A generic overview to the 'Sound in Space' exhibition at KIT

Marking the final event before Easter and from our Sonification and Sound design course I was tasked to visit the group exhibition ‘Sound in Space’ that took place on the 11th of April at Gallery KIT, Trondheim. It was also the closing event for the sound art course in which music technology and fine art academy students (NTNU) could participate. Beside the exhibition there have been also screenings, concerts and happenings. Among the performers were Ellen Lindqvist, Jeremy Welsh, Tijs Ham/Craig, Øyvind Brandtsegg and Michael Duch. It was a a nice afternoon with many events going on and things to explore, however I will introduce just two installations that were created under the umbrella of ‘sonification and interactivity’.

Playful sonification: Interactive and complicit

Beforehand all students had a short workshop on physical computing. Within a few days they prepared different interactive installations. Some participants had never seen an Arduino before nor had any programming experience. Others collected everything they had been doing so far into their work as Øyvind Brandsegg and Daniel Formo told me (teachers). The first part of the sound art course would work with field recordings, composing stories in sound with environmental sounds, which would go hand in hand with the digital composition course, having audio processing techniques and algorithmic composition. With Arduino again they could quickly protoype their ideas. The sonification process again should reveal itself through a creative access and control of the installation pieces with sensors or other activation tools. The context of interactive sound art can challenge new experiences with music and knowledge also for non-experts:

“[W]orking with sound is an active multisensory experience which bridges the gap between perception and action. Sound making is considered to be a meaningful aesthetic experience not only for musicians but also for users who do not posses expert musical skills. This shift from reception-based to performance-based experience brings new challenges to sound design and sonification practices. .” (Hermann, Hunt, Neuhoff)

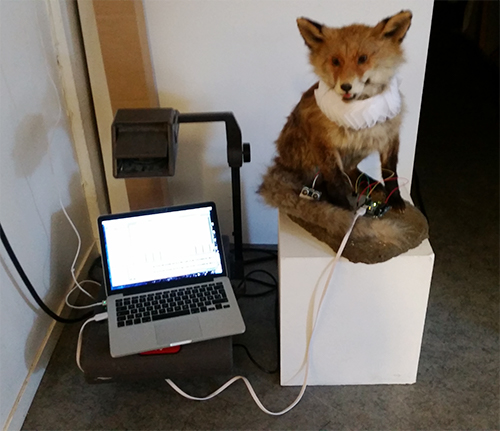

Most of the items in the sound art exhibition were indeed so designed that the visitors could directly engage with the interactive installations. The talking fox above in the first figure was made by Mina Paasche, a student from the fine art academy. A proximity sensor established the interactive part, when approaching to the fox he would start talking to you and the closer you get the more distinct the sample would get. Too bad I couldn’t get a hold of her so she could have might explained to me what the fox was actually preaching.

Aspects on sound art

What is sound art though? There is no specific definition out there since it is produced by different actors from different disciplines like visual art, composition, sculpturing just to name a few. With digital technology sound art has undergone transformations, especially through the low threshold accessibility of sound tools. Often features overlap with ‘electronic art’ e.g the use of technology. Like a visual artwork sound art has no specified timeline; it can be experienced over a long or short period of time, without missing the beginning, middle or end (Alan Licht), as sound is visceral and emotive it can define a space at the same time as it triggers a memory (Susan Philipsz).

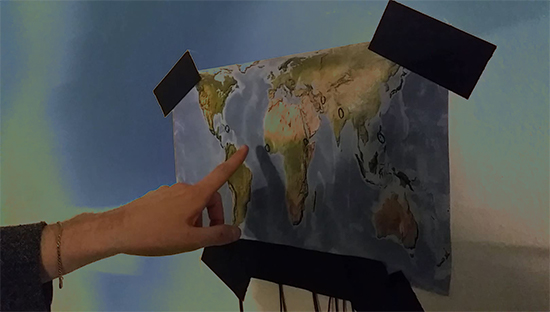

One of the students I met there was Joel Hynsjö (MuTek). Joel’s ‘Do you remember’ (see below) actually plays with that sense of memory and space in a very practical way. He collected speech in news reports from the worst natural disasters world wide in the last 6 years. On a world map one could see six circles in different regions, the piece is silent until one of the circles is being pushed. There is a voice which interrupts randomly the news-reports, every time you push there is a chance that “do you remember” is played instead of the report.

The idea he explains evolved from thinking about an interactive method to recall weather reports but gradually moved into some other sort of information transmission. ‘I just wanted some kind of interface that wouldn’t be that technical, basically it is just a paper with rings on it and I liked that. Together with the noise-cancelling headphones I wanted to create an intimate moment within the noisy environment where one could get more introverted as the reports are getting quite close to you.’ The rings on the paper lying on top of 6 pressure sensors which are connected to an Arduino board. The Arduino sends messages to Max/Msp if a sensor gets pressed which then triggers the radio samples. Joel had some programming experience from the first semester in Max/Msp but most of the workshop days he spent learning how the Arduino works.

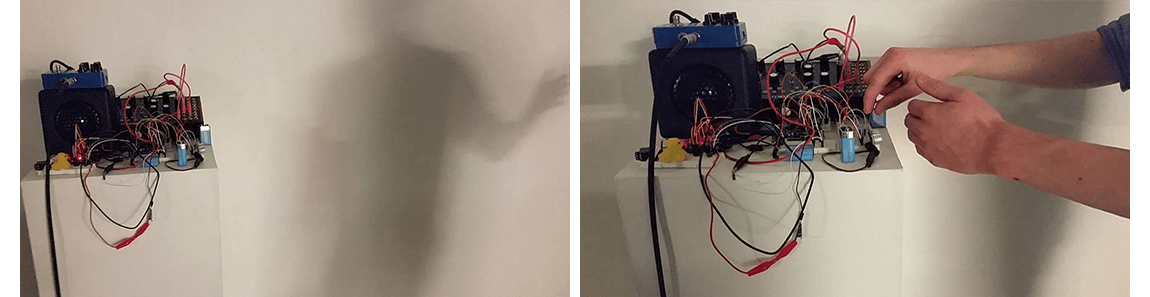

Another student I met was Emiel Huijs. He developed an ultrasonic distant sensor that controls different musical parameters. A pressure sensor for LFO grain modulation and a little duck gave it an interesting twist. Listen here:

Reflections

It seems to be good practice to explore sonification by physical computing. The development of an instrument that works with playful and interactive functions looks like a rewarding and entertaining way to learn and take up the subject. It is also committed to understanding each step during prototyping. But it also allows us to experience and reflect on how we normally interact with computers. In the context of art it also has the possibility to be not only useful, but also meaningful. At the same time, the useful skills that are developed can later be integrated into a variety of contexts. Interactive sound art installation are a great opportunity to invite non-experts exploring the matter playfully.

References

Hermann, T., Hunt, A., & Neuhoff, J. G. (2011). The Sonification Handbook (1st ed.). Berlin: Logos Publishing House. Retrieved from: https://sonification.de/handbook/.

Alan Licht: Sound Art - Origins, development and ambiguities

Susan Philipsz, citation retrieved 30.04.2019 https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/s/sound-art