Latency as an opportunity to embrace

In the era of COVID pandemic, online collaborative performance became the only way we can afford the music, but this form of collaboration suffers from audio latency, is there any way we can use it as an advantage?

Is latency always bad?

Latency is everywhere on the earth, and actually, our auditory abilities are built on latency. The sound latency between two ears from the sound source is one of the bases for the human’s sound localization ability, and this is also the basis for the construction of stereo audio, which is particularly adapted to sounds below 1500 Hz and is the fundamental frequency range of the various musical instruments and also the human voice. According to research, People can perceive the directional difference of about 1 to 3 degrees, because of the latency for the sound to reach both ears is about 10 microseconds. Latency also forms our perception of sound space, the latency and proportion between direct and reflected sound allows us to perceive the size and texture of space.

Modern telematic audio systems have always strived for low latency, but in fact, latency has also always been present in traditional music performance. According to sensory-motor synchrony study, There is usually a 30-50ms delay between the musician’s prediction, and sound producing action. Delays are everywhere in music hall. Conductors often give instructions for beats in advance, and even in the best orchestra, musicians are not perfectly synchronised with each other. Actually, imperfection makes the music more human, and these humanities are so rooted in our auditory culture that we can become uncomfortable with perfectly synchronised orchestral music produced by MIDI.

When does the delay become a problem?

Researchers found that in a test involving two Mozart duets, that a latency of anything over 100ms was enough to render the experience either unmusical or non-interactive (Bartlette et al. 2006: 49). Others have observed when the latency around 11ms(Chafe et al. 2004: 1), each performer waits slightly for the other, creating a gradual deceleration in tempo. More extensive studies tend to agree that latencies of between 20 to 30ms are where notable disruptions to performers start to occur(Haas [1949] 1972: 145).

Between NTNU and UiO, we measured around 29ms latency for direct signals, and around 40ms included microphone and speakers. As a result, we can still feel audible latency in the Portal. So, instead of trying to figure out how to reduce latency, we should embrace it and make it part of the music. The first solution is to develop an audio system with fixed latency, and the second solution is to use a special approach to compose telematic music.

Online Orchestra

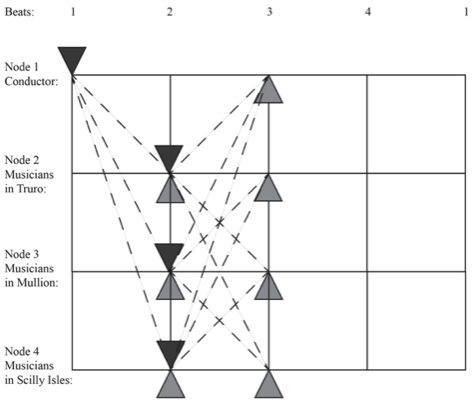

Researchers from the UK have used an idea to develop a system called Online Orchestra. In this system, the software will first check the latency of each part of the system and choose a value bigger than the latency of each part as the tempo of the music and lock the latency, e.g. setting a 500ms latency is equivalent to one beat at a 120BPM music piece, then the latency between each part is one beat. In the figure 1, When the conductor makes a command in the first beat, all the nodes, on the second beat, will receive this signal and make the sound, and these signals, delayed by another beat, return to the conductor side in the third beat and are sounded in unison. Although the sound of each node is inconsistent, at the end, the sound is perfectly harmonised in conductor’s perspective.

Composing for latency

Texture Distribution

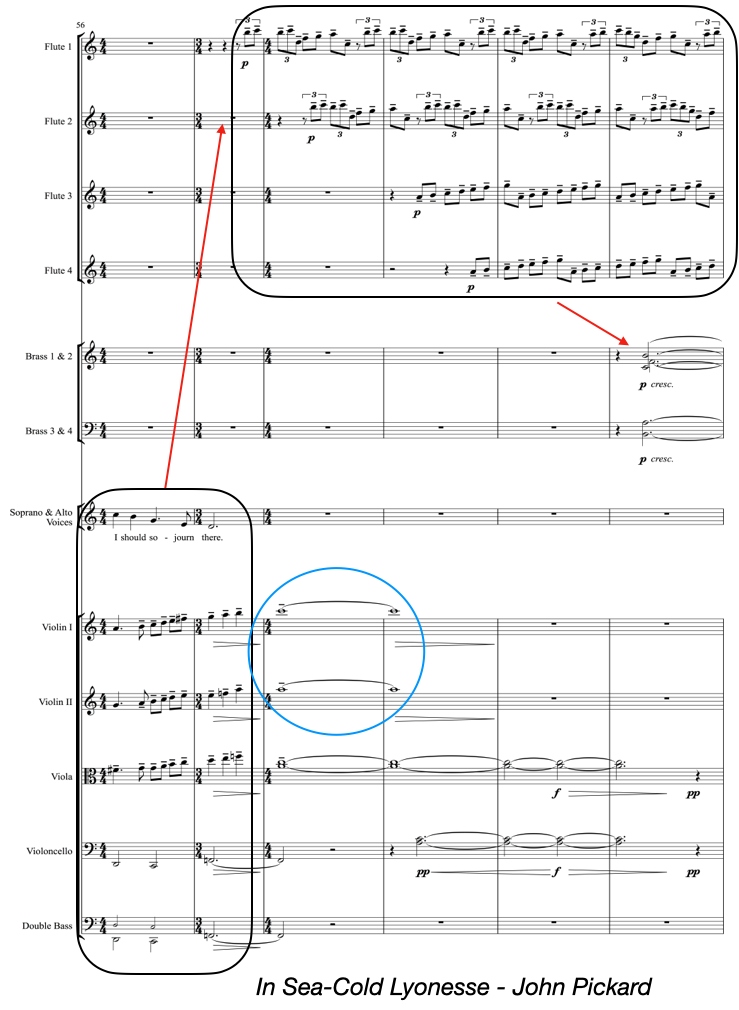

As well as from a technical perspective, we can also compose music for latency using special arrangements. A simple solution is to distribute a texture across the ensemble. This score shows an example of this type of distributed texture. In the music score below, we can see the focus moves from the strings and vocal materials of Node 1 to flutes in Node 2, with the strings imitated in the flutes to smooth the transition. flutes have highly active materials, but this rhythmic activity does not spread to other parts of the ensemble. Latency therefore does not disrupt the overall coherence.

Polyrhythm and Ostinato

The second method here is to arrange polyrhythm and ostinato for complex rhythm, A rhythmic ostinato is a short, constantly repeated rhythmic pattern, the pattern onset points with respect to each other are less significance, especially under the situation that the latency is locked to one beat. We can know more about Ostinato from the video below:

Harmony

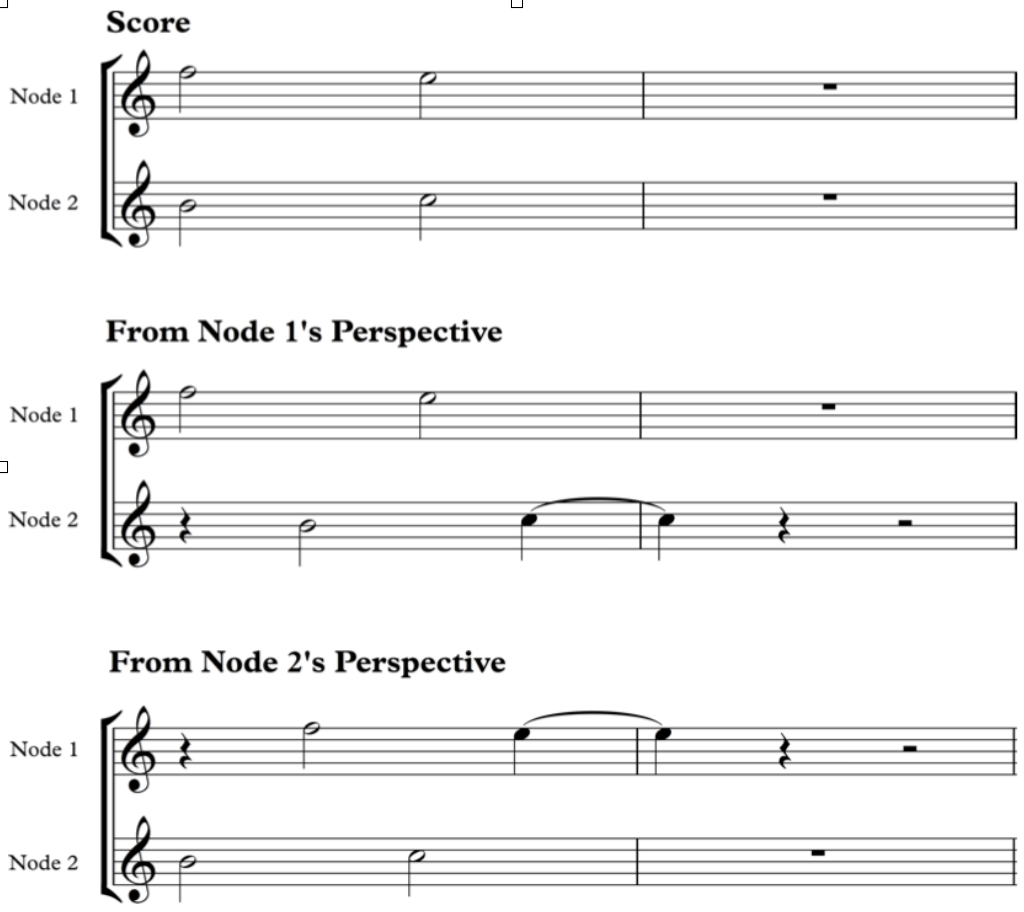

The third option is to prioritize linear music organization, as opposed to vertical harmonic progression. In other words, the harmony determines the colour of the music, and if we blurs and reduces the harmonic transitions in telematic music, the impact of the delay is reduced. Like the score below, the harmony of the music is not affected even though the music is shifted due to the delay.

Conclusion

In summary, we may never get a telematic system with zero latency, but we can embrace latency through rigorous, delicate system design and musical arrangements. Finally, let’s listen an excerpt from In Sea Cold Lyonesse, a telematic performance applied the technical and compositional techniques we have just described. this work spread three locations in the UK and involving over 100 musicians. Hope you enjoy it:)

References

Braasch, Jonas. (2009). The Telematic Music System: Affordances for a New Instrument to Shape the Music of Tomorrow. Contemporary Music Review, 28:4-5, 421-432, DOI: 10.1080/07494460903422404.

Rofe, Michael and Reuben, Federico (2017). Telematic performance and the challenge of latency. The Journal of Music, Technology and Education. 167–183. ISSN 1752-7074 . https://doi.org/10.1386/jmte.10.2-3.167_1

Rofe, M., & Geelhoed, E. (2017). Composing for a latency-rich environment. Journal of Music, Technology & Education, 10(2-3), 231-255.

Mills R. (2019) Telematics, Art and the Evolution of Networked Music Performance. Springer Series on Cultural Computing. Springer, Cham. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uio.no/10.1007/978-3-319-71039-6_2

Palmer, C., & Demos, A. (2021). Are we in time? How predictive coding and dynamical systems explain musical synchrony.