Mastering Latency

Introduction

The Internet is widely used for audio communication. Numerous collaboration applications exist that make it trivial to have a conversation with almost anyone, anywhere. So, why is performing music any different? The problem is trying to keep a common rhythm between musicians in different locations. Maintaining a shared beat is difficult if it takes too long for one musician’s sound to reach another’s ears, and if this time (called latency) is too long (around 25ms [1]), it can make playing music together almost impossible. However, some techniques can be employed to work with latency, and not against it.

Goals/Plans

We decided to test two such techniques outlined by Alexander Carôt and Christian Werner [1] between the portal and the video room at UiO.

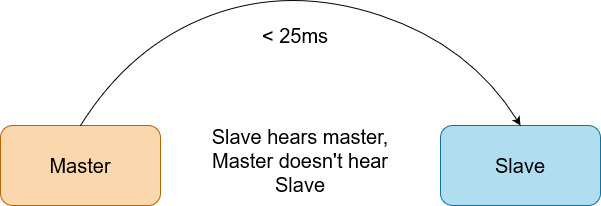

- Master Slave Approach (MSA)

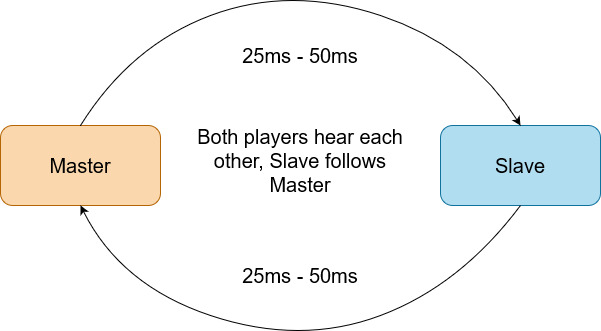

- Laid Back Approach (LBA)

These techniques are similar in principle. One player assumes the role of the “master”, determining the rhythmic elements of the performance. For the MSA, the master does not listen to the slave, allowing performances to take place at any amount of latency, whereas for the LBA both listen to each other and play with the latency adding a sense that the playing is relaxed, or laid back. The limit for this is around 50ms [1] before timing difficulties start to become noticeable.

We decided to perform in two constellations testing various latencies. For MSA, Hugh performed electric drums in the portal, taking the role of the master, while Kristian performed keys in the video room, playing various funk grooves. For LBA, Kristian took the role of the master, on keys, while Joachim performed saxophone, testing two jazz standards, the faster Donna Lee, and more moderate Solar.

Technical Specs

When playing music over the Internet sound passes through several stages, which all inevitably add latency [2].

- Geographical latency

- Internet service latency

- Home network latency

- Digital processing latency

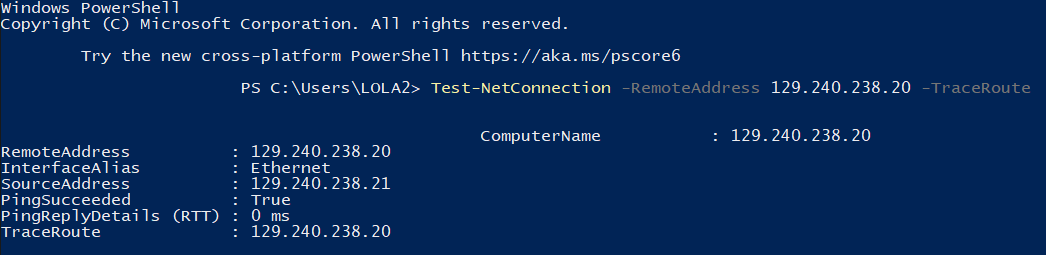

To be able to control for latency, we had to measure these first in order to ascertain a baseline. We measured the entire system and the network connection between the two UiO portals and found a total round-trip time (RTT) of 20ms.

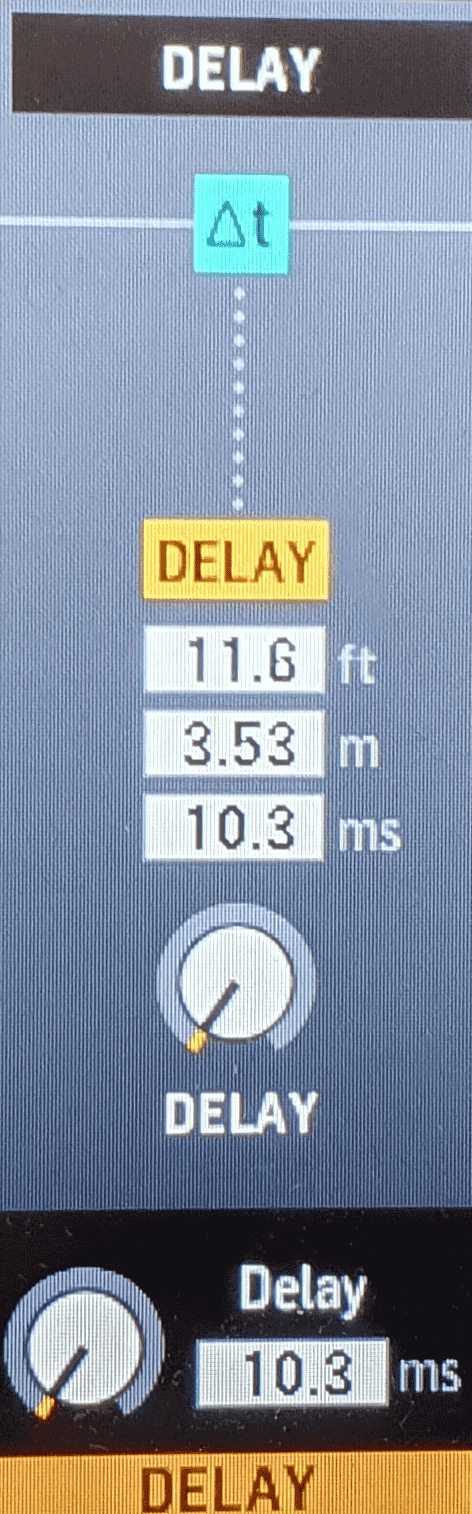

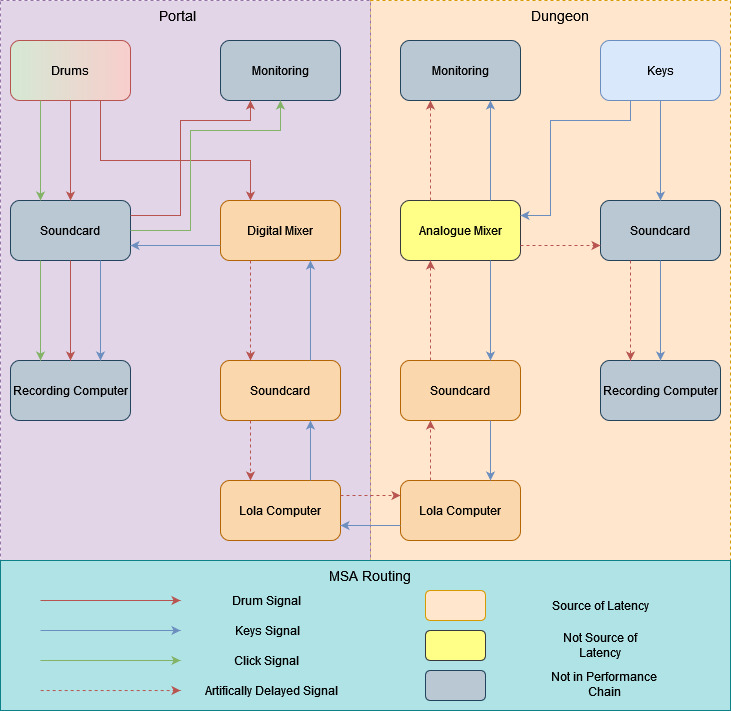

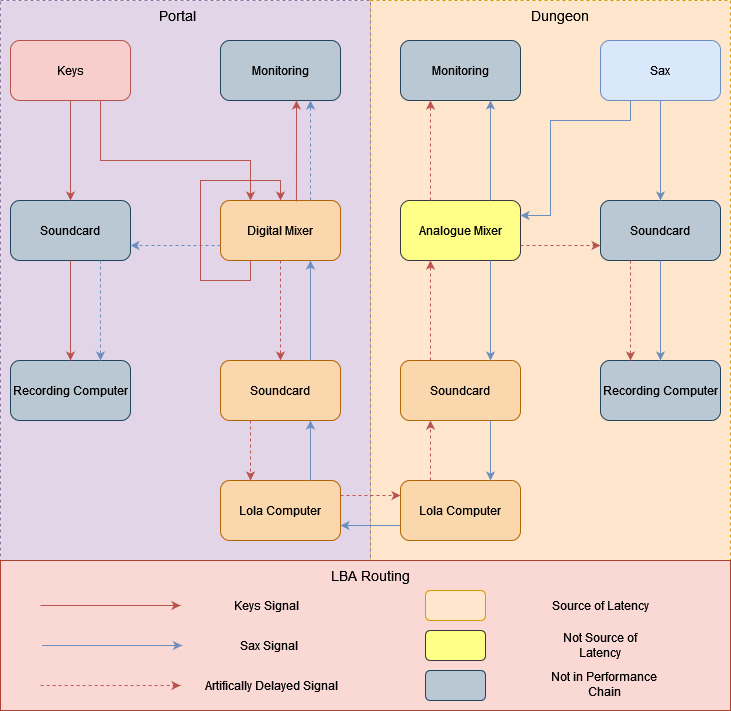

In order to control latency we added delay in the channel-strips of the individual instruments in the Midas M32 mixer in the portal.

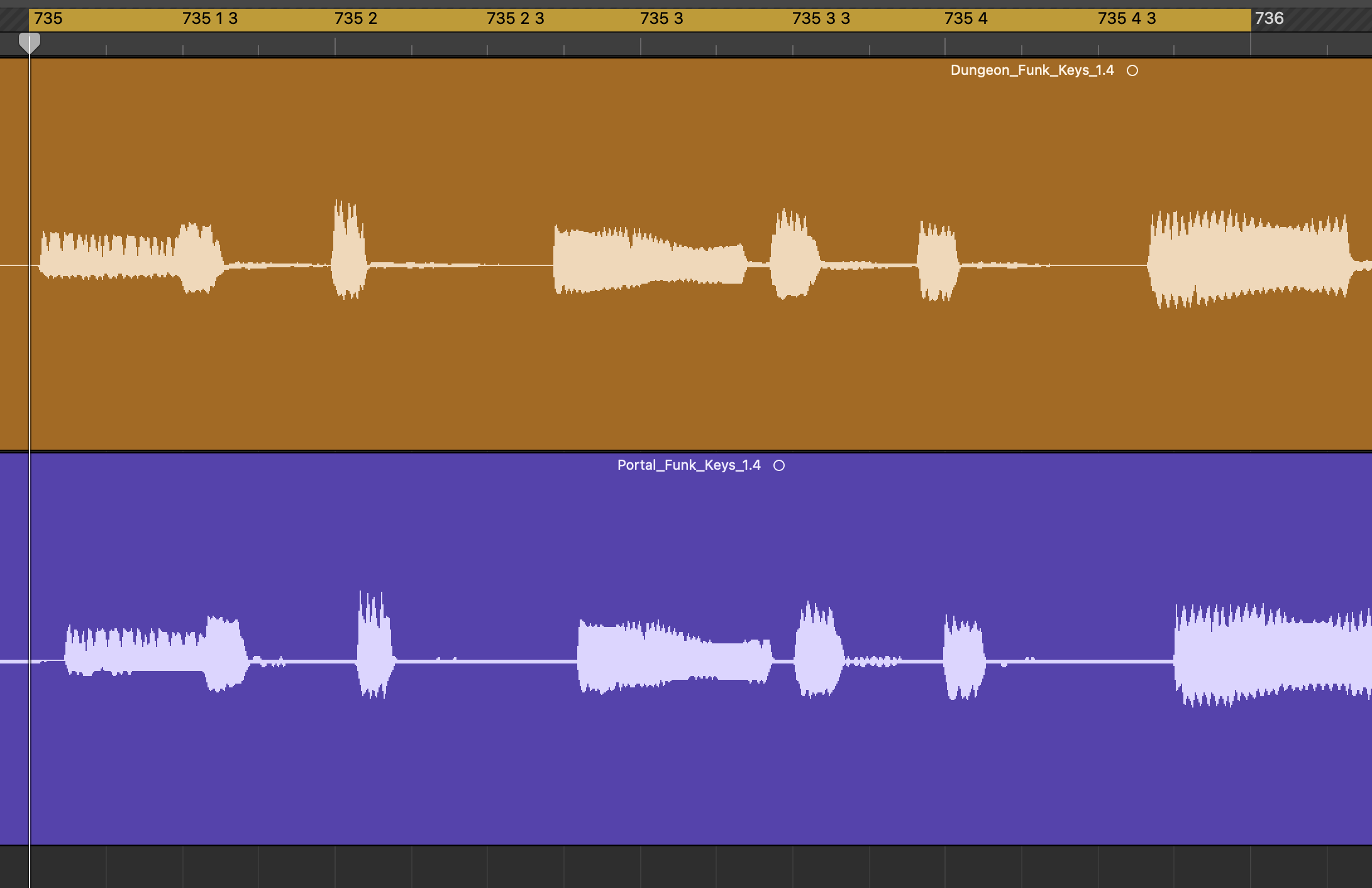

We verified our 20ms measurement by setting a RTT of 300ms (setting the delay on the drums in the Midas to 280ms) and having the drums play a steady beat against a click at 100BPM with the keys playing along on each beat. With one beat at 100BPM having a duration of 600ms, the drummer should hear the keys with exactly two beats delay, which was the case, verifying that our measurement was correct. For the MSA and LBA, we employed similar baseline setups. However, there were some necessary differences to meet the requirements of each of the approaches. For the MSA, a click track was employed for the drummer, which was not to be sent to keys. This was generated within the drum kit, but the signal was split so that it was not also sent to the keys.

Midas M32 Latency Delay

The biggest technical challenge was monitoring. For the MSA this was relatively simple to achieve: the drummer (master) directly monitored the drum kit since they were not to hear the keys (slave) as described in the approach, and the keys could monitor from the mixer. However, for the LBA, the keys (master) required monitoring from the Midas in order to also receive the saxophone (slave), and as latency was applied in the channel strip, directly monitoring this would mean that the keys would be hearing themselves with a delay. Therefore a solution was found by looping the keys into a second channel in which the delay was first added, with the original input channel being sent to the monitoring headphones.

Performance Reflections

- Master-Slave Approach

For Kristian, it didn’t feel too strange to jam along with the drums. However, since Hugh couldn’t hear the keys, there was also no way to communicate musically. This also meant that latency at any delay was not an issue, as what Kristian was doing was irrelevant to Hugh. However, for Hugh this approach didn’t really feel like taking part in a communal musical experience, as he was simply performing a certain number of agreed bars against a click track, and not hearing the music as a whole. This made it feel more like a technical exercise than a musical performance.

Therefore, when playing highly rehearsed music in which responding to another player is not so important over a high latency connection, this approach is viable. However, for simply jamming with a friend there’s another solution that might be preferable.

- Laid-Back Approach

For Kristian, the tempo and style of song had a direct influence on how much latency could be tolerated. For Donna Lee, difficulties in synchronizing timing could be felt at much lower latencies than for Solar, which didn’t feel unnatural until the latency was set to the upper limit of 50ms one-way. A factor playing into this could be that it isn’t as natural to play laid-back on a fast-paced jazz melody, compared to a medium tempo melody with improvisation. As a result, Kristian mostly paid attention to his own tempo on Donna Lee, while Solar offered the ability for more interplay between the performers. Joachim didn’t feel the changes in latency directly, except if Kristian unconsciously adapted to the increasing latency. In view of this, LBA is a better option for jamming with friends over higher latency connections. However, it is not as well suited for faster tempos and highly rehearsed music which requires a steady and synchronised tempo.

Conclusion

Attempting to work with latency, instead of treating it as something to overcome, leads to interesting results in spite of several drawbacks. The two approaches live up to their names, with the MSA definitely creating such a dynamic, and the LBA sounding appropriately laid back. Employing these techniques opens up new possibilities to play together online, even if it isn’t playing together in a way that we are used to.

Relevant papers and links

[1] Carôt, A., & Werner, C. (2009). Fundamentals and principles of musical telepresence. Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts, 1(1), 26-37. https://doi.org/10.7559/citarj.v1i1.6

[2] JackTrip. (2022). Technology. https://jacktrip.org/technology.html