Bandwidth to Band Together

Abstract

The thesis evaluates approaches of remote collaboration in a contextualised setting of traditional Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) ability to facilitate collaboration, and contemporary solutions for Remote Music Collaboration Systems (RMCS). With a review of three approaches to remote collaboration, they have been evaluated by opportunities and constraints in a collaborative songwriting and mixing setting. By using a framework for categorizing DAWs utilization and usage, existing DAWs have been evaluated and contextualized with how they can transition into approaches for remote collaboration. The research has been conducted by examination of existing platforms, review of literature and previous research, personal experiences, and an experiment where approaches of remote music production have been tested with a following group interview. The results present an overview of contemporary solutions, possibilities and obstacles when conducting remote music production.

Background

In this blogpost, a brief overview of the background and results are presented. Telematic communication and collaboration have experienced a drastic increase in the last ten years have been further accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic (Vitagliano, 2021). Broader high-speed internet coverage enables professional broadcasters and consumers to use the same infrastructure and tools for distance production and collaboration. Before wide spread internet coverage, the transfer of audio and video for broadcasters has relied on expensive solutions such as satellites or telephone lines, sacrificing latency when using satellites, and quality when using telephone infrastructure. A popular term used in the broadcasting and film industry is green production, a practice aiming to reduce the production’s environmental impact. In practice, implying less movement of people or goods to a location either to send it back to a centralized location, or part of the production solved in a more environment-friendly way. Transfer of audio and video leads to new obstacles in terms of what’s the most efficient way of solving latency, data transfer, and storage. In an organized environment such as broadcast, there is little room for creative collaboration, as most actions are planned and executed. Broadcast operations contrasts how Remote Music Collaboration Software (RMCS) operates, which relies on feedback from other collaborators, often in a unorganized environment. Still, RMCSs provide a valuable testing ground to understanding remote production principles, as they exhibit the same issues with latency and data volume as professional broadcasting solutions. The thesis investigation were done with two research questions:

-

Research Question 1:What are the opportunities and constraints of three distinct collaboration approaches for users in a collective songwriting or mixing setting? Hypothesis: Each approach can be used to facilitate remote collaboration in its way, but it depends on the situation, users, task, and product desired. More than one approach is required to fulfill a end-to-end production, and several approaches must be used to obtain a finalized product.

-

Research Question 2: What affordance are there in the most used Digital Audio Workstations, and how does this affect the facilitation of remote collaboration? Hypothesis: Existing platforms are designed based on who uses the platform, and not all platforms are utilized the same way. Affordance in DAW design affects how remote collaboration can be facilitated, as producers, artists and technicians have different requirements for a platform.

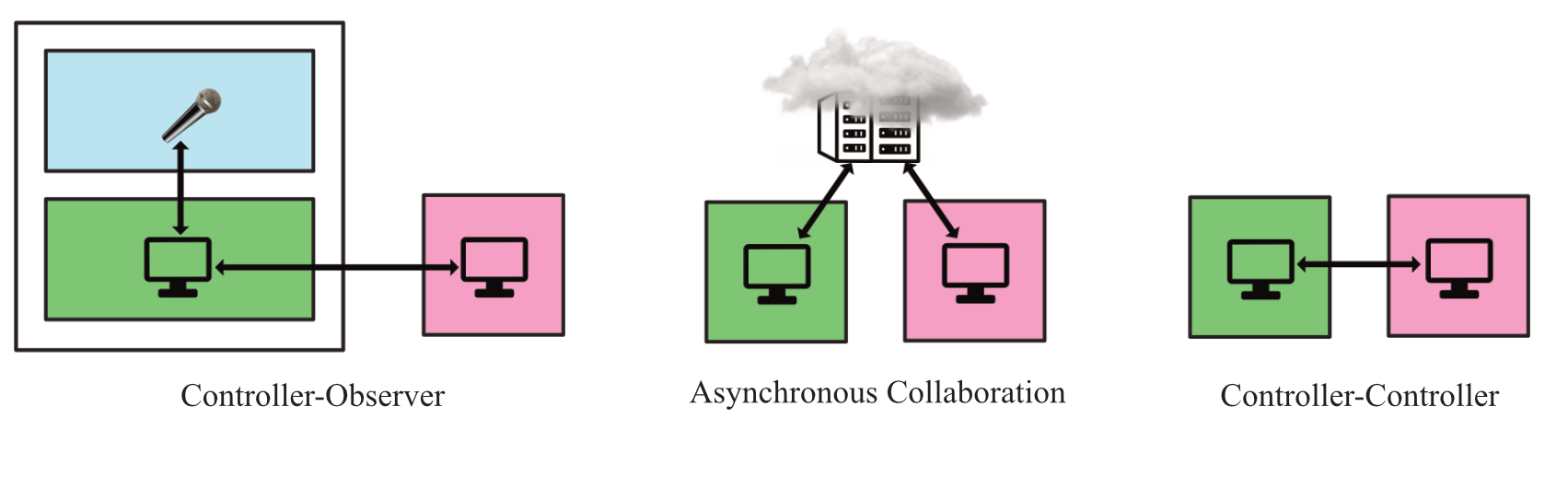

The study proposes to identify approaches used in remote collaboration of music production and songwriting as follows:

Asynchronous Approach (AA): The process of transferring files asynchronously, with limited real-time communication. It is widely used due to its flexibility, but it can face challenges with cross-platform compatibility and large file transfers. Signal-chains can be bounced together with audio, making revisions more difficult. Bandwidth limitations can also impact efficiency in projects requiring frequent revisions.

Observer Controller Approach (AC): The process of one collaborator in control over the session while the other participant(s) observe and comment in real-time. One participant (the Controller) controls the platform, while the other participant (the Observer) provides instant feedback and input. This approach is beneficial in producer-talent scenarios and can work with any platform that supports audio transmission and screen-sharing.

Controller-Controller Approach (CC): The process of participants having equal control over the session and communicating in real-time. Mltiple participants have equal control over the session simultaneously. This synchronous real-time approach eliminates the need for file exchanges and allows all participants to see and hear changes in real-time.

Together with RMCS playing an increased role in how music is created and collaborated, the DAW market offers many software alternatives, ranging from user-friendly to complex software with advanced capabilities. Some DAWs specialize in specific tasks, while others aim to provide as many features and functions as the user can imagine. Although most DAWs share the same basic layout and functionality, their tools, features, workflow, and GUI differ. According to Strachan, Cubase and Logic were initially MIDI sequencers that later added audio support in the 1990s. In contrast, Pro Tools started as a hard-drive recorder and did not implement MIDI until 1999. When Ableton and FL Studio were released in 2001, there was an expectation that a multi-functional DAW that was not reliant on hardware should include everything in the box (Strachan, p. 75-79, 2017). Pro Tools continues to follow a “retro-imitation” or “skeuomorphic” design philo- sophy based on analog hardware, given its historical foundation as a recorder (D’Errico, 2022). Pyramix, a DAW primarily used for recording and mixing in ultra-high sample rates, follows a similar process-oriented design philosophy that prioritizes functionality over aesthetics.

The study proposes to divide workstations into three categories:

-

Amateur Centric workstations are categorized as workstations with limited functionality, focused on the beginner/amateur musician or producer. They can do basic recording, editing, and producing but cannot expand into the higher level complexity needed for professional work, limiting the toolset available. For example, Bandlab offers simple creative tools for songwriting but limits the virtual instrument libraries and the number of tracks available. While these DAWs may have a different functionality than professional workstations, they can still be effective tools for those who are just starting out and learning the basics of music production. They can help beginners develop their skills and gain confidence before moving on to more complex and advanced software.

-

Artist Centric workstations are based on the creativity of the artist or producer. They often disregard the recording and mixing part of a project, and favours the production or performance process. For example, FL Studio’s sample-based workflow is centered around the sampler and sequencer, allowing for easy creation of loops and patterns. The interface is designed to be visually appealing and intuitive for creative experimentation, with a focus on step-sequencing and automation. However, FL Studio has limited recording capabilities compared to other DAWs and may not be the best choice for more traditional audio editing and mixing tasks.

-

Mix Centric workstations usually do not have any reasonable limitation in the number of tracks, busses, or plugins that the creator can apply and are generally designed to facilitate audio recording, editing, and mixing tasks, with a focus on creating polished, professional-sounding mixes. Some examples of Mix-Centric DAWs are Pro Tools, Logic Pro, and Cubase. Their primary function is to be an endpoint in the creative process - releasing recorded music or audio straight from the DAW to the desired platform or format. In general, Mix-Centric DAWs prioritize audio quality and editing/mixing capabilities over creative experimentation and linear workflows.

Dependencies in Virtual Environments

Both Olson and Olson (2000) and Spilker (2012) suggests that virtual environments does not replace a physical meetup. The participants of my study suggest that the Asynchronous and Controller-Observer approaches do not constitute as large of a difference in their workflow compared to how they would have done it physically in the same room. This aligns with what Hracs et al. (2016) discusses, with a location-agnostic approach to music production making it more accessible. Reliving the boundaries between a virtual environment and a physical environment, can provoke new modes of hybrid platforms such as Bandlab; by not emulate or imitate workflows seen in desktop platforms for music creation. If the platformization of workflows into online environments also can support a collaborative DAW, it would create a new dichotomy of how music is collaborated by supplying a collaborative environment regardless of the platform actually being used for this purpose. The collaborative function can be seen more as an add-on, rather than the primary function, breaking barriers between virtual and physical environments. The informal interactions was not measured in this study, as the participants were free to interact in-between sessions. But its clear from this study that the participants found it just as enjoyable working remotely as physical presence. This can also be of affect from their knowledge and confidence in remote environments, but it can also be the nature of the Controller-Controller approach, which incorporates both individual and collective presence. The Asynchronous- and Controller-Observer approaches does not display the same level of collaborative emergence as the Controller-Controller approach, which offers a more democratic environment than the other approaches. Roles has to be more defined to effectively collaborate in a delayed-feedback collaboration. It is clear that all approaches function as pre-distribution networks, before the finalization of a project. Both the Asynchronous and Controller-Observer approach function best before, and after the main part of the project to either initialize ideas, or to finalize them. However, to create the actual content of a project, a Controller-Controller environment is best suited, given equal participation from both collaborators is needed. The motivation to initiate remote collaboration, is determined by how engaging contributes are willing to be in the project. As shown both from the experiment and the contemporary state of collaboration platforms, they function on separate terms where it may be easier for some creators to neglect the real-time and synchronous aspect of the collaboration, to rather collaborate in a delayed-feedback environment. This can potentially ease the scariness of begive themselves into a remote collaboration. Bandlab is one example of a platform that both supports Asynchronous collaboration tools in their social network, where the same material later can be edited in a Controller-Controller environment. This hybrid may function as a ice-breaker for collaborators that would rather collaborate in a physical environments.

Collaboration Approaches vs. DAW Affordance

The study highlights an interesting dichotomy within DAWs, where certain DAWs are better suited to facilitate specific modes of collaboration than others. This finding can be attributed to the inherent design and functionality of the different types of DAWs. The Controller-Controller platforms presented in the study position themselves as Amateur- and Artist-Centric types. They are opposed to Mix-Centric workstations which can be easily adapted for Controller-Observer or Asynchronous collaboration approaches. Mix-Centric DAWs are characterized by a greater emphasis on ensuring reliability, consistency, and standardization. These dependencies, rather than enhancing the creative process, contrast Amateur- and Artist-Centric DAWs, which are designed to a more userfriendly, flexible, and conducive to experimentation and improvisation, which is also the feedback seen in the Controller-Controller approach. Even though there is a lack of Mix-Centric DAWs that support Controller-Controller approaches, it is essential to note that the transition to a Controller-Controller environment may not be an easy or immediate one. The reliance on reliability and consistency in Mix-Centric DAWs means that it will take time to establish the necessary dependencies to create a reliable system for Controller-Controller collaboration. However, as more musicians and music producers begin to recognize the benefits of this mode of collaboration, we may expect to see a gradual shift towards more userfriendly and flexible DAWs better suited to facilitating new ways of collaborating. Nevertheless, the need for a Controller-Controller environment in Mix-Centric DAWs must also be discussed, as the dependencies in those platforms are not the same as Artist-Centric or Amateur-Centric workstations. A mix- or mastering engineer may not need the same modes of collaboration, with equal participation from others in the process. Therefor a “poducer-artist” setting would be more suiting to compare with, as the “producer” in this setting is the mix- or mastering engineer, and the “artist” is the client, defined in this study as Controller-Observer approach to remote collaboration.

References

[1] Vitagliano, J. (2021). Bandlab founder meng ru kuok talks reaching 30 million users, outselling garageband and empowering music- makers around the world. Retrieved April 12, 2023, from https://americansongwriter.com/bandlab-founder-meng-ru-kuok-talks-reaching-30-millionusers-outselling-garageband-and-empowering-music-makersaround-the-world/

[2] Olson, G. M., & Olson, J. S. (2000). Distance matters. Human–computer interaction, 15(2-3), 139–178.

[3] Spilker, H. S. (2012). Piracy cultures| the network studio revisited: Becoming an artist in the age of" piracy cultures". International Journal of Communication, 6, 22.

[4] Strachan, R. (2017). Sonic technologies: Popular music, digital culture and the creative process. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

[5] D’Errico, M. (2022). Push: Software design and the cultural politics of music production. Oxford University Press.

[6] Hracs, B. J., Seman, M., & Virani, T. E. (2016). The production and consumption of music in the digital age. Routledge New York, NY.