Telematic Conducting: Modelling real-world orchestral tendencies via video latency

During our collective time in the portal(s), the musical pursuits of the MCT 2020 class have all shared a fairly specific layout. Groups of musicians assemble on each side of the latency chasm and then attempt to find some form of musical understanding while navigating telematic performance. Sometimes these efforts work out; sometimes they don’t. For this assignment, I decided to consider a different approach to telematic music-making, an approach that I actually think might hold substantial promise for satisfying group performance.

I propose that a telematic set-up in which one portal is inhabited by a lone conductor while the other portal contains a complete orchestra would actually provide a situation for music-making with more in common with non-telematic orchestral performance than one might expect.

Note: I encourage anyone reading this to watch the far more detailed 10-minute lecture I have included at the bottom of this page. If you like thoughts on telematic performance and gifs of strange conducting techniques, it will definitely be worth your while.

Conductors… What in the world are they doing?

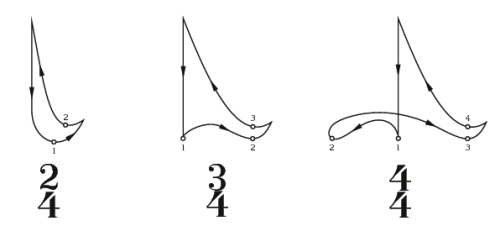

The basic principles of conducting are simple. A conductor provides the tempo and other important musical information to an ensemble via arm, hand, and sometimes bodily movements. Specific patterns correspond to different time signatures, and within these patterns are specific spots that indicate each beat within a measure. The conductor’s motions allow far larger ensembles to play together than could ever coordinate their musical contributions without some kind of leader or musical traffic cop.

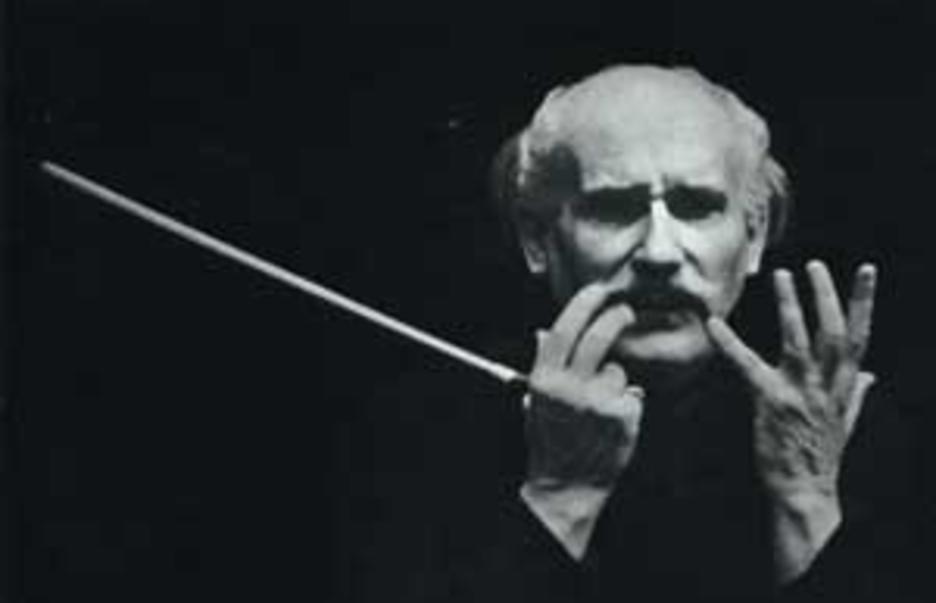

While this is what theoretically happens, reality in high-level ensembles can look a whole lot different.

Professional conductors typically have highly personal styles that might minimise or ignore the traditional ‘beating of time’ completely, instead emphasising stranger motions that only ensembles familiar with their idiosyncrasies can interpret. Most important for our purposes here, many conductors intentionally conduct ahead of their ensembles. This anticipatory conducting means that many ensembles are consistently playing many milliseconds behind their conductors. In short, they’re intentionally producing real-world latency!

“It’s very mysterious … I’ve seen European orchestras respond so far after the beat, that I have no idea how they know exactly where to place that.” JoAnn Falletta, Music Director of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra https://www.wqxr.org/story/why-do-orchestras-play-behind-beat/

(Ignoring for a moment the question of anticipatory conducting, the acoustic profile of an orchestra in a large hall can be extremely complicated. Many ensembles and stages are large enough that sounds initiated simultaneously by players on different parts of the stage might reach the conductor dozens of milliseconds apart. And this isn’t even taking into account the reverberations, instrumental directionality, and individual player attempts to compensate by playing slightly ahead of or behind the greater ensemble. In short, the illusion of a large ensemble playing with perfect synchronicity is only achieved by a combination of savvy players and the reverberant blur of a large hall that smooths musical edges.)

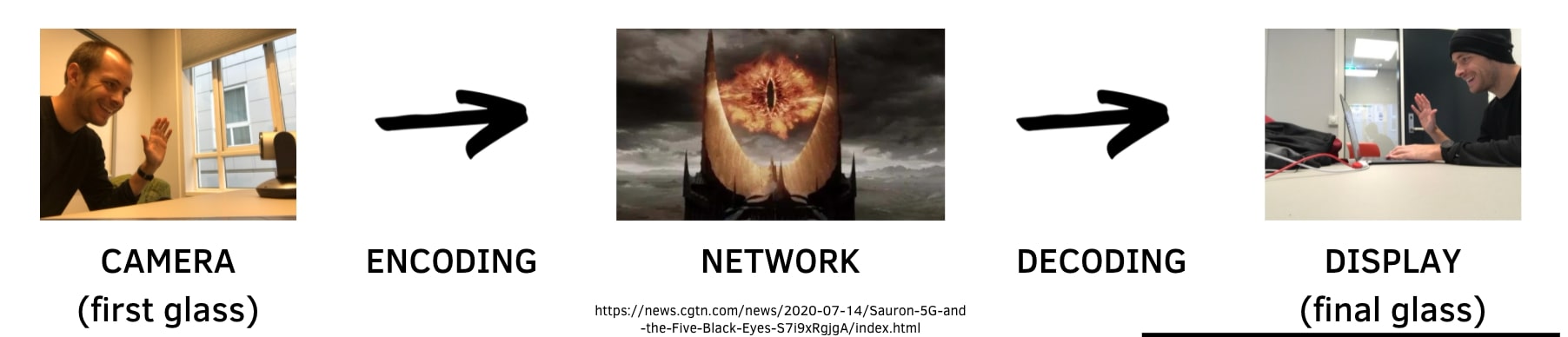

Video latency

Video latency can be defined (in a simplistic sense) as the ‘glass-to-glass’ delay between the initial capture of video and its arrival at the intended destination (the first glass being the initial camera lens and the final glass being the screen on which the video is being displayed). In its journey from start to finish, the video must traverse the chain of camera → encoder → network → decoder → final destination.

While we have a large amount of control over the beginning and end stages of the video’s route, the ‘network’ period is something that is harder to control. This is the stage in which packet loss and degradation of the video information can occur (particularly if we are trying to minimize latency).

This latency (and the equally complicated audio latency that comes with its own challenges) is responsible for much of the challenge of telematic performance. The visual and audio cues on which performers rely to play together are not only delayed, but delayed unequal amounts. For performing between the portals this has often equaled general dissatisfaction for many of us who are more accustomed to live ensemble musicking.

The Conductor ←→ orchestra portal set-up

When one considers the general acoustic chaos that characterises orchestral performance, the concept of placing it within the telematic setting in this specific layout doesn’t seem overly impossible. Conductors and ensembles are accustomed to (and in many aspects have developed by choice) a lattice of differing latencies in their non-telematic practice that somehow don’t seem to negatively impact their musical performances. Moving into a telematic setting would require some negotiation of new latency details, but not details unlike those the participants are already familiar with.

In recent tests, the glass-to-glass video latency between the Trondheim and Oslo portals averaged 45 milliseconds when using Zoom. Assuming at least those speeds, and potentially much better ones should Teico or LoLa be used, our simple Zoom set-up would be adequate for performers who are used to playing with an intentional latency.

The conductor’s perspective

For the conductor, working alone in her or his own portal will primarily mean being accustomed to degrees of both audio and video latency. As I’ve explained above, for many conductors this won’t be at all outside the norm. Conductors might choose to have their orchestras play closer to or further from their beat if the latency feels different to that to which they are accustomed. But the potential for mic-ing orchestral sections or even individual instruments would actually lead to a more unified degree of latency across the ensemble than when playing in an oversized hall.

The players’ perspectives

For players, little would likely change. There would of course likely be a learning curve as they determined the new distance between their played beats and those given by the conductor. But this would be potentially outweighed by the fact that multiple screens could provide a better view of the conductor than available in a non-telematic situation (as long as there is not significant latency between the screens in the local set-up).

Conclusions

Until we are lucky enough to find an orchestra willing to experiment in our portals, this is all theoretical. However, I believe that there is real potential for telematic musicking in the format that I have described here. Orchestras have been successfully combating the challenges of latencies and convoluted reverberations in large concert halls for centuries now. Why wouldn’t they be capable of applying those same approaches to an arguably more controllable, telematic setting?