Exploring the influence of expressive body movement on audio parameters of piano performances

1.INTRODUCTION

Musicians move in many ways when performing music, expressive body movements are an integral part of performing music. This attribute, which is shared by all musical cultures (Blacking, 1973), the role of body movement in music performance also has been discussed by researchers for many years. For instance, the musician’s body is described as an intermediary between the physical environment and the individual musical experience (Leman, 2008). From the perception perspective, researchers found that the body movement is important in the expression of musical performance, in addition to acoustic cues, audiences can also perceive musical expressions through body movement, it contributes to the audience understand the score and the performer’s expressive interpretation of music (Davidson 1993,1996; Vines et al., 2003; Dahl and Friberg, 2007; Weiss et al., 2018).

In previous empirical studies, researchers have mainly focused on the cross-modal perception between movement and sound. For example, visual and auditory information is found to be closely linked, influencing the listener’s judgment of the musical performance(Dahl and Friberg, 2007; Castellano et al., 2007). Early research showed that non-musicians mainly use visual cues to perceive expressiveness in violin and piano performances(Davidson, 1993), more recent research demonstrated that although both auditory and visual kinematic cues contribute greatly to the perception of musical expressivity, the effect of visual kinematic cues appears to be stronger(Vuoskoski et al., 2014, 2016). Moreover, Massie-Laberge stated that auditors can distinguish pianists’ different expressive performances in three modalities (audio only, visual-only, or audio-visual) but are better in the audio-visual modality, and the body movement may have a perceptual impact on expressive parameters (Juchniewicz, 2008; Massie-Laberge et al., 2016, 2018).

However, how expressive body movement affects the audio parameters of the music performance remains relatively low progress. Therefore, this project aims to synthesize the method developed by Davidson(1993, 1994) and Wandely(2002) on expressive music performance in different states, to explore the differences in audio parameters and also the body movement features of piano solo performances under three body movement conditions: Deadpan, Normal, and Exaggerated. Normal is defined as the body movements required for normal performance, the performer does not deliberately change his body movements. Deadpan is defined as using only the body movements necessary for the performance and reducing all body movements as much as possible. Exaggerated is defined as an exaggerated expressive body movement, which increases the range of expressive body movement as much as possible when performing. The three different performance conditions all require the pianist to keep the artistic expression as similar as possible.

My main research questions include the following two points: 1) How audio parameters are affected by a modification in expressive body movements? 2) How expressive body movement change when playing under different conditions? I hypothesize that changes in expressive body movement will affect tempo and performance dynamics, and head movement may change drastically under different conditions.

2. METHOD

2.1 Participants and material

Participants

Due to the epidemic and time constraints, the current experiment will only have one piano performer for analysis. The piano performer (male, 23 years old) have more than 15 years professional training and stage performance experience on piano solo performance.

Music material

For the selection of excerpts, three tracks from three composers from the same period, a total of six excerpts were selected, according to the technical difficulty of the music score, all the excerpts were divided into three levels: difficult, medium and easy

• Hungarian Rhapsody No.2, S.244/2-Franz Liszt, Marked as Liszt 1(easy), Liszt 2(difficult), Liszt 3(difficult).

• Ballade No.1, Op.23-Frédéric Chopin, Marked as Chopin1(medium), Chopin2(easy).

• 6 Klavierstücke, Op.118-Johannes Brahms, Marked as Brahms1(medium).

2.2 Procedure

Each excerpt was performed in order in three different conditions three times: Normal, Deadpan, Exaggerated, a total of 54 files were recorded.

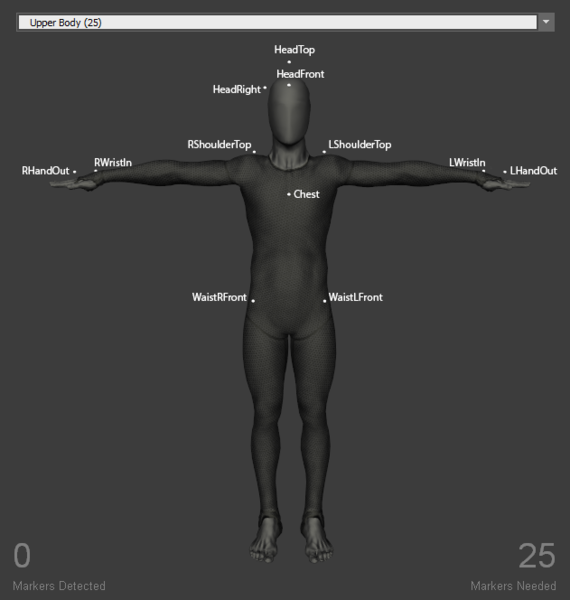

In Motion Capture section, motion data were collected, at a 120 frames per second, with a 8-camera Opti-track Motion Capture in University of Oslo, MCT Portal. Using 25 passive reflective markers on the performer’s heads, wrists, shoulders, torso, elbows and arms, the placement of markers on performer’s body is listed in Figure 1.

In audio recording section, audio and MIDI files were recorded by a pair of AKG C414 microphones in AB Stereo Format and MIDI output through SSL 2+ Audio Interface, sampled at 48 kHz, 24 bit.

Motion capture data will be analyzed through Qualisys and Python, and audio files will be analyzed through Matlab MIR Toolbox and Python Librosa Package.

3. Pianists’ audio and Movement Data Analysis

3.1 Audio analysis

Three audio parameters were analyzed: Duration, RMS and Pulse Clarity. The Duration and RMS were analyzed by Python Librosa package, and the latter parameter was analyzed by MIR Toolbox. Because the last parameter changes too drastically between the performances of the same excerpts, so only Duration and RMS were used in this project.

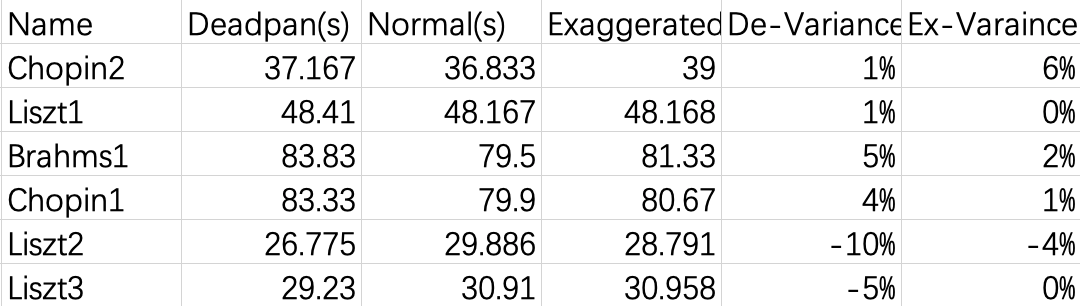

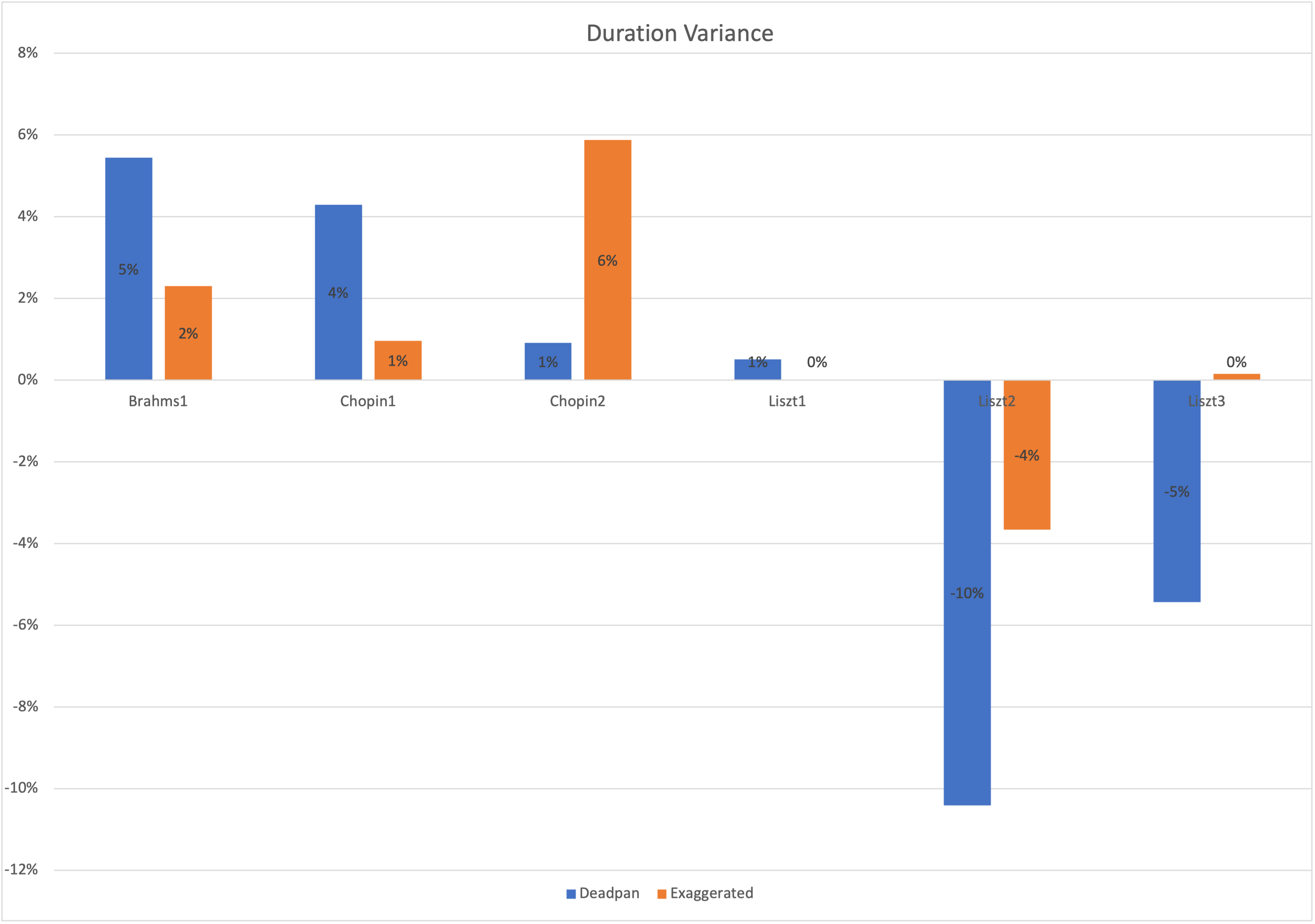

Duration

In this section, I directly compared the duration of the same excerpt in three conditions. After calculating the average duration and variance for the six excerpts in three conditions(sorted from easy to difficult), I found that the difficult excerpts become faster with restricted body movement. In addition, the modified body movements made the easy level excerpts like Brahms1/Chopin1 slower than the normal version. Moreover, the body movement modifications rarely affect the duration in the two excerpts with the lowest difficulty factors, which also the two slowest excerpts.

From the perspective of variance, I found that restricting body movement can affect the performance’s duration more than exaggerating them. and it is also matches the performer’s subjective feeling: It is more difficult to control the performance by restricting body movement than exaggerating body movement.

Dynamic

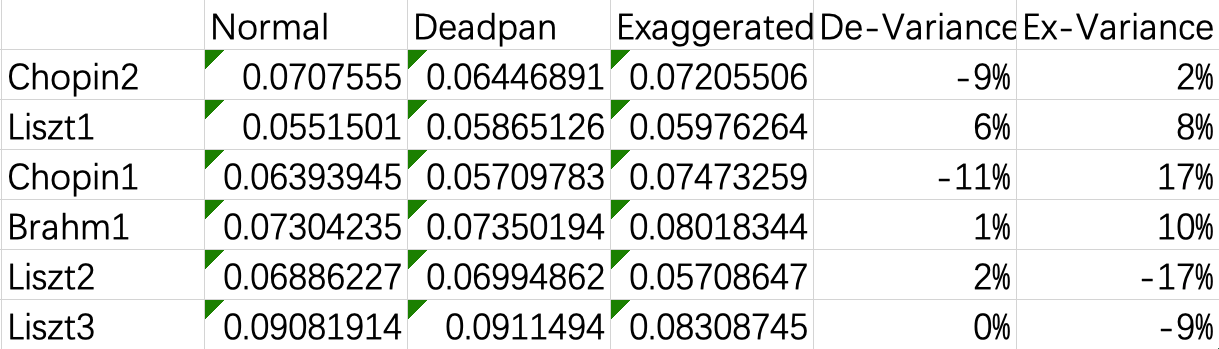

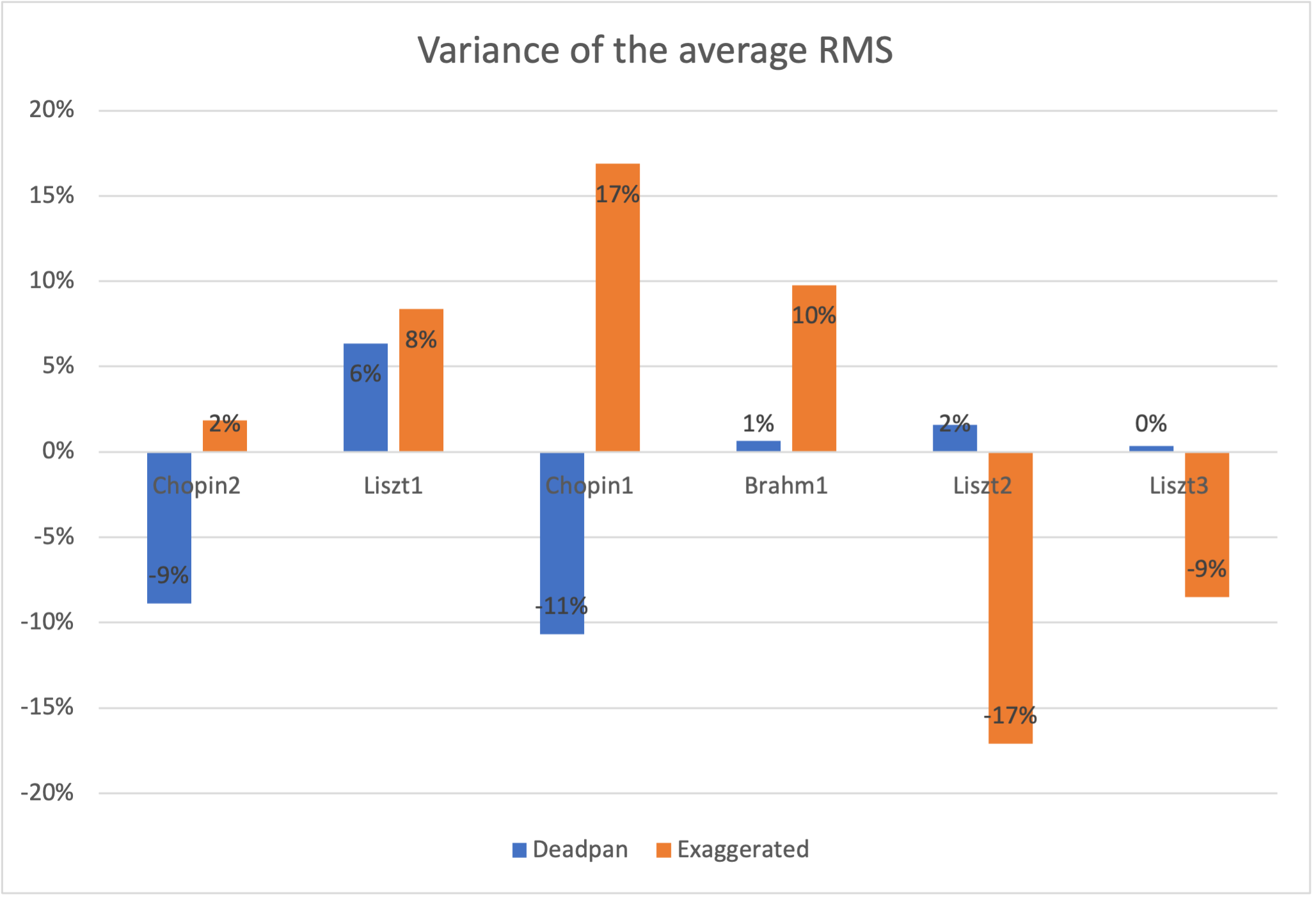

The RMS indicates the average energy of the audio file, as all the files recorded in the same amplifier level, mic position, and piano position, so comparing the average RMS for audio files between the different conditions gives an indication for the dynamic of the performance.

As the data stated in Figure 5, I found that in the two difficult excerpts, the dynamics were significantly reduced under the exaggerated condition. According to the performer’s feedback, this is likely because the difficulty and the higher speed of the notes made hands span a lot, and the exaggerated movements made the fingers touches shallower and the sound intensity becomes less, which is typical of a lack of control in piano pedagogy.

Moreover, from the RMS Variance, it is clear that exaggerated condition could affect more on RMS rather than deadpan condition.

3.2 Body movement analysis

In this section, motion capture data of three excerpts (Brahms1, Liszt3, Chopin2) from different levels of difficulty are selected for presentation. In data analysis, 21 of the 25 measurement points are used. According to the position of the human body, these are grouped into six parts: head, shoulders, elbows, wrists, arms, and torso.

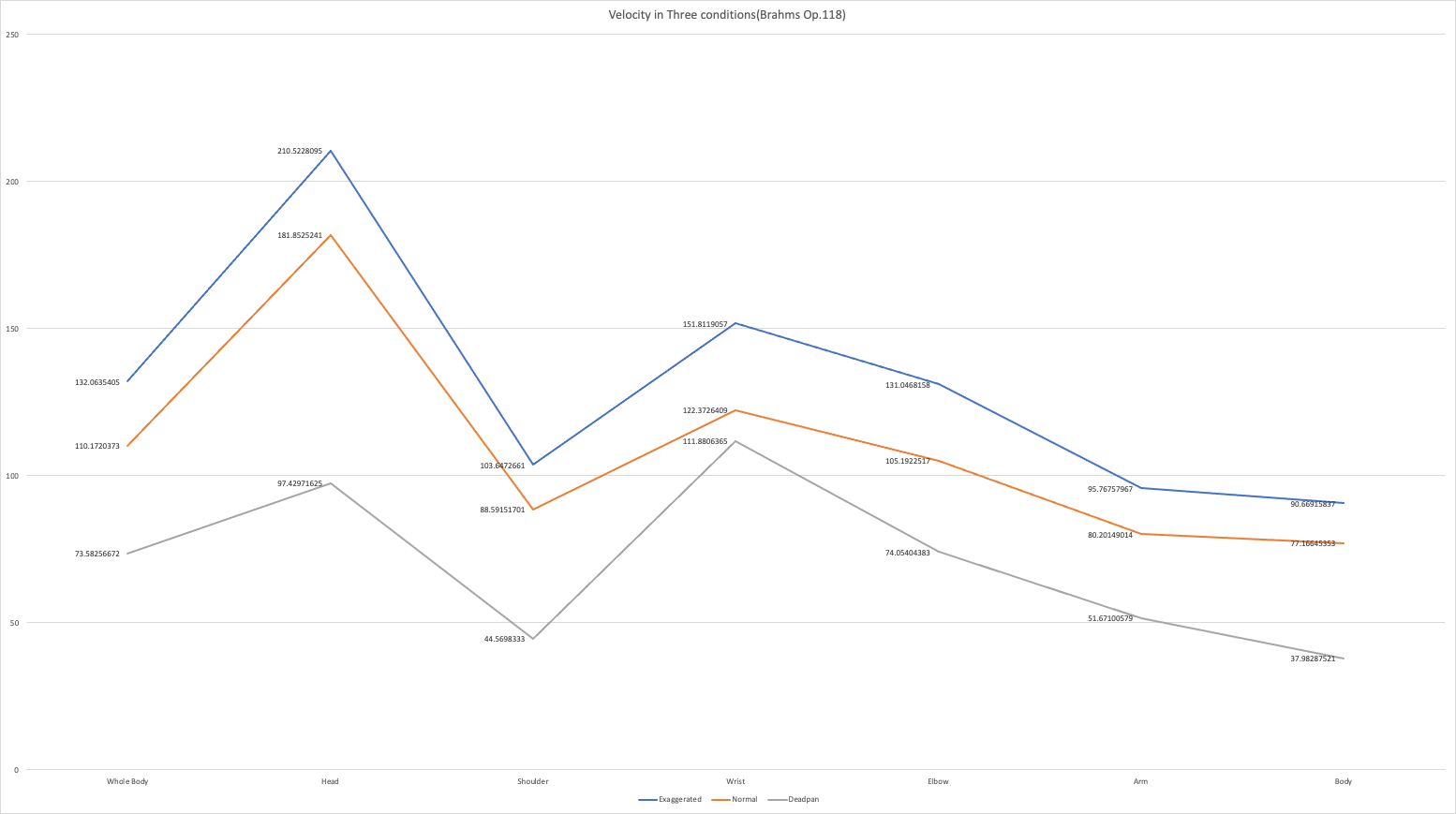

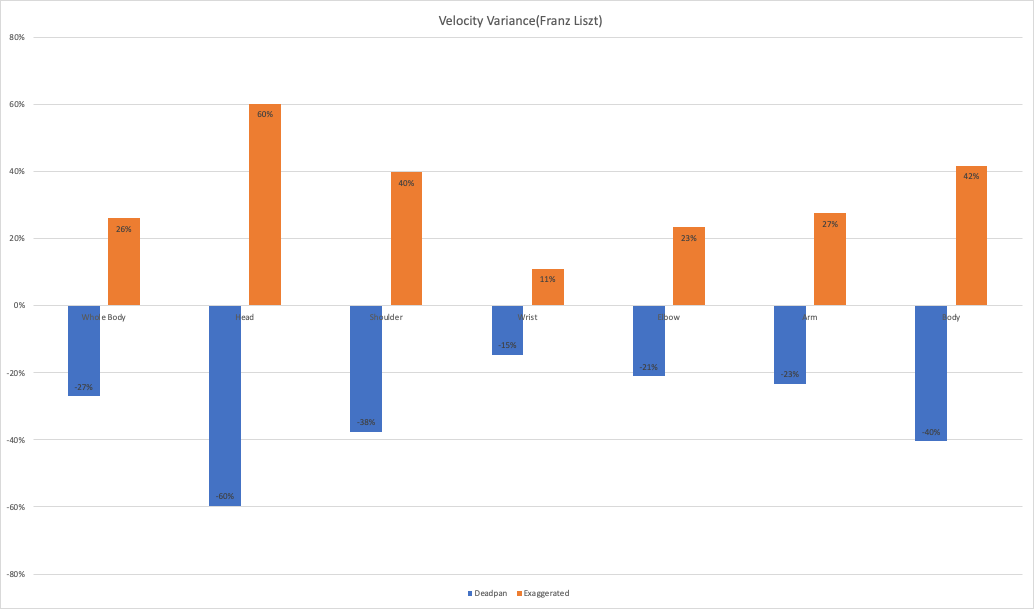

Movement Velocity

By calculating the average movement velocity of each part of the body, I found that under the three movement conditions of all six excerpts, the movement velocity of the head and wrist are the fastest, and the velocity of the shoulder and torso are the slowest. Moreover, the velocity of the wrist is positively correlated with the average tempo of the excerpt.

When comparing the movement velocity variance of three different conditions, I found that the variance of the velocity of the head is the largest, but there is almost no change in the wrist. My assumption is that the movement velocity of the wrist is mainly related to the difficulty, tempo, and structure of the music content, and has less connection with expressive body movement during the performance.

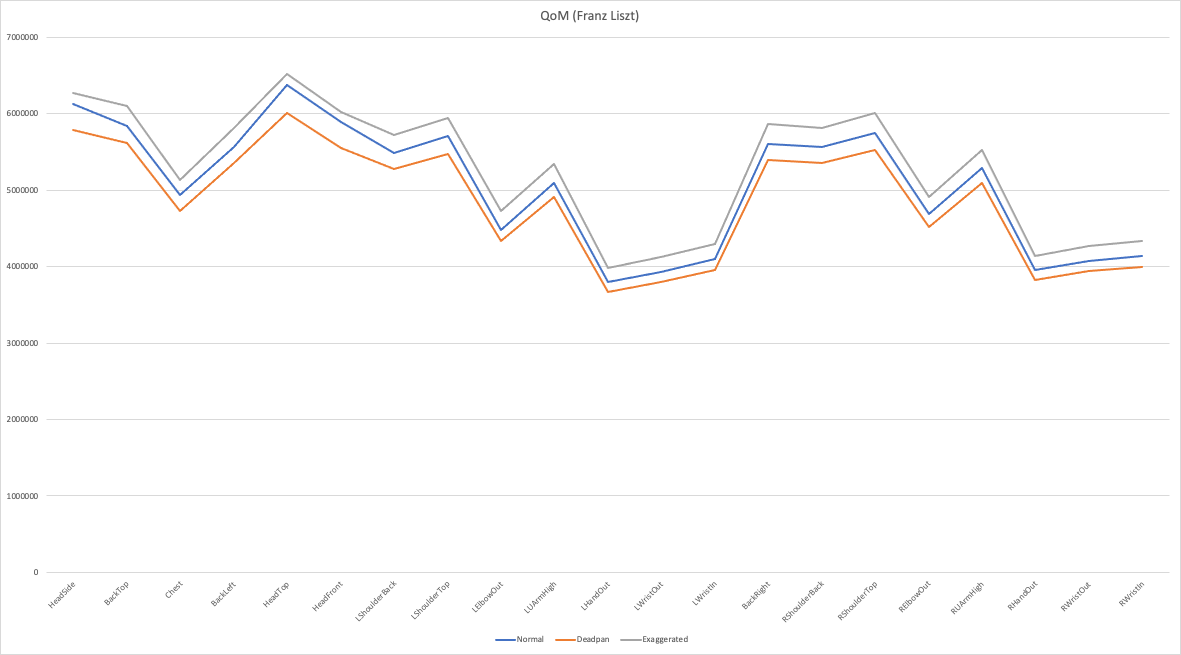

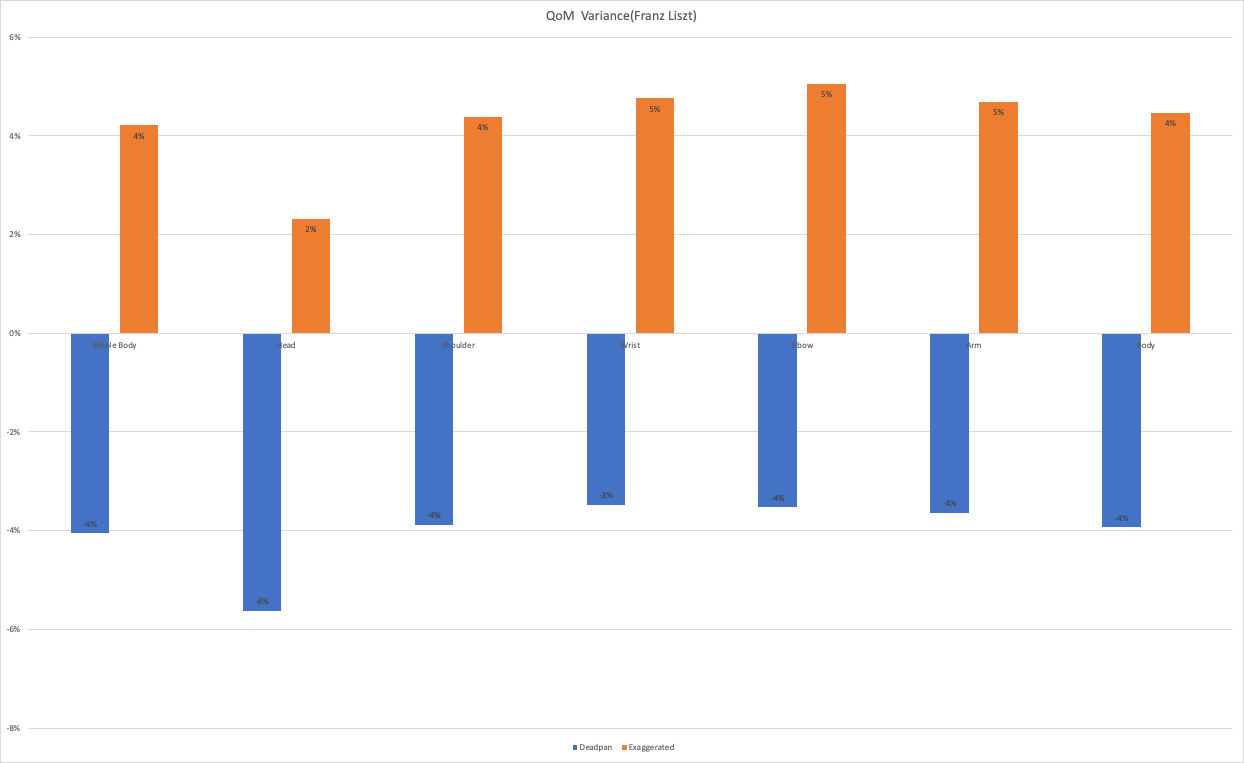

Quantity of Movement

In the QoM analysis, I found that the amount of head and shoulder movement is the highest, while the wrist is the lowest. This pattern also has been found in other excerpts, which is related to classic piano performance skill, that is, stability of the wrist is vital to maintaining the tone of a classic piano piece.

As for the variance of QoM in three conditions. The change in head movement was the most variable across the three conditions, followed closely by the shoulders and elbows. Meanwhile, through qualitative observation, I found that in the Deadpan condition, the amount of head movement is significantly reduced. This may be because, from a kinematics point of view, the direct contribution of head movement to sound-producing activity is not obvious enough.

4. CONCLUSION

Through the analysis of audio, we can draw the following tentative conclusions:

• Changes in expressive body movements affect the tempo and dynamics of the piano performance, which is related to the difficulty of the music, with the higher the difficulty factor the bigger the impact on the music.

• Comparing with exaggerated expressive body movements, restricting expressive body movements will affect music performance more drastically.

• Exaggerated expressive body movements may affect sound dynamic significantly.

From the analysis of body movement, we can also have following initial conclusions:

• The head, wrists move faster during the piano performance, while the arms and shoulders move the slowest.

• The movement velocity of the head, shoulders and torso is greatly affected by playing under different conditions, while the wrist and elbows are hardly affected by restrictions or exaggerated conditions.

• The head and shoulders have the largest QoM, while the wrist QoM is the smallest.

• The QoM of head varies significantly in different conditions.

• The expressive body movement are closely linked to piano pedagogy.

5. Reflection and Future Work

Through this exploration and analysis of expressive body movements in piano performances, it is not difficult to find that body movement have a very obvious impact on the audio parameters of piano performance. This also matches the previous empirical research (Davidson 1993,1996; Vines et al., 2003; Dahl and Friberg, 2007; Massie-Laberge et al., 2016, 2018). However, in this experiment, there was only one participant, both audio and body movement data was not comprehensive enough. Moreover, the use of the electric piano during the recording affected the performer’s performance to some extent. Hence, the conclusions can only be used for reference.

In future work, in addition to study the variation of audio parameters from a more detailed, micro-structured level, exploring the subjective perception of the music produced under different expressive body movement conditions is also a worthwhile research direction. The combination of subjective and objective analysis method will certainly provide a more comprehensive and convincing way out for this research.

6. REFERENCE

Blacking, J. (1973). How musical is man? Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

G. Castellano, S. D. Villalba, and A. Camurri, (2007). “Recognising human emotions from body movement and gesture dynamics,” in International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction, A. C. R. PaivaRui, R. Prada, and R. W. Picard, Eds., Berlin: Springer Verlag, 2007, pp. 71–82.

S. Dahl and A. Friberg, (2007). “Visual perception of expressiveness in musicians’ body movements,” Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 24, no. 5, pp. 433– 454, 2007.

Massie-Laberge, Catherine & Cossette, Isabelle & Wanderley, Marcelo. (2018). Kinematic Analysis of Pianists’ Expressive Performances of Romantic Excerpts: Applications for Enhanced Pedagogical Approaches. Frontiers in Psychology. 9. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02725.

Massie-Laberge, Catherine & Cossette, Isabelle & Wanderley, Marcelo. (2016). Hearing the Gesture: Perception of Body Actions in Romantic Piano Performances.

Goebl, W. (2017). Movement and touch in piano performance, In B. Muller & S. I. Wolf (Eds.). ¨ Handbook of Human Motion (pp. 1–18), Berlin: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-30808-1 109-1.

Juchniewicz, Jay. (2008). The influence of physical movement on the perception of musical performance. Psychology of Music - PSYCHOL MUSIC. 36. 417-427. 10.1177/0305735607086046.

Nusseck M., Wanderley M.M., Spahn C. (2018) Body Movements in Music Performances: The Example of Clarinet Players. In: Müller B., Wolf S. (eds) Handbook of Human Motion. Springer, Cham.

Sarasúa, A., Caramiaux, B., Tanaka, A., & Ortiz, M. (2017, June). Datasets for the analysis of expressive musical gestures. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Movement Computing (pp. 1-4).

Thompson, M. R., & Luck, G. (2012). Exploring relationships between pianists’ body movements, their expressive intentions, and structural elements of the music. Musicae Scientiae, 16(1), 19-40.

Vuoskoski, J. K., Thompson, M. R., Clarke, E. F., & Spence, C. (2014). Crossmodal interactions in the perception of expressivity in musical performance. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 76(2), 591-604.

Vuoskoski, J. K., Thompson, M. R., Spence, C., & Clarke, E. F. (2016). Interaction of sight and sound in the perception and experience of musical performance. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 33(4), 457-471.

Vuoskoski, J. K., Gatti, E., Spence, C., & Clarke, E. F. (2016). Do visual cues intensify the emotional responses evoked by musical performance? A psychophysiological investigation. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain, 26(2), 179.

Jensenius, Alexander Refsum; Wanderley, Marcelo M.; Godøy, Rolf Inge & Leman, Marc (2010). Musical Gestures: concepts and methods in research, In Rolf Inge Godøy & Marc Leman (ed.), Musical Gestures: Sound, Movement, and Meaning. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-99887-1.

Leman, Marc & Godøy, Rolf Inge (2010). Why Study Musical Gestures?, In Rolf Inge Godøy & Marc Leman (ed.), Musical Gestures: Sound, Movement, and Meaning. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-99887-1.