Applying Actor-Network Methodology to Telematic Network Topologies

In his paper “Interconnected Musical Networks: Toward a Theoretical Framework”, Gil Weinberg proposes several topologies for the classification of telematic musical networks in a fourfold system, based upon a through line of musical-technological historic developments. These topologies are placed along two axes (decentralized to centralized, and synchronous to non-synchronous), and consist of connections between nodes, and in the case of centralized networks, the connection of these nodes to a hub (Weinberg 2005 p. 35). In Weinberg’s topologies, these “input nodes” are specified as “players” (Weinberg 2005 p. 34), and the centralized hub (if present) is noted to be “computerized” (Weinberg 2005 p. 33). In this way, Weinberg draws a clear distinction between the human and the technological; that is that the player input nodes create and manipulate the musical material, with the technological being the tools that facilitate this creation and manipulation. However, we can view these topologies from another perspective, that of actor-network theory, to examine the way in which the technological objects in these networks might also possess an agency of their own. Using the description of actor-network theory found in Robert Strachan’s book “Sonic Technologies: Popular music, Digital culture and the Creative Process” as a starting point, I will go on to refer to Benjamin Piekut’s paper “Actor-Networks in Music History: Clarifications and Critiques” to examine how Weinbergs topologies could be considered too generalised, and that the technologies themselves employed in the network could play a role in its definition.

Strachan describes how, “digital technologies are more than mere tools; they are active and enmeshed within the creative process in a central way[, … that] they are a key part within the socio-technological-human networks that go towards making music in the post-digitization environment” (Strachan 2017 p. 8).1 In this way, “both [humans and objects] have agency [… and that] there is a dispersal of agency across differing biological and non-biological sites” (Strachan 2017 p. 8). He refers to Benjamin Piekut, stating that, “[s]eeing technological/human relationships in this way accounts for the ‘manner in which relationships in the real world multiply, overlap, and change [calling] attention to the motile web of relations that define and enable any actor’s role. The network affords an actor certain ways to work; change the network, and you change the actor’ (Piekut 2014 p. 194)” (Strachan 2017 p. 9, referring to Piekut 2014 p. 194).2

It is worth noting here that in Piekut’s description of actor-network theory, he states that the theory, “decouples agency from intention and will. It is an action or an event – not an intention – that manifests an agency. If something makes a difference, then it is an actor” (Piekut 2014 p. 194).3

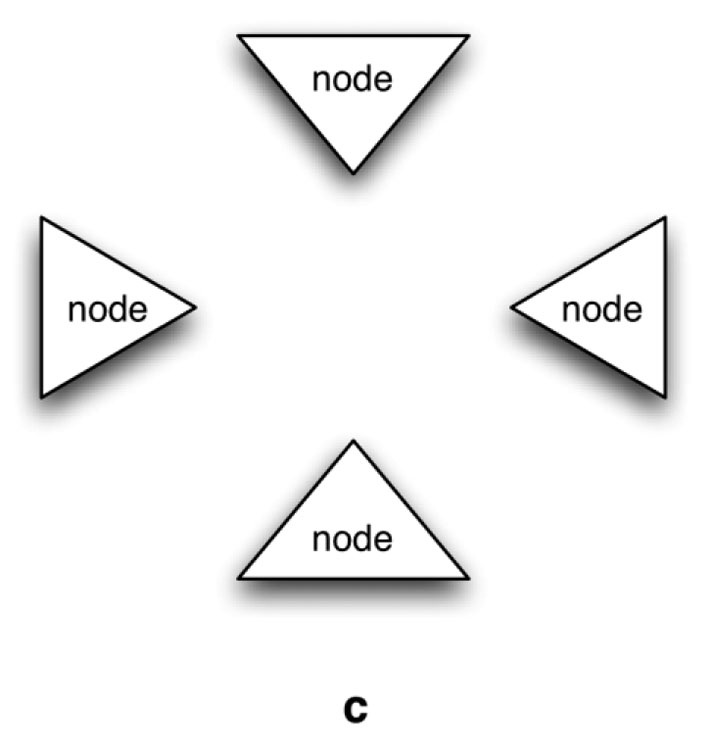

Piekut argues from a music history perspective that actor-network theory should not be considered a theory, but rather, “is a methodology, [and] not a topology; it does not go looking for network-shaped things, but rather attempts to register the effects of anything that acts in a given situation, regardless of whether that actor is human, technological, discursive, or material” (Piekut 2014 p. 193). The aim of employing such a methodology, he argues, is, “[t]o provide an empirically justified description of historical events, one that highlights the controversies, trials, and contingencies of the truth, instead of reporting it as coherent, self-evident, and available for discovery[... and] is above all a methodology that helps us to attenuate normative assumptions about our object of inquiry, to put aside vague or reified concepts such as ‘music’, ‘society’ or even ‘network’” (Piekut 2014 p. 193). It could then be argued that when applying an ANT methodology to the examples named by Weinberg in his paper, the topologies he derives take too broad a view. In attempting to categorize historic performances simply through the creation of a series of technological connecting lines between human input nodes, we are ignoring the agencies of the non-human actors in these networks, which could lead us to overlook cultural and societal elements of such networks when, for example, attempting to recreate them. From this perspective, although John Cage’s Imaginary Landscape No. 4 and the League of Automatic Composer’s Network Computer Music would both tend towards the decentralized-synchronous quadrant of Weinberg’s axes, and would be described with an identical topology when reduced to the player input nodes (See Figure 1), this does not enable an analysis of the distinction in the networks of these performances, namely that of the differing agencies displayed by the most prominent technologies employed in the two works, the transistor radio and the computer. The agencies of these two devices differ greatly, requiring, to name but two examples, different levels of technical knowledge and financial output on behalf of the human actors. As Piekut concisely writes, “[f]or ANT, an actor need not realize, understand, or intend the difference, but it nonetheless should be accounted for in the analysis” (Piekut 2014 p. 196). 1 Strachan’s study is on digital technologies, but his description could equally apply to analogue technologies. 2 It is important to keep clear the distinction between musical networks in a wider sense as referred to by Strachan and Piekut, and telematic networks as referred to by Weinberg. However, Weinberg’s telematic networks do form a subset of wider musical networks, as well as possessing their own relationships to wider cultural and historical contexts. A similar distinction is required when applying the term topology to each of these networks. 3 Piekut also offers a critique of this definition under ANT, stating that, “[i]n fact, despite its provocative stance and the shrill responses it has occasioned, ANT puts forward a weak claim about agency. Something makes a difference. What is it? This minimal notion of agency fosters uncertainty about what an actor might be. From this position of uncertainty, one investigates empirically in order to specify the nature of this agency, somewhere along the ‘many metaphysical shades between full causality and sheer inexistence’.[…] So ANT does not throw out intention or consciousness altogether, but does suggest that differences get made in other ways, too” (Piekut 2014 p. 196, referring to Latour 2007 p. 72). Latour, B. (2007). Reassembling the social: an introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Clarendon lectures in management studies, 1. publ. in pbk. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. Piekut, B. (2014). ‘Actor-Networks in Music History: Clarifications and Critiques’, Twentieth-Century Music, 11: 191–215. DOI: 10.1017/S147857221400005X Strachan, R. (2017). Sonic technologies: popular music, digital culture and the creative process. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic. Weinberg, G. (2005). ‘Interconnected Musical Networks: Toward a Theoretical Framework’, Computer Music Journal, 29/2: 23–39. DOI: 10.1162/0148926054094350

Footnotes

Works Cited