Motion (and emotion) in recording

Back in the nineties I used to play in a band known for it’s energic live-shows and none of this came through on the record we’d just recorded. What happened, where did the energy go? We were a trio, and even overdubbing stuff in the studio, it still sounded thin and boring. How could it be that our audience went nuts, with their pogo-jumping and dancing, on our concerts if that was what we sounded like? Where they just being polite, or maybe very easy-pleasy? Or was it rather that we–in the recording process–lost something on the way? Questions like these has followed me ever since, and even if I’ve started to find my own way of recording myself, I’m still searching for answers on how to capture the intended vibe of the music being performed and recorded. And for this project, I thought I could start to investigate matters like these a little closer.

TAPES AND HARD DRIVES

I will not go into historical details of music and sound recording, internet is full of that for whomever wants to read more about it (check this or that for instance). But in terms of early recording techniques in popular music, one could briefly say that placing a microphone in a room with musicians playing live (full songs, or even full concerts), and press rec on tape, was the main way to do recording. This technique leaves most of the end result up to the musicians performances and the quality of the equipment used, and leaves little to nothing for post-processing. As studio equipment evolves over time, the introduction of multitrack recording and more advanced mixers, post processing becomes more important. During the 60’s the musicians could record each their part alone, one by one, and the studio technician could equalize and pan the individual tracks. And in the very end, when all tracks were recorded, a mixdown to a stereo track would occur. Today, when basically all sound recording eventually ends up on a harddrive, with laptops being able to record an (almost) infinite number of tracks, with endless possibilities when it comes to effects and mixing facilities, musicians can even play only parts of their songs, taking away a lot of the performance, leaving the end result to duplication, sampling and all other post processing one can imagine

MOTION, EMOTION AND MUSIC

So, back to this project of mine. After struggling with how to use motion tracking in a project that also made sense to me, I thought it could be interesting to see if there were some correlation between motion and recorded sound. And I wanted to implement the issues of the different mindset of pre and post processing of the sound. These days people can record the dry signal of a guitar, and leave most everything to post processing. Friends of mine in a metal-band recorded guitar DI with only a generic distortion for monitoring when playing, and then did all processing post recording (in the mix). At the other end of the scale, other friends of mine prefer to do most processing pre recording; meaning using their own effects, their own amp and preferably play it at the correct volume, for the perfect break-up of the amp and so on. The post-processing of the guitar-sound will then be more some sort of adjusting or compensating, as opposed to actually creating the sound. In the first situation, one could argue that for instance the dynamics of the playing could be heavily affected, when not using the gear you are used to. Overdrives and distortions are a quite personal thing for many guitar players, myself included, and they will all sound different with different equipment in the signal chain, and with different playing styles. So one question that comes to mind is: will this method of recording affect the playing of the guitar player, and if so, how? My own preference lean more towards the latter, and I have a belief that the perceived sound while playing, also greatly affect ones playing. And it also may reflect in the players emotions, as well as the motions, while playing.

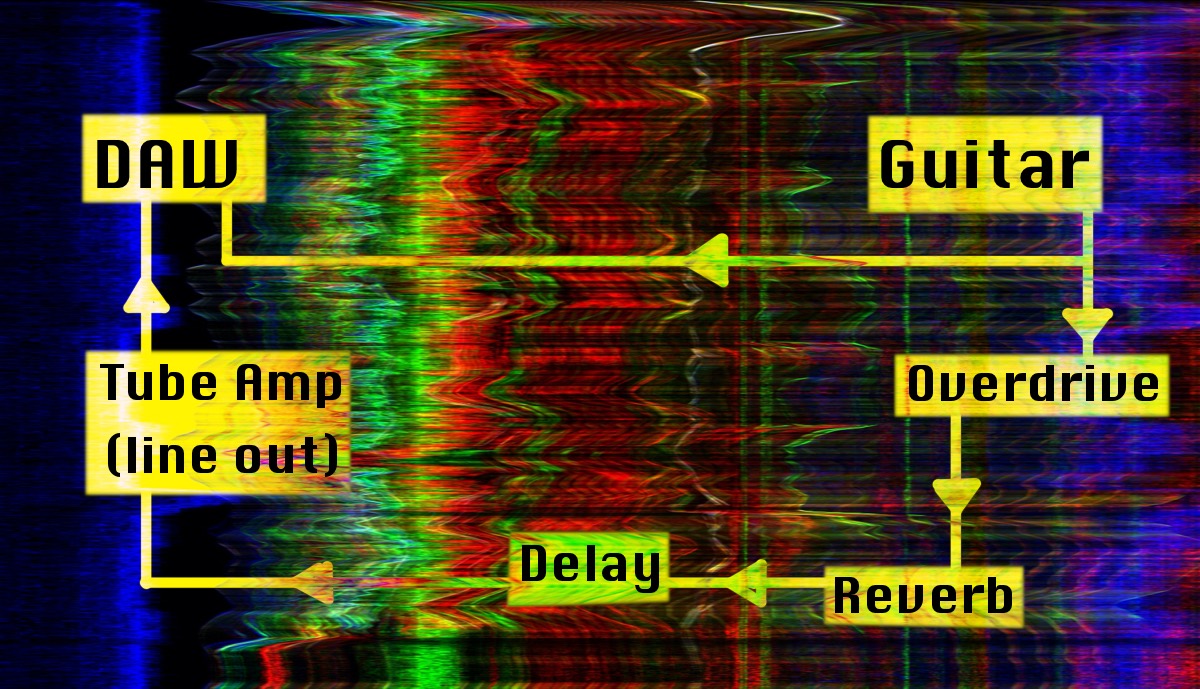

THE SETUP

So I connected my guitar and split the signal path as shown in fig. 1 into one direct input to my DAW (input 1), and the other path going guitar –> overdrive –> reverb –> delay –> tube amp (with line out signal) –> DAW (input 2). With this setup, I was able to record both the wet and the dry signal in one take, and I could choose whether to monitor (using headphones) the wet or the dry signal.

I decided to do the experiment with 16 bars of a slow song I play in a band, with a quite atmospheric sound (lots of reverb and delays) playing chords. Using my iPhone as camera, I first played it when monitoring the wet signal, which is the sound I’m trying to achieve as an end result. And then I played it again, when monitoring the dry sound.

VIDEO ANALYSIS

Before importing the videos to the VideoAnalysis application, I cut both videos to 16 bars, so that the lenght of it was the same (well, they were 1107 and 1103 frames). Below you can see crops of the two videos (no sound).

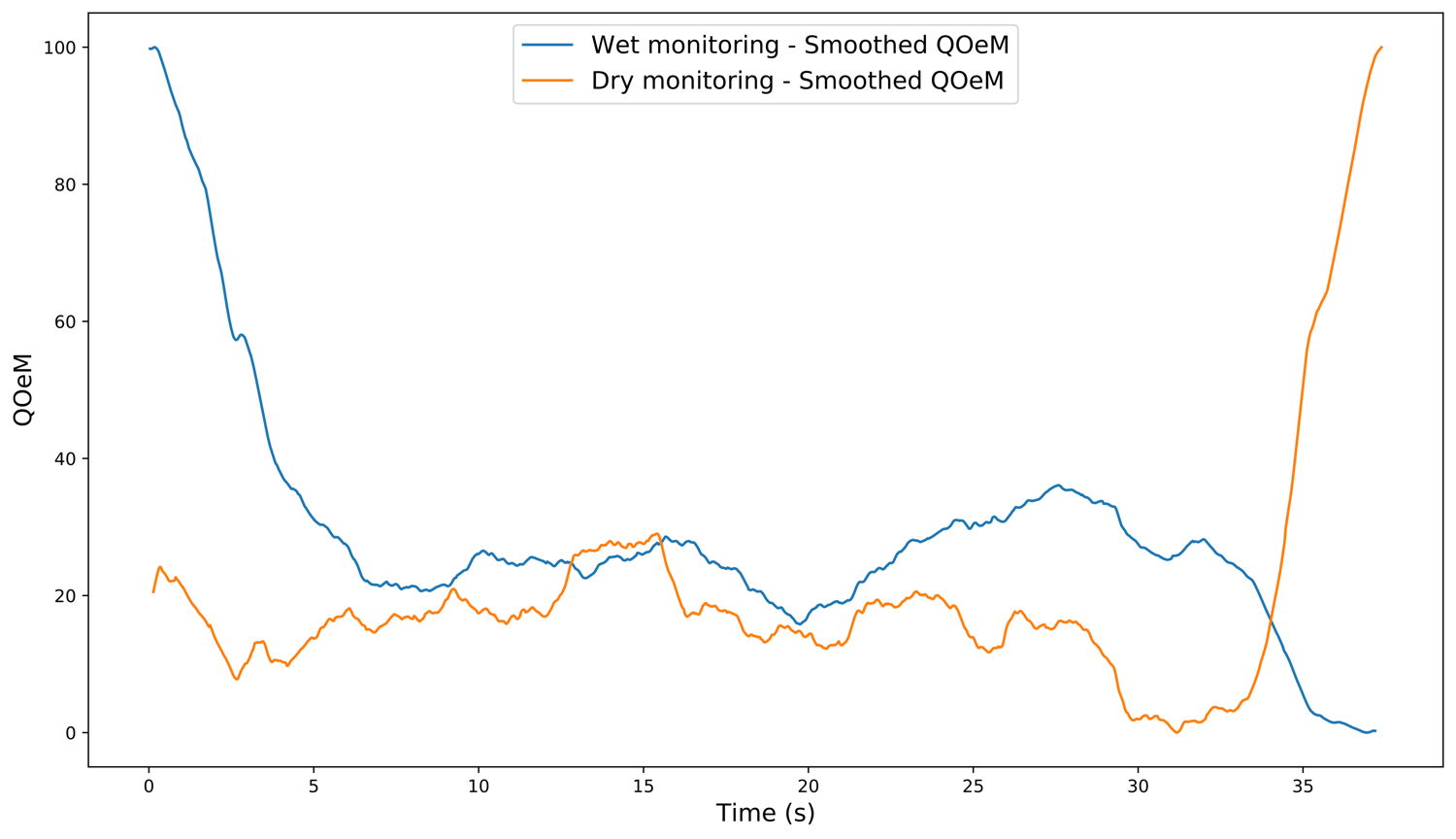

As you can see, the playing and thus the body motion (and emotion as well, quite visible in my face and body language [I’d say—knowing myself]) in the two videos differs quite a lot. When recording them I felt more uncomfortable in the one I only could hear the dry signal, where as monitoring the wet signal, I felt a lot more familiar. I did one take with each monitoring options; I didn’t want to rehears too much for each monitoring, and as a result I adjusted my playing technique after what I felt was better for the perceived sound. Before using VideoAnalysis to analyze, it’s interesting to se how the I in the left image of the video is standing quite still at the end, where as in the right image—when monitoring the dry signal—quickly bends towards the computer to stop the recording. In my headphones, the sound quickly died, due to no reverb and delays in the monitoring, and I also cannot wait to be done with the recording, which felt awkward and strange. I analysed the exported .csv-file from VideoAnalysis in python, and as one can see from the graph in fig. 2, the quantity of motion (QOM) peaked at the end of the dry-monitoring video.

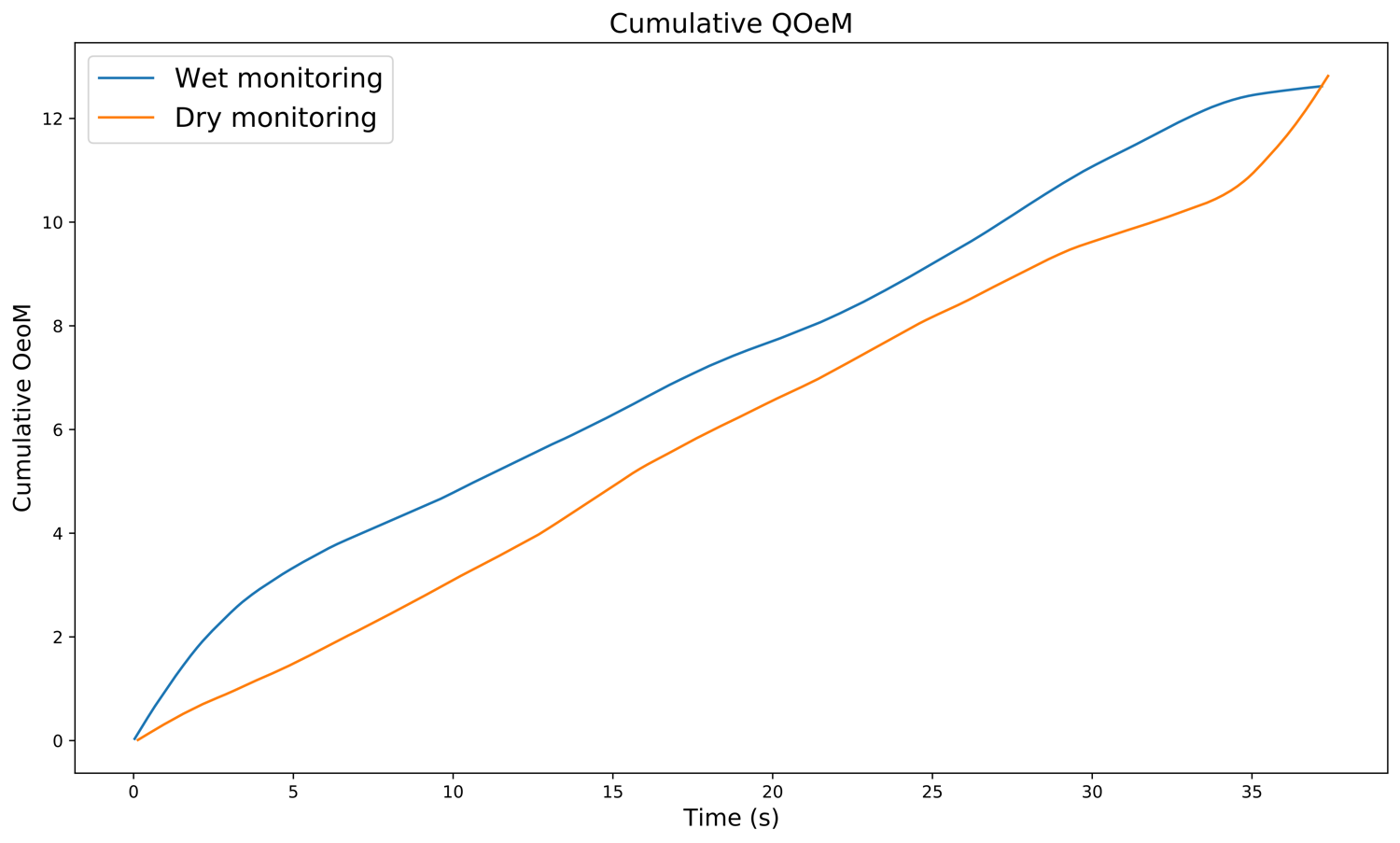

But you also see that in general the QOM seems higher in the wet-monitoring video, as the cumulative QOM-graph (fig. 3) also shows (even though the dry-monitoring actually rises above at the very end). It could be argued that if I pulled out eight bars or so in the middle of the musical phrase, the result would be close to equal, as the graphs in fig. 3 follows each other quite consistently. While this is true, I would argue that the first motions in the wet-monitoring video is very music-related, and thus cannot be left out of the analysis. I could only analyse the first eight bars instead, and then the cumulative difference would be greater than it is now, because of lacking the last not-so-musically related end of the dry-monitoring video. But leaving also that part in is interesting, because it might tell us something about the emotion of the player.

Another thing to point out, which might relate to the emotion of the player, is how the wet-monitoring graph in fig. 2 seems a little smoother than the dry-monitoring one, that could be described as more un-even and less musical, maybe. Could this also be related to the players emotion?

PICTURES OF YOU

In some of the pictures exported from VideoAnalysis one can see similar trends. In fig. 4 I’ve placed the two average images (based on taking the average of all images in video stream), one from each video, and the fact that my head is more transparent on the wet-monitoring image, shows that there’s more motion going on. Maybe also the head-movements are more closely linked to the players emotions?

In fig. 5, the greyscaled motion average images (based on taking the average of all motion images in video stream) it’s also obvious that for instance my right hand is moving more along the string-directions (to the tremolo arm, and possibly also playing more with different points of pick attacks). The neck of the guitar also has a broader grey area, meaning it moves more in the wet-monitoring video.

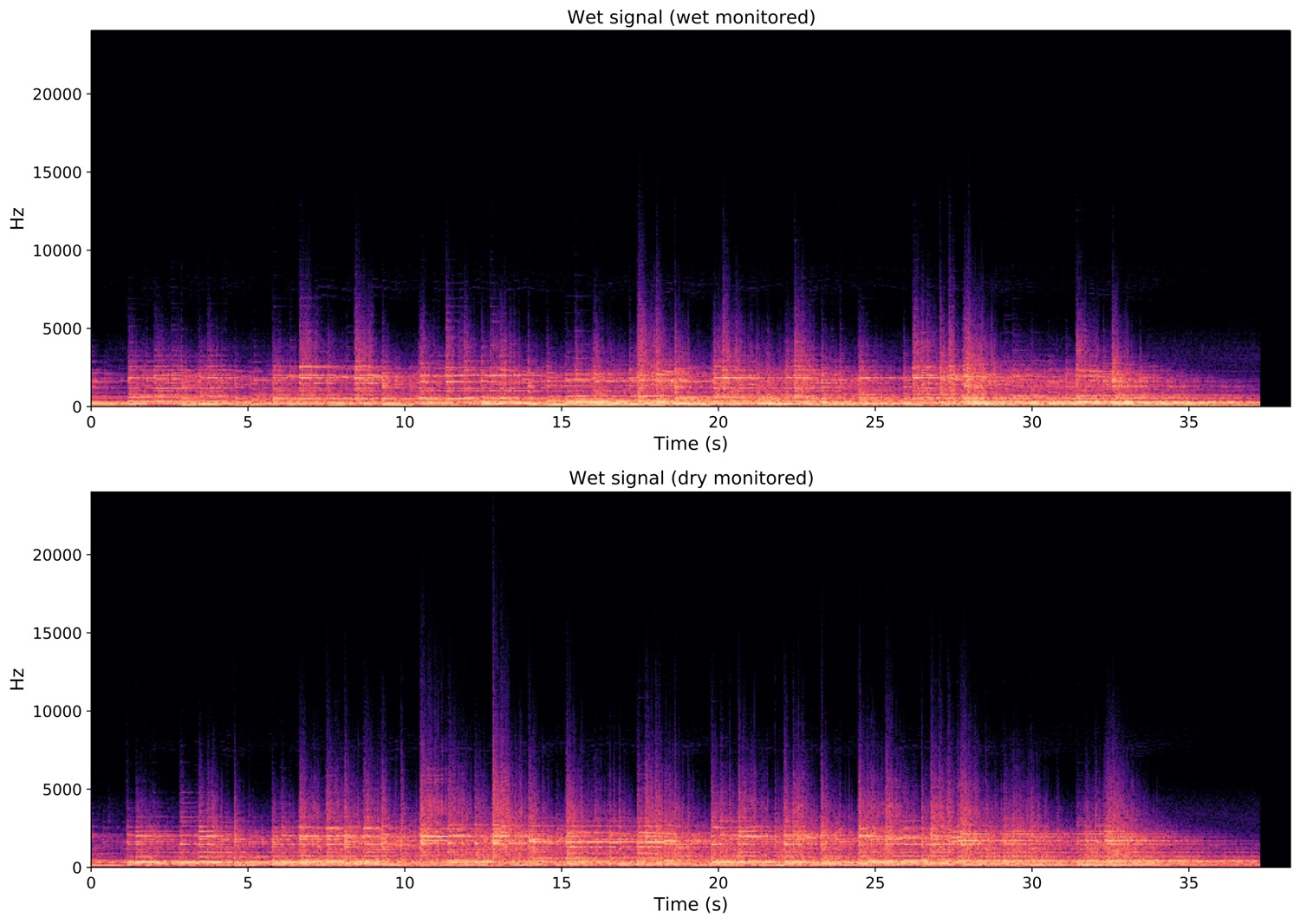

SOUND ANALYSIS

There are apparent differences in the motion in the two videos, but how does the wet signal sound in both the cases. I aske python to show me a spectrogram of both wet recordings, as that in both cases is what I want as the end result. Fig. 6 shows that there are also apparent differences in the the sound recorded as a planned end result. One thing, as is also easy to spot in the video; is that the rhythm differs. Again, that’s maybe due to me trying to make the dry monitored take sound interesting. Another thing is that the spikes are somewhat taller in the dry monitored take, meaning there is more happening in the very high frequencies. This I believe is caused because I don’t hear how the effects react to my playing, thus not affecting my playing.

CONCLUSION

I have found this very limited attempt to look into this very broad field very interesting. As stated earlier, questions regarding these matters have followed me quite some time, and having discussed it with many of my music colleagues, both performers and studio technicians, I have never thought of doing research on the field. But having learnt more about music related body motions, emotions, it has triggered me to look more into it. I believe that there is a lot more to discover in this filed, and numerous research designs to be made here. Even my limited try-outs has revealed that there is—at least for me personally—a connection between music related motions and emotions, and that the perceived sound affects ones playing and therefore also the audible end result. What would be interesting is to go deeper into different aspects of a research like this, and maybe narrow it down to different kind of effects to be used. For instance one could have blues players playing through their normal amps, with their preferred overdrive (if they use it), and then play the same part monitored directly (dry). That would maybe be a good starting point, before going to all noise guitarist taking away their monster pedalboards. In essence this is trying to find out on a broader scale what makes good recordings, that also correlates with the musicians who recorded it. We all have experienced recording some part, and when you hear it again after post processing, your comment is: «Cool … who’s playing?», haven’t we.