Strumming through space and OSC

OSC Guitar

My second project for the audio programming course was to accurately simulate a guitar strum in Puredata using the sensor information sent from a mobile device in motion. I wanted its interaction to be reflective of the direction, speed, and acoustic uniqueness of a real guitar strum. By uniqueness I mean the qualities of a strum that are not necessarily intended by the musician, like the intensity of each string strike and the delay between each individual string as the fingers (or pick) slide across the strings. These additions make both the sound and the experience of strumming quite realistic and, as implemented in this patch, benefit the realism of the virtual strum. However, a number of unforeseen difficulties made the feat of a seamless gesture-to-sound production quite a challenge. As I will discuss, one of the greatest barriers to responsiveness was network latency and the inability for native-local interfacing within both Puredata and sensor data on my mobile device.

Strings and Things

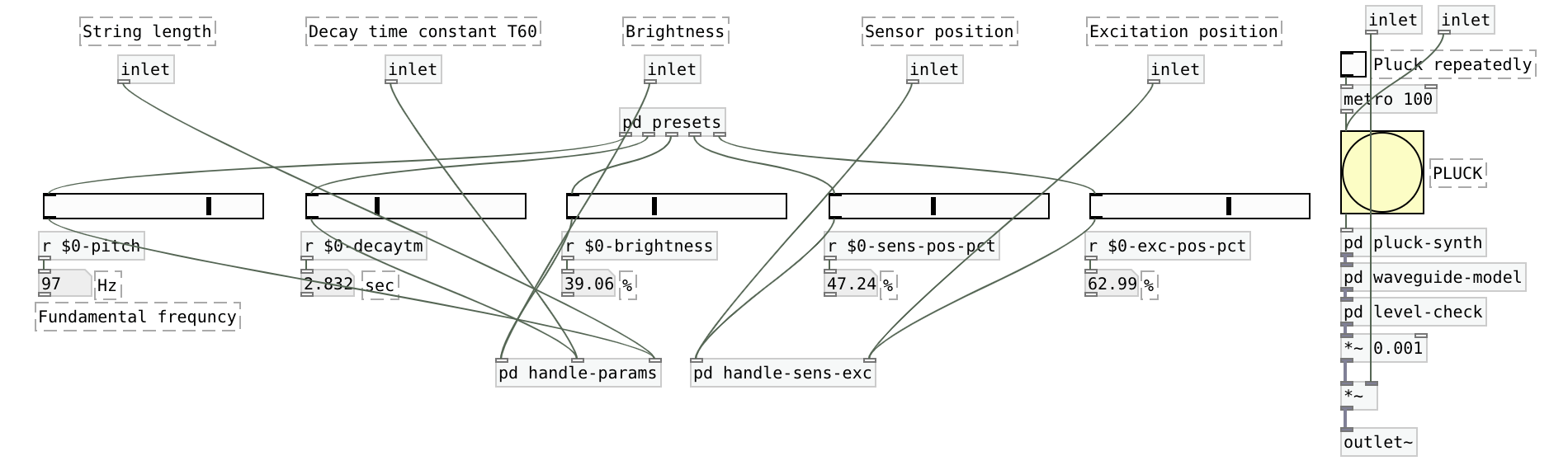

I began the project with a detailed search for an accurate model of a string. While I could have built a simple string, the focus of my work was integrating the string model into a framework from which it could serve as a guitar. The string was built using a digital waveguide model by Edgar J. Berdahl and Julius O. Smith. Their model is quite good, both to the ear and to the standards of Stanford’s Department of Music.

However, the model was not designed in a way to be used in polyphony. To correct their design, I renamed each array, send, and receive to be unique for each instance of the waveguide model using a prefix of “$0-”. This allowed each object to be instantiated with a unique identity and as a result, enabled the messages passed by each of the six strings to exist without overwriting potential shared arrays or variables. I also reformatted some of their code to better fit my purposes like adding inlets and outlets that would communicate with the main patch and the six strings in concert. I also cleaned and reorganized their layouts to make more functional sense.

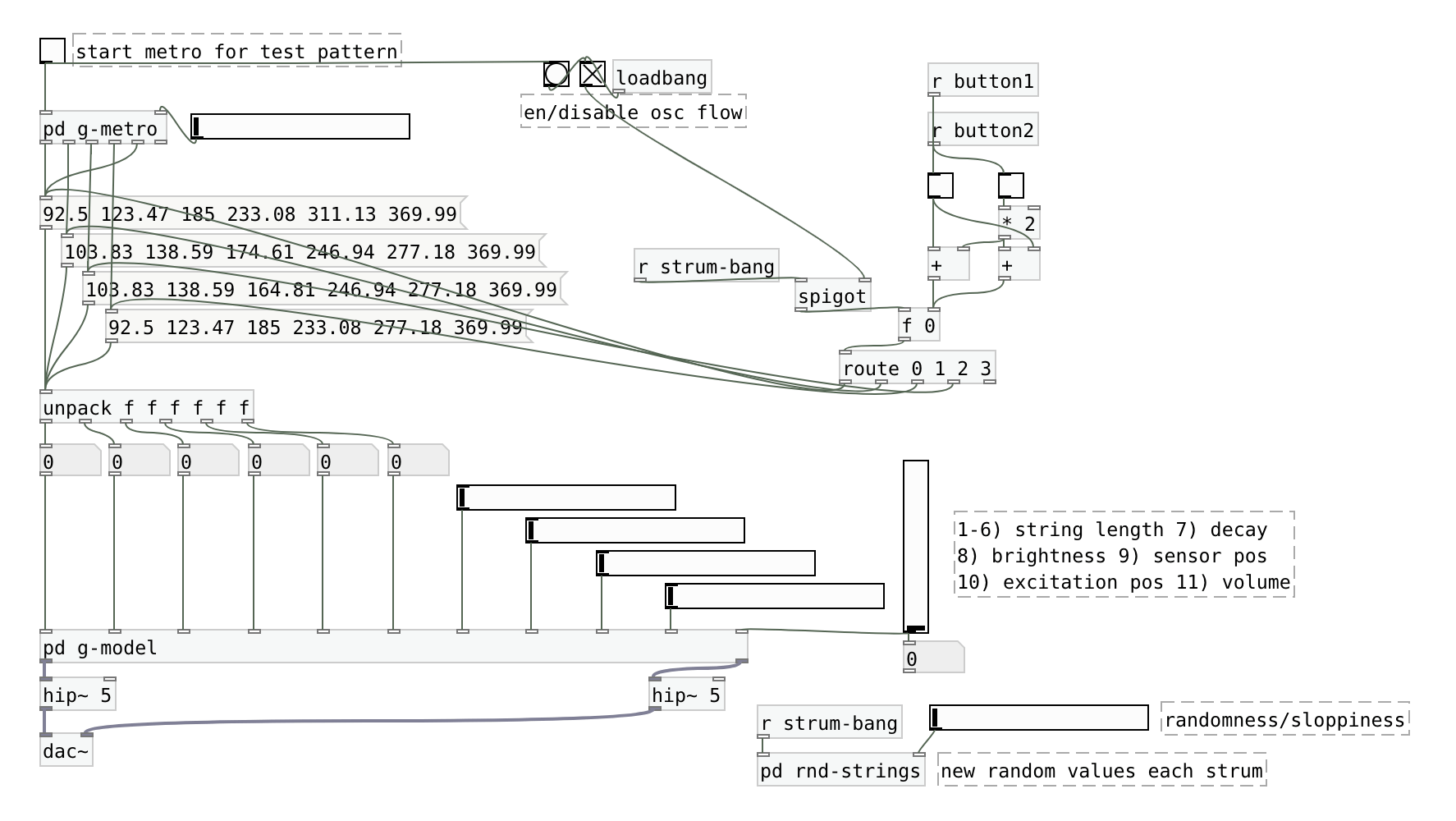

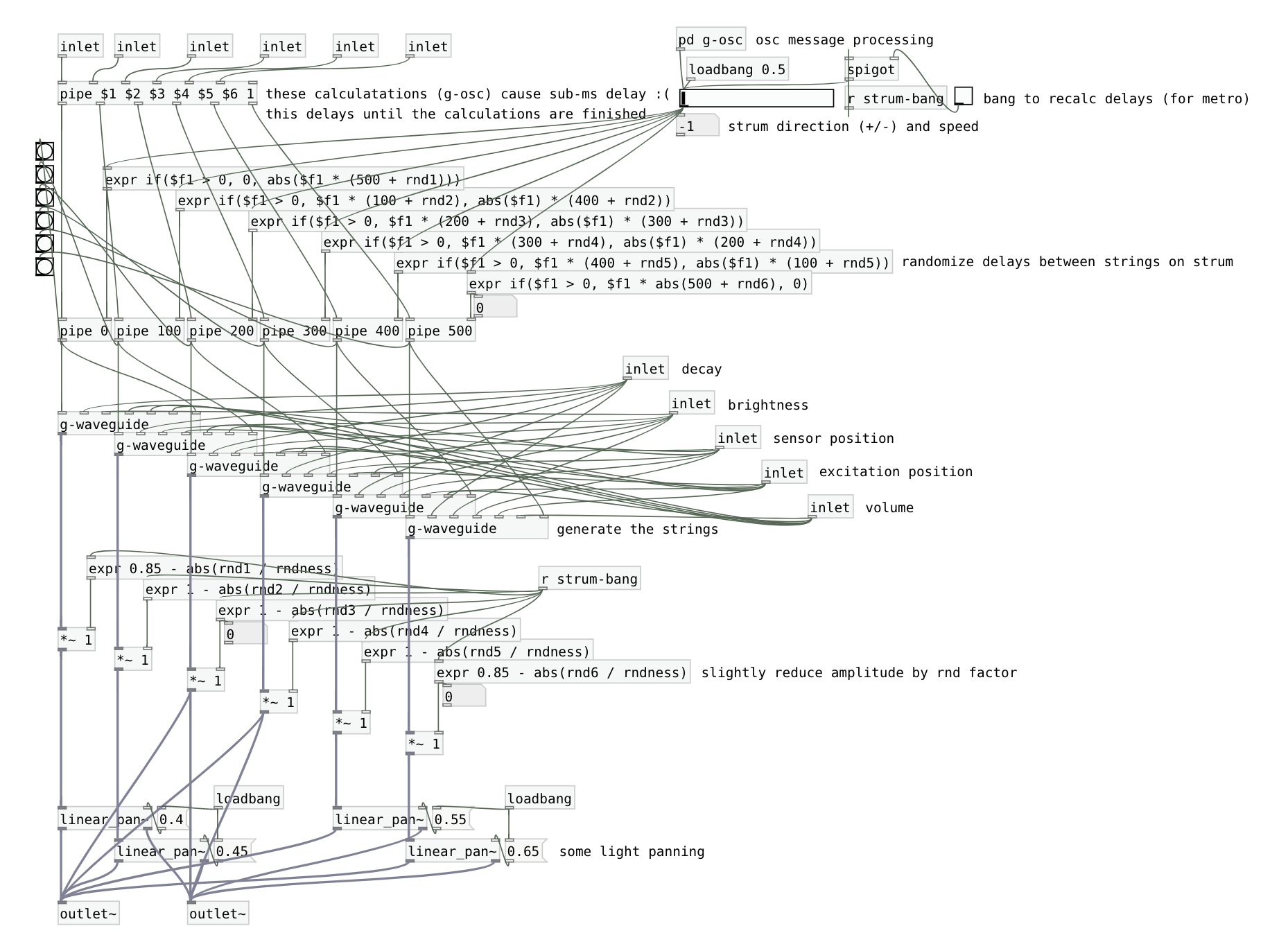

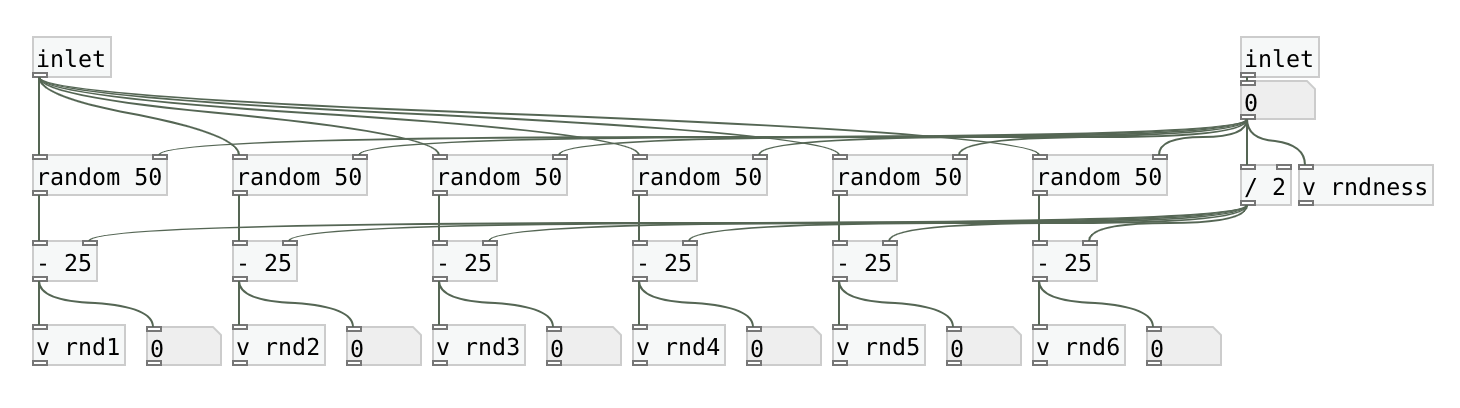

Once the strings were in place, I assigned the fundamental frequency of each string of four chords to four messages and made a simple metronome to send a chord pattern to play the chords (for a non-interactive demo). To create a delay between each string I used the “pipe” object prior to reaching the waveguide model. The delays’ right-hand argument allows for an input number, whose sign (positive of negative) determines whether the string delays will cascade downwards or upwards. The expression also considers randomness by calling six variables that were assigned six random numbers included in the sub-patch “rnd-strings”.

These random variables are created on every “strum-bang”, a global variable used to send a bang when there is a strum (either from the metro or OSC). The random variables in the delay increase or decrease the total delay time (and is then factored by the acceleration of the strum). After the audio signals are generated, they have their amplitude reduced by the same random factors used before. There is then some light panning that pans the mono signals of the top two and bottom two strings. This is finally sent to the dac.

The Notorious OSC

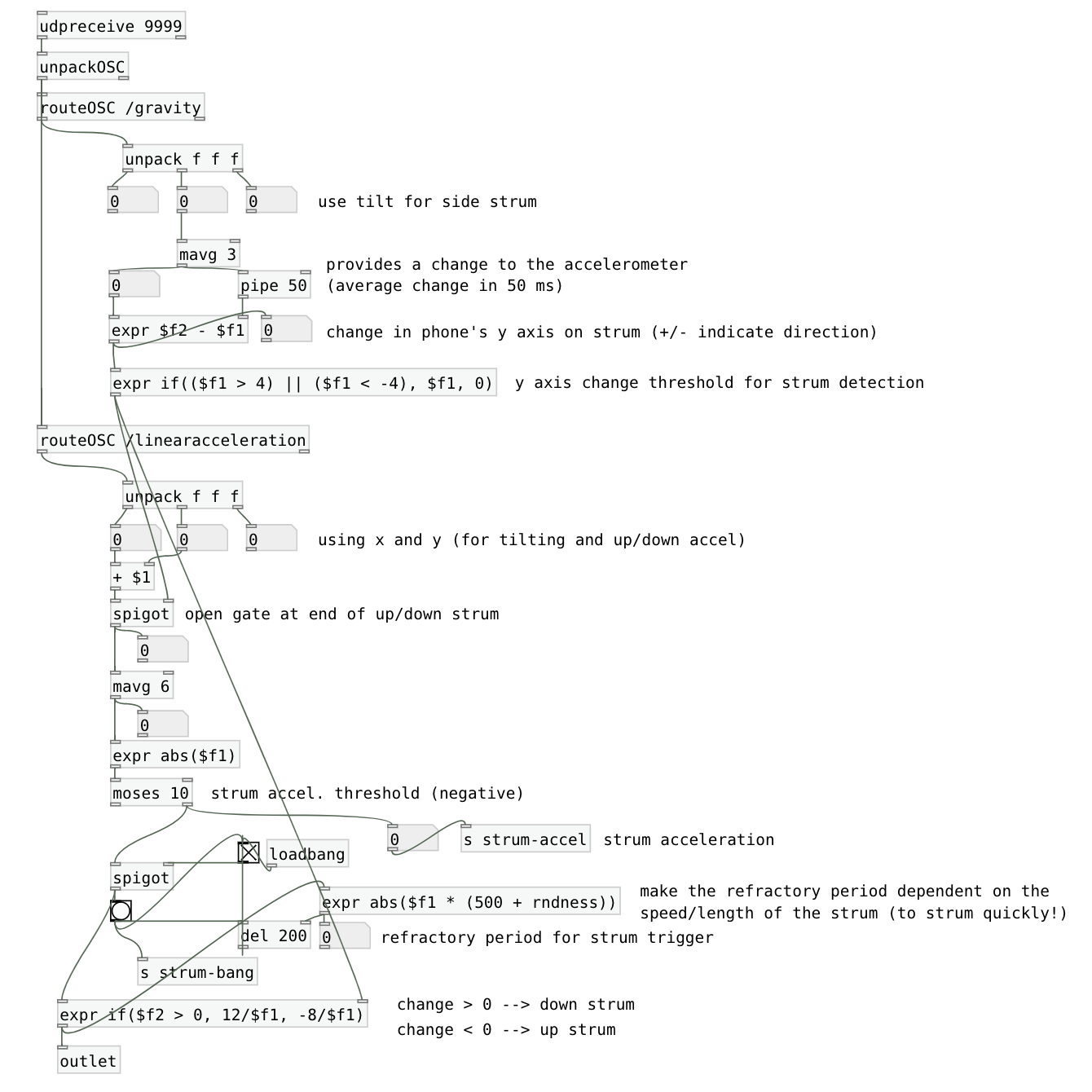

The last step was into employ a method to send OSC messages from my smartphone’s accelerometer. I used the Android app Sensors2OSC to send OSC messages from the gravity and linear acceleration sensors in the phone. The “mrpeach” external library facilitated receiving these messages into the patch. I chose the gravity sensor over the accelerometer sensor because the tilt values that correspond to rotating the top of the phone downwards and upwards were distinctly positive and negative as the top the crossed over the y-axis (horizon).

Two mechanisms were created to trigger a bang from a strum using the phone. The first opens or closs a gate depending on whether or not there is a sufficient change in the tilt of the top of the phone from the gravity sensor. The second mechanism determines if the acceleration of the strum is enough to trigger a bang. In its design, the second impulse generator can only be activated if there is enough of a properly shaped strum gesture. In addition to the thresholds preventing any rapid activation, I also created a refractory period that prevents a bang from being sent until the previous strum has completed from calculating strum duration. The impulse that is sent when a strum makes it through the thresholds is a positive value from the linear acceleration. The sign of this number is then changed depending on whether the strum was down or up (using the sign of the gravity sensor’s change). This number determines the speed and direction of the strum. If all thresholds were tuned perfectly and there was zero latency (my next point), this would allow rapid strumming of the virtual guitar.

Complications

Unfortunately, one of the first issues I recognized was the latency that appeared from communicating over the local network. The latency was also inconsistent as well as the message rate that was being received (not to mention messages dropped). There were some moments where the speed and response of the OSC messages was incredibly fast and at other times inoperably slow. Because of this, a good portion of my time was spent finding threshold values and averages that catered to the message rate and latency. There is also the issue of this configuration being device dependent. Different smartphones will likely have different sensor hardware, sensor names, ranges, rates, etc. so this patch is certain to need some configuring in each case. The initial goal of this project was to build the app in Pd and afterwards “simply and easily” port it over to the MobMuPlat application for Android and iOS. However, this app does not appear to read the necessary sensor data natively and there do not appear to be alternatives in hosting Pd patches on Android. For the time being, this patch will have to be hosted on a remote computer and receive OSC messages from a device connected to the same network.

The audio within the video was recorded internally (oddly the pops only appeared after video editing - my computer was struggling with that fabulous transition).

All in all, this project was a great introduction to Puredata and definitely taught us the general principles of the language as well as some of the challenges you only encounter in hour 11 of debugging. While making this a standalone app would require a bit more investigation into MobMuPlat or some other Pd host-able interface, I think my goals were met. And when the network connection is good and the thresholds are polished, it’s quite surprising how responsive a network connection can be.

My project’s code can be found here.

Works Cited

Iglesia, Daniel. Monkeyswarm/MobMuPlat. 2013. 2020. GitHub, https://github.com/monkeyswarm/MobMuPlat.

MobMuPlat - Mobile Music Platform. http://danieliglesia.com/mobmuplat/. Accessed 7 Feb. 2020.

Plucked String Digital Waveguide Model. https://ccrma.stanford.edu/realsimple/waveguideintro/. Accessed 7 Feb. 2020.

SensorApps/Sensors2OSC. 2014. SensorApps, 2020. GitHub, https://github.com/SensorApps/Sensors2OSC.

Sensors2OSC - Sensors2. https://sensors2.org/osc/. Accessed 7 Feb. 2020.