Shim-Sham Motion Capture

Music-related motion capture

My background and inspiration

As a research assistant for RITMO Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Rhythm, Time and Motion, I came in contact with several methods of tracking motion. I worked a bit with the Video Analysis toolbox for python, and I mentored the Music Moves: Why does music makes us move? online course for two years now, learning more and more about the world of motion tracking. Last semester I also started to work with motion-capture (mocap) data - labelling markers and gap-filling trajectories of long-ago aquired data in Qualsis - in preparation for an open source catalogue of data.

I took this course because I wanted to cement the knowledge I already had in this field and to learnt what I didn’t have the chance to yet. The online course part of this class went smoothly, the Music Moves course is interesting and for the first time I also got the chance to take the tests and get the certificate (with a final score of 97% yay). The other part of this course consisted of several classes during which we were introduced to several techniques of motion tracking and finally, the project. One of the topics I enjoyed the most was the introduction to biomechanics class, where I finally got to understand some of the underlying physical and biological principles which puzzled me before - plus, it was sciency talk which I missed terribly! I’ve learned a lot during the class on accelerometers as well, even if I didn’t use this technology in my final project, and I got to do a short study of how much I moved over time while doing planks and listening to music - besides the great workout. The video analysis class was extremely relevant for a seminar that I’ll have to hold for WoNoMute, and that’s why I didn’t focus on this technology either. Instead, I chose to do a project based on mocap data, to finally learn about the whole timeline of a project that uses an optical infrared marker based system - in this case, Optitrack.

Having been exposed to mocap in research labs before, I started to wonder how is mocap used outside of this area and for what. That’s how I thought of the entertainment world and how mocap data is used to animate 3D characters. When our teacher for the course, Tejaswinee told me about Blender, I decided to give it a go and try to animate some characters using mocap data. I was eager to try it and curious if I will enjoy it as much as I thought.

The project

My goals for this project were to learn as much as possible about the process of capturing motion in the lab using the optitrack system and have as clean of a data as possible, as well as going as far as I could with animating some characters based on the captured data. Since I wanted some music-related motion, I chose a fragment of a swing routine called Shim Sham. I decided to record three takes and later use them to animate three different characters and to perform some analysis on them - inspecting the markers and their displacement and speed.

Mocap with Optitrack in the lab

Optitrack and Qualsis are two different mocap systems, each with their ups and downs. I learned that Optitrack is much more friendly for creating skeletons and rigid bodies and this was a good plus. I couldn’t believe how straight forward was to create a predefined skeleton. We did it in class in half an hour! However, there are several factors that can influence the quality of the data - e.g., the amount of drop outs (marker trajectories) - so I was set of having as reliable of a data as possible.

The first thing I did was to spend some time preparing the room - I pushed the furniture to the walls, reangled the cameras and got rid of all reflections - so that I didn’t have to mask anything before calibration. Which was very good, no intentional blind spots. Then, when calibrating, I took extra care to calibrate the space in which the dancing was going to happen. Maximizing the capturing areas for cameras and calibrating very well, I ensured that at all times, as many markers would be seen by at least three cameras, preferably more, and it worked. Taking in consideration the sampling rate of the system, I avoided a quick song, with quick movements hard to decipher. All this extra care payed off and the recordings was really clean with very few, if any gaps!

Creating a skeleton was way easier than in Qualsis. I used a predefined skeleton for entertainemnt (since I was later going to animate it) with the baseline + 13 markers, 50 markers in total. During the first tests, I realised how important the correct placement of markers was, and I had to adjust several of their positions to align with the biomechanical constrains of a human body.

After this, recording the data was quite straightforward. Below you can see a short sneak peak from during one of the recordings. Exporting the data for anlaysis went smoothly as well.

Analysis the mocap data

After exporting the mocap data as .csv files, I analysed them with the Jupyter Notebook provided in class. However, my computer is quite old and down’t have a lot of computational power, so instead of using all the data, I only used the first 1000 rows of each of the takes, aproximately 8 seconds. In this clip you can see which dance moves were retained in the analysed data.

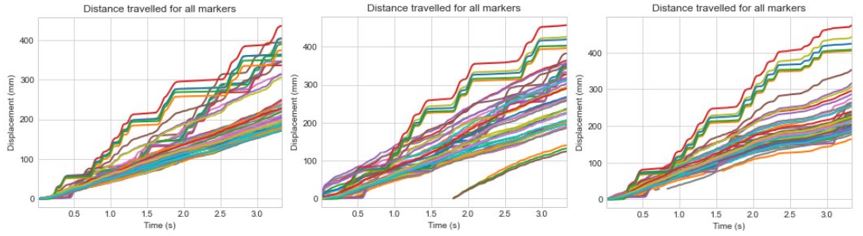

When I came up with this project idea, I was interested to see if the notion of “warming up to the groove” (as mentioned by Hans T. Zeiner-Henriksen during the 5th week on the Music Moves course, when talking about groove research) would be observed in the data. Translated to motion, I expected to see that in the second and third takes there would be more displacement than in the first one, so the dancer would move more.

In the graphs below, the distance travelled for all markers in the three takes are shown. Visually, this seems to be in line with my intuition - you can see how in the first take, the legs and feet are moving significantly more than the rest of the body, whereas in the other takes the rest of the body is starting to move more and more - especially in the graph for the first take, the legs and feet are having a significantly different curve: the curves in the upper part of the graph are for the knees, shins, ankles, and toes. I calculated the average amount of displacement along each axis for the three takes, and the values are also consistent with this idea. The dancer himself mentioned after the recording that in the second take started to focus on moving the upper body (and booty!) as well as the moves with the feet, and that in the third take he tried to focus on everything (and stumbled upon some steps). A more sistematic study (with more takes) is necessary to find a definitive answer, though.

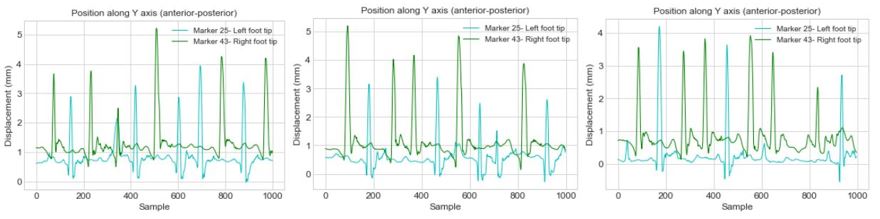

After considering the previous graphs, I was interested to see which markers had the most movement that was relevant for the performed dance move - going with the right foot in front once, then the left, then twice with the right, like in the dancing clip. Logically, the tip of the toes marker had the most movement, and also the most relevant. Here we can see the displacement of the toe tip markers positioned along the Y (posterior-anterior) axis. We can also start to notice the exact moves of the feet (and where the dancer stumbled over his steps a bit).

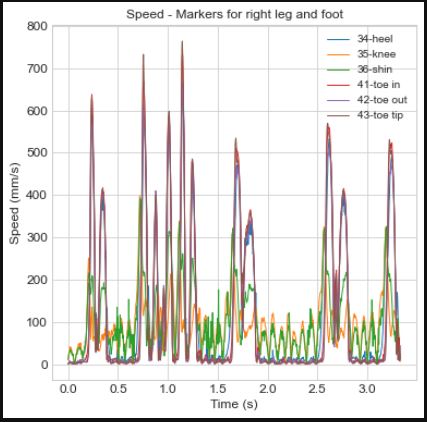

When analysing the speed of the markers I checked the trajectories for the knee, shin and ankle markers as well as for the toes, and all showed a clear indication of the dance moves. However, the markers placed on the tip of the toes gave the biggest amount of information (as expected) - you can observe this in the graph below, where all the markers of the right leg and foot in the first try are plotted.

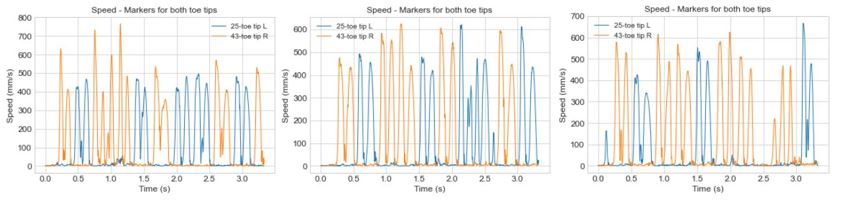

When plotting the speed of the left and right tip of toes markers for all three takes, the dance move performed becomes entirely obvious. We see two peaks for each move (speed was used to move the foot in front and again to take the foot back), and we can observe how the speed for the right and left foot differ. The mistakes become quite obvious as well (when there are more peaks than necessary for the move).

(Almost) animating mocap data in Blender

Blender is a open source 3D creation suite. And it’s exceedingly complicated, a fact I didn’t know before coming up with this project. I spent half the time watching tutorials and trying to understand how to move around the space and between modes and generally, how to use the program. I spend almost all the remaining time troubleshooting the retargeting between the mocap armature and the armature of the characters I downloaded from Sketchfab. I still had to manually add constrains for almost all bones in the final animations because of this and that reason (I don’t understand enough about this yet to explain it). Weirdly enough, the biomechanical skeleton we did in class had better results when retargeted on a stormtrooper character, than the entertainment skeleton I used for this project. I’ve learned that it’s much more complicated to retarget mocap data on characters if the armatures are not constructed of more or less the same bones - e.g., the monkey had no neck bone, which messed up the position of the head quite often. Since the presentation we had to give in class focused more on the animation part of the project, I will not give too many details here. Sufice to say that I didn’t go very far, and instead of having three cute and funny characters dancing Shim Sham in the same time, this is as far as I got… I couldn’t even figure out how to export it in a nice animation and add sound..

Final thoughts

Through this project, I had two man goals and I believe I managed to reach them both. On one hand, I wanted to learn how to go through the entire timeline of a mocap based project - from data aquisition to data analysis. This step was entirely successful - I managed to have a very clean data aquisition, and the analysis showed proof of what I intuitively believed to be true before. Arguably, I could have done a more complex analysis, and in future projects I will focus on extracting more information from the mocap data than the basics and on having better roots on existing literature. The purpose of the analysis should have also been clearer, and less exploratory, for which I apologize.

On the other hand, I wanted to challenge myself and see if I can manage to animate a character with the mocap data from the lab, and have an animated “performance”. This step was not as successful as the first, considering that I barely managed to have a somewhat okay animation with two characters. However, even being unsuccessful, this step taught me something about myself - no matter what I believed before, I now know with some amount of certainty that I would not like to work with 3D animations; it’s a fascinating world and I deveoped a huge respect for anyone who works in this field, but it’s not for me.

Overall, this course was very useful for me. There was almost no overlap with what I knew from before, but rather all my previous knowledge which was scattered around the field of motion tracking is now better cemented is theoretical knowledge and improved by the practical knowledge I gained. Thank you, Tejaswinee, for a great course and for your help and support along the way!