Designing DFA and LAA Network Music Performances

Two Configurations for Network Music Performances in High Latency Environments

Much time, effort and research in the field of NMPs goes into the reduction of latency. For seamless musical performances over a network, latency needs to be imperceptible to musicians. Due to the nature of many remote solutions, especially those available at a consumer level, this is often not possible and latency can be at levels making synchronised music performance unworkable.

In their paper linked below, Alexander Carôt and Christian Werner propose several configurations for working with situations where latency is unavoidably high. These revolve around, rather than attempting to reduce latency, to accept its presence and potentially use it to form part of the music or synchronisation. These are often based on one location being termed the “master” for the sake synchronisation, with the second being the “slave”. Here we will instead use the terms primary and secondary nodes to denote this. Our groups attempted to implement the following two configurations for musical performance:

Delayed Feedback Approach involves delaying the primary node’s signal relevant to the roundtrip latency as to sound the same as how the secondary node will experience it.

Latency Accepting Approach revolves around not attempting to improve or optimise latency in any way and instead absorb it into the creative content of the performance.

Delayed Feedback Approach (DFA)

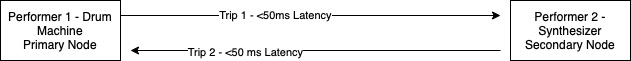

For this designed performance we used a drum machine at the primary node playing sequenced drum patterns and a synthesizer at the secondary node played by a human musician.

The design of this configuration was that the drum machine would be transmitted across the network in its latency-rich state to the secondary node. The performer at the secondary node would play along with the drum machine, transmitting the output from the synthesizer back to the primary node, again with unaffected high latency.

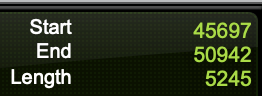

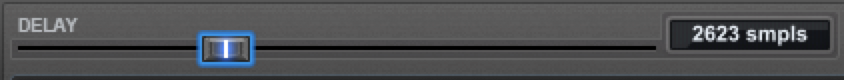

With the synthesizer signal being returned to the primary with latency, we added a sample delay to the monitor path of the drum machine which was equal to half of to the total latency in the system. As such, as the synthesizer was only travelling one way across the network, when the secondary node’s signal and the delayed drum machine monitor signal played together, they sounded in time.

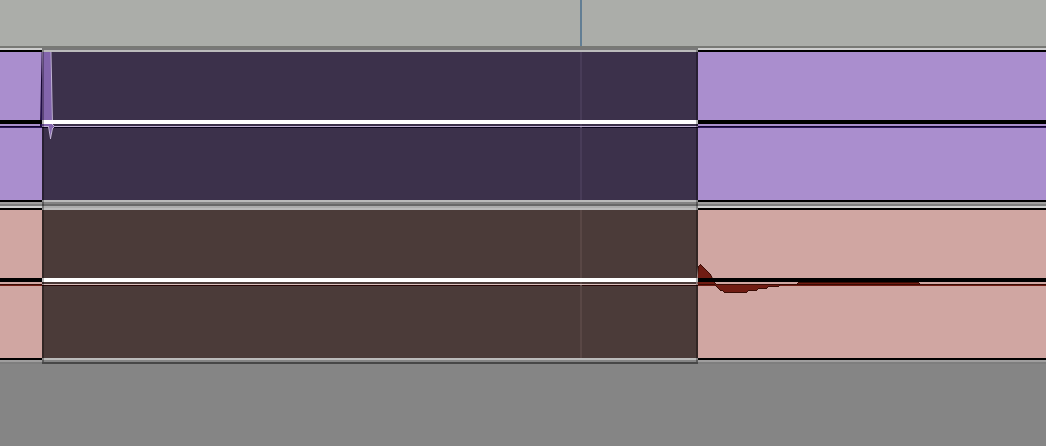

Here is the performance using the DFA configuration. The audio is recorded from the mixer at the primary node with a mix of the returned synthesizer signal and the delayed drum machine monitor signal. As you can hopefully see, this audio lines up perfectly with the footage from the secondary node, implying that the delayed monitor path was configured correctly.

Latency Accepting Approach

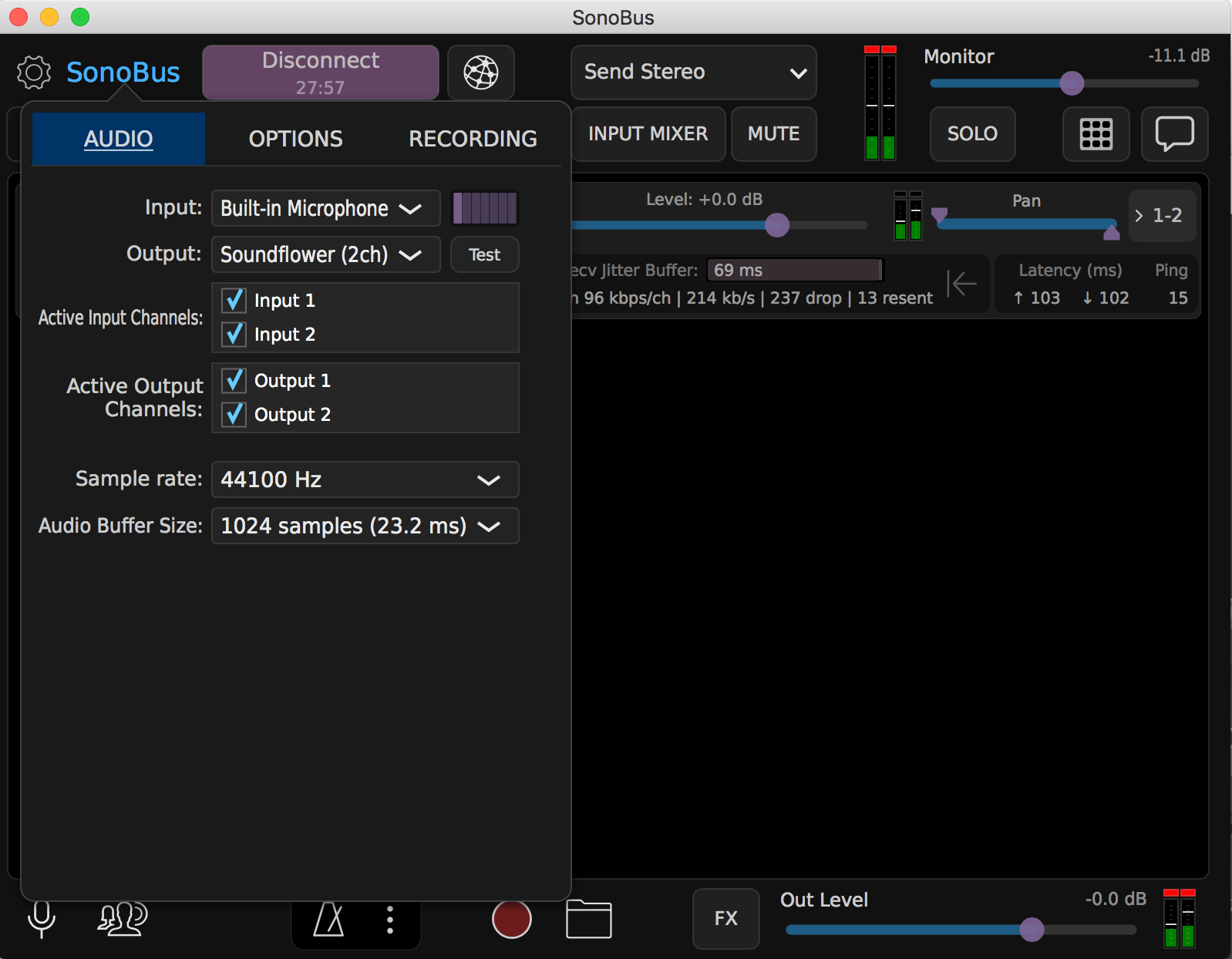

For the LAA (Latency Accepting Approach) Fabian and Henrik used SonoBus over a wifi connection to create a latency-rich environment. Roundtrip latency averaged at just above 200ms, giving a good foundation to try LAA.

As noted by Carôt and Werner, a latency accepting approach, lends itself best to ambient music with slow movements giving performers time to react to each other. As such, this is what was attempted here. A video of the performance is below:

Conclusion

DFA and LAA lend themselves well to different forms of telematic musiking in latency-rich environments. The more percussive music style was appropriate for the DFA while LAA was better suited to a beatless ambient approach.

For the DFA performance, while this approach worked well with the use of the drum machine, the monitoring delay would have made live playing difficult. This approach would be more feasible if all participants were playing to a ‘delayed feedback’ metronome, allowing all participants to, in effect, play to a single, synchronised timing source.

In practice, despite very high latency and having a lot of audio packet drops, LAA felt fairly seamless for the performers to play ambient music. We did not attempt to play rhythmically-based music with this approach as the high-latency would have rendered it impractical.

While neither of these approaches represent a generally applicable solution, they do offer technical and creative routes to allow for effect music performance in latency-rich environments. While DFA represents a route for more conventional, rhythmic music, LAA forces the musicians to work in an unconventional manner. This has the potential to open them up to greater creativity and different, new modes to work within its limitations.

References

[1] A. Carôt and C. Werner, ‘Fundamentals and principles of musical telepresence’, Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts, pp. 26–37, Jan. 2009, doi: 10.7559/CITARJ.V1I1.6.