Room acoustics: what are room modes and how do they influence the physical space?

Room acoustics

What are room modes and how do they influence the physical space?

Introducing key concepts

One of the most discussed topics in room acoustics is that of room modes. But what exactly are they and why are they important? Let’s clear out the confusion and misunderstandings together.

Room modes represent the resonant frequencies that occur within a room.

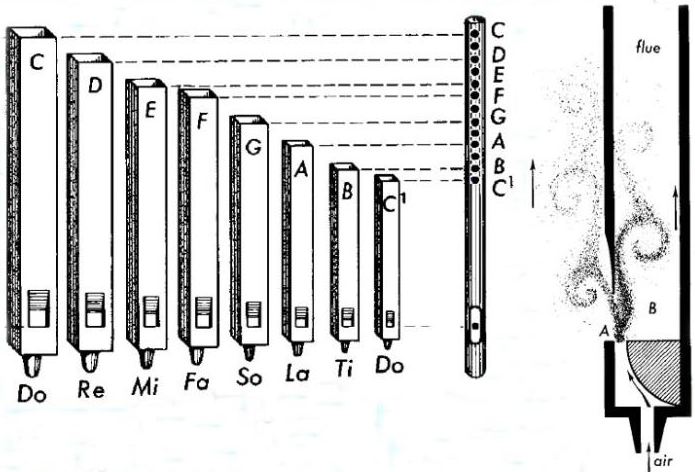

Just like organ pipes, rooms resonate; similarly, just like the different pipe dimensions produce different resonant frequencies, room dimensions also correspond to certain frequencies.

Based on this, the goal when designing a good room for music, conferences, or home theatre systems is to control the decay time and minimize this coloration – strongest at bass frequencies between 20-200 Hz.

When talking about soundwaves, we often think of their frequency first. However, they are also characterized by their wavelength (size) – the distance between two consecutive peaks in a wave. To exemplify, a 1kHz soundwave would have a wavelength of about 0.35m. Lower frequencies have much longer wavelengths – a wave of 150 Hz has a wavelength of 2.28m (almost the height of a normal room!)

Resonance chambers

If you work with sound or play an instrument, then you’re probably already familiar with the way the physical volume affects sound. To produce different frequencies, instruments use strings and chambers of varying sizes – e.g. the difference between a bass and a treble instrument.

Similarly, any room will act as a resonance chamber at specific frequencies depending on its size. For example, if you consider a room with the longest length of 6m, this would correspond to about 56 Hz. The first room mode corresponds with the longest dimension of the room. In the case of our example, 56 Hz would be the first and strongest room mode.

This sounds quite abstract. How can you test it? Simply choose a tone based on your room dimensions and play it over your speakers (it’s important that it has a subwoofer). Now move around the room and observe how in some spots of the room the tone is very strong, whereas in others it suddenly disappears. Crazy, right?!

This is an example of an axial room mode, the strongest type of room modes and the main focus in a rectangular room. The frequencies and wavelengths of such a room correspond with the three axes of the Cartesian coordinates of the room.

When listening to audio in a room with strong room modes, unwanted characteristics are observed at particular frequencies, such as:

- long decay time,

- boominess, and

- apparent pitch changes.

This happens because as a tone with one frequency excites and is then dominated by a strong resonance at a slightly different frequency, the low frequencies then affect the middle and high frequencies.

Nearly all systems, even those with extremely high-end equipment, suffer from the negative impact of modal resonances - e.g. a room with long decay times in the bass range can sound “muddy” or “boomy.”

Practical demonstration

Listen to these recordings of two songs in the same room, each recorded before and after acoustic treatment. Notice how the long decay times affect the clarity of the low-, middle- and upper- frequencies.

Addressing problems of resonance

In a room, the first room mode is not the only one to produce resonance. Each harmonic integer multiples of the fundamental modal resonance will do it too – e.g. a room has the first mode at 80 Hz; it will also resonate at 160/240/320/… Hz. These harmonic resonances are mostly observed as feedback issues in a microphone-speaker setting.

In broadcast and education, speech intelligibility is extremely important (lectures, interview, etc). Thus, controlling decay times is very important for clarity of dialogue, clearing up the low end to give your sub more impact, and alleviating localization problems common with sound systems. Low frequency resonances result in the smearing of vocal frequencies and need to be controlled for clear and concise speech.

Optimizing the MCT portal and other rooms built for teleconferencing and telematic performances

1. “Optimum” Room Dimensions

If a room has evenly divisible dimensions – e.g. a height of 3 m and a length of 6 m – then it’s going to have similar modes: similar frequencies will stack upon themselves and exasperate the problem even more.

So, room dimensions are one way we can control room modes. The standard modal approach for designing a room with good acoustics is to create as many different resonances as possible and to spread them as evenly as possible across the frequency spectrum (see the ‘Handbook for Sound Engineers’). Bigger rooms also reduce the spacing between resonances.

In general, the lower the better for the first resonant frequency, because this region is where the frequency response is most variable.

2. Acoustic Materials

Bass traps and large broadband absorbers are absorbers of acoustic energy designed to damp low-frequency sound-energy. They are typically made from porous materials such as rockwool, mineral wool, basotect, or other types of acoustic foams, and incorporate elements such as membranes, airspaces and additional thicknesses of fiberglass (≥ 6″) – all needed to control low frequency bands.

What is the best place to put them in a room? They are most effective if placed on:

- A tri-corner (e.g. where 2 walls meet the ceiling or the floor);

- A wall/wall corner (e.g. between the side and back wall);

- The ceiling.

A diffuser is any reflective structure that has an irregular surface capable of scattering the reflections. To be effective, it needs to have bumps and humps of at least several inches (≥ 1/4 of wavelengths).

Other effective acoustic materials are soft furnishings that ‘accidentally’ create absorption such as curtains and carpets.

Attention! Porous absorbers (most commonly sound absorbing panels) don’t work on low frequencies unless they are very thick, or placed far enough away from the wall.

For example, for a 200 Hz sound wave, the wavelength is 1125/200 = 5.6 feet; in a sound wave, the velocity is maximum (and the pressure is zero) at ¼ the wavelength from a boundary or the wall; such, a quarter of the example soundwave is 1.4 feet (0.43 meters). You read it right! You need a lot of space to absorb low frequencies using porous absorption!

3. Optimal listener speaker locations

Modal theory tells us that a subwoofer in a room corner will excite all modes. In contrast, for a subwoofer perfectly centered along one wall, several modes will not be excited at all.

So, ideally, the loudspeaker should be out and away from the corners. The optimal placement can be calculated using some good-ol’ math, and then tested by ear and with instruments.

As any other resonance chamber, for a room to resonate, it needs containment. Thus, opening large windows and doors will help relieve the room modes, creating an “escape route”.

4. Digital pre/post Equalization

An effective way of achieving better frequency response is to apply parametric EQ directly on the sound before it is sent out or on the microphone. When two rooms are virtually (and electronically) connected, such as the MCT Portals, this works like a charm – e.g. applying two filters on 35 and 63 Hz. Check out Stephen’s video for more information of feedback equalization.

I hope this blog post helped you gain a better understanding of room modes and the ways to use or misuse them!

Video Tutorial

Here are some other resources and tools for calculation, check out these links: