seems to be a great research opportunity. As mentioned earlier, more range of controllable stimuli should be explored. Also, there seems to be an opportunity for development of a therapeutic device for private use and healthcare environments.

Joni:

With the limited time, we were able to capture the heart rate using video analysis in Python and perform synchronisation through PLL in Csound. What we have established in this workshop has given us a good starting point to develop our app idea in the future (Figure 9). The heart rate synchronised technology will have more features, such as allowing users to change the EQ and set the standard heart rate of their own. Additional features include suitable mindfulness music or soundscapes to users whenever their heart rate is detected as faster than average.

Furthermore, the aesthetic aspects of the heartbeat sound could be better and that we could add more layers. In our app idea, it is designed for users who can keep track of their heartbeat by taking a video.

Finally, in the past two weeks, I have learned a lot and my brain fried in a good way. Now, I am able to interpret and modify codes more efficiently and gain understanding of the fundamentals of digital audio signal processing.

7. Our vision

In our future vision of this project, this idea of using video heart rate analysis technique can be implemented in online GP consultation, so that the patients and doctors do not need to necessarily meet physically. It can reduce a lot of time spent in the whole travelling journey from home to the doctors. In addition, with an on-going pandemic, and economic downturn, we believe that this idea can accelerate the evolution of healthcare ecosystems. As we move forward, organisations can consider ways to use healthcare ecosystems to improve patient experience and health, while reducing total costs.

References

Hong, C., Hsiao, W., Wang, H., Huang, S., Shao, K., Luo, S., Chiu, W., Lee, Y., Hou, M. C., Chao, S., Tseng, C., & Chen, W. (2011). The Sustained Exhilarating Cardiac Responses after Listening to the Very Fast and Complex Rhythm. 2011 Second International Conference on Innovations in Bio-Inspired Computing and Applications, 53–56. https://doi.org/10.1109/IBICA.2011.18

Ivanov, P., Ma, Q., & Bartsch, R. (2009). Maternal-fetal heart beat phase synchronization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106, 13641–13642. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0906987106

Mütze, H., Kopiez, R., & Wolf, A. (2018). The effect of a rhythmic pulse on the heart rate: Little evidence for rhythmical ‘entrainment’ and ‘synchronization.’ Musicae Scientiae, 24, 102986491881780. https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864918817805

Ribatti, D. (2009). William Harvey and the discovery of the circulation of the blood. Journal of Angiogenesis Research, 1, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/2040-2384-1-3

Saperston, B. M. (1993). Method for influencing physiological processes through physiologically interactive stimuli (Patent No. 5267942). https://www.freepatentsonline.com/5267942.pdf

The History of the Heart. (n.d.). Retrieved February 19, 2021, from https://web.stanford.edu/class/history13/earlysciencelab/body/heartpages/heart.html