Unsupervised Classification of Sub-Genres of Electronic Music

This thesis project is a study of unsupervised machine learning techniques for the classification and clustering of sub-genres of electronic music. New sub-genres of electronic music are frequently introduced and most have similar audio characteristics, having a proper distinction between them is a laborious task. Therefore, it becomes essential to explore tools and techniques that help us differentiate between these genres easily and efficiently. Two approaches suggested by Barreira and Rauber have been employed for the clustering of music. Barreira’s approach uses a model-based clustering technique by employing Expectation-Maximization for Gaussian Mixture Models. Whereas, the Rauber approach uses Growing Hierarchical Self Organizing Maps which is an extension of Self Organizing Maps. Moreover, Low-level audio features that mathematically show characteristics of audio are extracted for feeding into these algorithms.

Background and motivation:

Music Information retrieval (MIR) is an interdisciplinary field concerned with the development of innovative approaches to streamline the plethora of digital music and provide easy accessibility by extracting features from music (audio signal or noted music) and by developing different search and retrieval schemes. Given the importance of music in our society, it’s surprising that MIR’s research is still relatively new, having widely started around two decades ago, MIR has however undergone a transition since then. Some of the widely popular applications in music information retrieval are signal analysis, music recommendation, classification of mood and genres/sound/instruments, etc. Several clustering and classification techniques have been introduced and implemented for the classification of genres of music. Ranging from several approaches using supervised machine learning techniques (Ahmad et al., 2014; Asim & Ahmed, 2017; Bahuleyan, 2018; Tzanetakis & Cook, 2002), etc. In these techniques, the model is trained on input data that has been labeled in correspondence to a particular output. Moreover, some employ semi-supervised classification (Poria et al., 2013; Song & Zhang, 2008) approaches which are a combination of supervised and unsupervised machine learning approaches. However, these techniques necessitate manually tagged data. As a result, these approaches are restricted in their ability to evolve with new data, music, and genres, as manually constructing and updating a big dataset for machine learning models is not always viable. The unsupervised approach is a branch of machine learning in which the model is not given any labeled data to train itself, rather it autonomously works to find patterns and information, and it is not constrained to the requirements of manually tagging the data. However, just a few solutions have been presented, ranging from using hierarchical self-organizing maps(Ahmad et al., 2014), employing the Hidden Markov model (Barreira et al., 2011), or more recently using an unsupervised artificial neural network(Pelchat & Gelowitz, 2020) (Raval, 2021). Moreover, these solutions majorly explore the classification of relatively easily distinguishable genres which are widely popular like pop, hip-hop, rock, classical, etc. The elements that differentiate between them are very distinct from each other and have very less overlapping. The classification of genres that are similar to each other or have similar elements present in them has very minimal exploration, like (Quinto et al., 2017) wherein the classification of subgenres of Jazz music using deep learning techniques has been performed. Motivated by the concepts of unsupervised machine learning, audio signal processing, and feature extraction techniques, my research question became: How to efficiently implement unsupervised machine learning techniques that cluster or classify mainstream genres to different sub-genres of electronic music? and subsequently enhance and evaluate them.

System Description and Implementation:

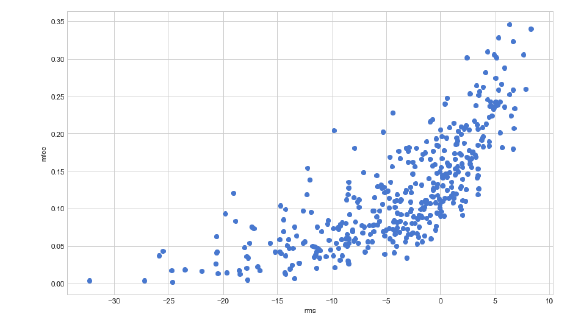

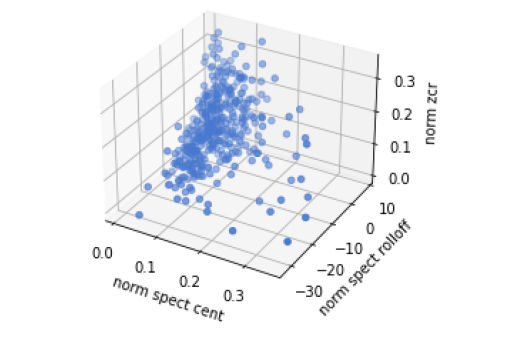

The first step in the project is the audio signal processing step, which is to extract features, these features are related to the properties of the audio sample such as spectral analysis, timbre, loudness, and melody among others. These features when extracted are large in numbers and have a large number of dimensions, therefore a feature reduction technique is required for optimizing computational time, storage space, and redundancy. But before that, a normal standardization is employed after which the features dimensionality reduction technique based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is performed. The results are then fed into two separate systems that are being implemented in this thesis. The first system as proposed by (Barreira et al., 2011) uses a model-based approach for the classification of genres. The second system uses psychoacoustic models and self-organizing maps for classification purposes and is proposed by (Rauber et al., 2002). The dataset used in this project is called MTG-Jamendo dataset (Bogdanov et al., 2019). It contains audio for 55,701 full songs, with a duration of at least 30 seconds, is in the MP3 format, and has the quality of 320kbps at the sampling rate of 44.1kHz. The tracks in the dataset are annotated with 692 tags encompassing genres, instrumentation, moods, and themes that have been applied to the music in the dataset. The sub-genres chosen for this project are: “house”, “trance”, “funk” and “minimal”. Now since there are thousands of tracks present in the electronic genre category and a few hundred in each subcategory, it becomes crucial to extract a limited amount of tracks for the testing and training of the algorithm, therefore, to save computational expenses, 100 tracks from each genre are selected randomly. All the tracks are down-sampled to 22,050 Hz and are turned into mono tracks. Finally, the full-length tracks are sliced into a duration of 30 seconds clip is taken for extracting the features and standardization of the duration. After the preprocessing, the next step as discussed above is the feature extraction. The features extracted in the project are classified into two categories, the first one is called computational features, meaning they do not represent any musical information but only describe the mathematical analysis of the. The second category is called perceptual features, these features mathematically represent musical properties based on the human hearing system. To limit the context of this project, only computational features are considered. The features extracted are, spectral centroid, spectral roll-off, spectral flux, Mel frequency cepstral coefficients, root mean square energy, and spectral bandwidth. Moreover, the spectral properties are calculated over each window of the spectrogram and a mean is taken of the calculated values to get one value for the entirety of the audio sample. Moreover, RMS energy values, along with this Mel frequency cepstral coefficients, zero-crossing rate, and power spectral value are also calculated.

Barreira’s Model-Based Approach:

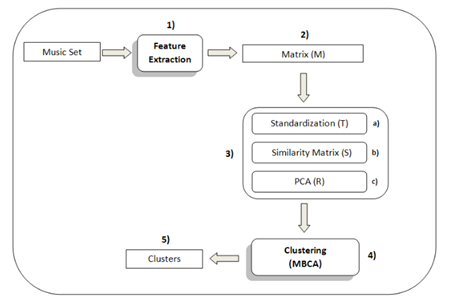

The system as proposed by (Barreira et al., 2011) uses a model-based approach for the classification of genres. In this approach, the clustering method consists of a learning approach that clusters the music samples only based on their audio features without any previous information about the genre of the samples. After extracting the above-mentioned features suggested in the (Barreira et al., 2011) approach to clustering of music, a matrix of the features concerning the audio samples is created followed by standardization and feature reduction techniques. Finally, the clustering is obtained by the Expectation-Maximization with the Gaussian mixture model algorithm. The Expectation-Maximization for Gaussian Mixture Models(EM-GMM) algorithm iteratively evaluates the parameters of a GMM. We start by taking an initial parameter set randomly, then update it by alternating between the two Expectation-Maximization stages. In other words, we first start by randomly choosing some points as the center of the clusters, then for each data point, we calculate the probability of being in each cluster, this is called as Expectation stage. Lastly, using this probability we recalculate the means and variances of the clusters this is the maximization step. We do these iterations until a convergence criterion is met.

Rauber’s Approach:

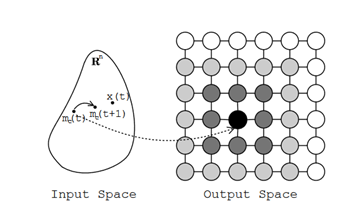

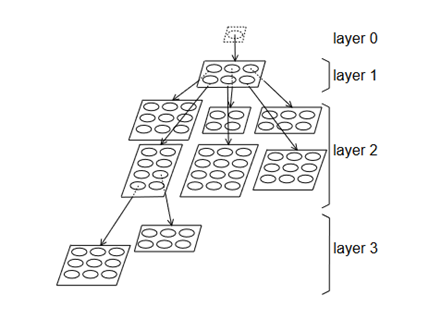

The system described by Rauber (Rauber et al., 2002) uses a widely popular neural network algorithm called Self Organizing Maps (SOM) (Kohonen & Somervuo, 1998), along with its extension called Growing Hierarchical - Self Organizing Maps (GHSOM). It is a model in which by placing related data items next to one another on a map display, the neural network does cluster analysis. The GHSOM, in particular, is capable of recognizing hierarchical correlations in data and so generates a hierarchy of maps depicting distinct musical genres into which the pieces of music are arranged. SOM is used in clustering and mapping (or dimensionality reduction) techniques to map multidimensional data onto lower-dimensional data, making it easier to grasp complicated situations. It essentially does cluster analysis by projecting the data space onto a two-dimensional map space in such a way that related data items on the map are close to each other.

The Growing Hierarchical Self-Organizing map (GH-SOM) is based on the usage of a hierarchical structure with numerous levels, each of which includes a collection of separate Self-Organizing Maps (SOMs). At the top of the hierarchy, one SOM is utilized. A SOM might be added to the next tier of the hierarchy for each unit in this map. This approach is replicated with the GHSOM’s third and subsequent levels

The figure has one map in layer 1 consisting of 3×2 units and It gives a rough arrangement of the input data’s key clusters. The second layer’s six separate maps provide a more thorough look at the data. To offer adequate input data representation, two units from one of the second-layer maps were further enlarged into third-layer maps. As a result, comparable data can be discovered on surrounding map boundaries in the hierarchy

Results and Future Work:

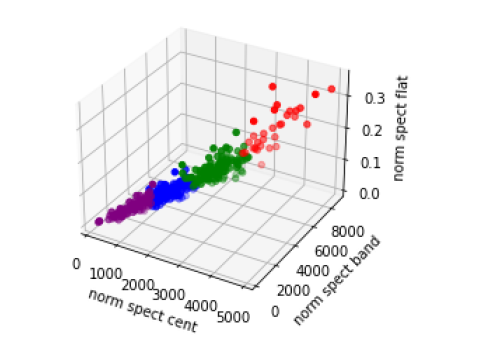

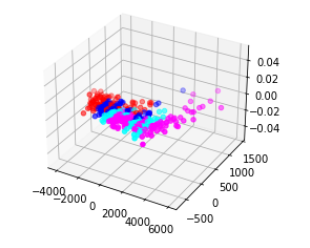

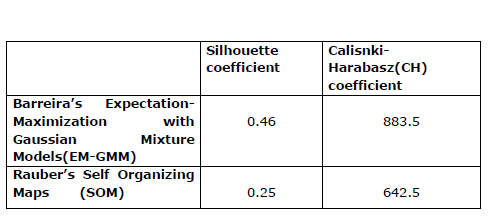

The evaluation is done based on two metrics Silhouette coefficient and the Calisnki-Harabasz coefficient. The silhouette coefficient is defined in the interval [−1, 1] for each example in the data set. When it is close to zero means that the points are uniformly distributed throughout the Euclidian space, negative values indicate that the clusters are mixed and overlapped and positive values indicate high separation between the clusters. Calisnki-Harabasz coefficient is the variance ratio criteria, often known as CH, and is a metric based on the premise that clusters that are compact and well-spaced from one another are desirable clusters. The result obtained by the models can be seen in the figure and the table given below

With limited prior knowledge of machine learning and audio signal processing techniques, the core challenge of the project was to thoroughly understand the algorithms and audio features so that an optimum implementation can be achieved. With only one semester to conduct the research, these difficulties were magnified, resulting in several technical and methodological compromises. Although both the techniques were successful to a large extent in the classification of the given four different types of sub-genres of electronic music. It should be noted that the dataset fed into the system was still quite small and the approaches for future work, need to be tested on larger datasets with more data points as well as a greater number of subgenres of electronic music. Additionally, hyperparameter tuning and optimization are highly required to make the models and algorithms robust and perform even better. Moreover, applying them to sub-genres of other popular genres like Classical, Jazz, Rock, etc can also yield interesting results. Redesigning the approaches so that they can be deployed and migrated in a real-life application should be seen as an aspect of future development. Such that they can be used in distinct Music Information Retrieval concepts like a song retrieval system based on genres, or for building a personalized music recommendation system.

References

Ahmad, A. N., Sekhar, C., & Yashkar, A. (2014). Music Genre Classification Using Music Information Retrieval and Self Organizing Maps. In M. Pant, K. Deep, A. Nagar, & J. C. Bansal (Eds.), Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Soft Computing for Problem Solving (pp. 625–634). Springer India. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-1768-8_55 Asim, M., & Ahmed, Z. (2017). Automatic Music Genres Classification using Machine Learning. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 8(8). https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2017.080844 Bahuleyan, H. (2018). Music Genre Classification using Machine Learning Techniques. ArXiv:1804.01149 [Cs, Eess]. http://arxiv.org/abs/1804.01149 Barreira, L., Cavaco, S., & da Silva, J. F. (2011). Unsupervised Music Genre Classification with a Model-Based Approach. In L. Antunes & H. S. Pinto (Eds.), Progress in Artificial Intelligence (pp. 268–281). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-24769-9_20 Bogdanov, D., Won, M., Tovstogan, P., Porter, A., & Serra, X. (2019). The MTG-Jamendo dataset for automatic music tagging. Dittenbach, M., Merkl, D., & Rauber, A. (2000). The growing hierarchical self-organizing map. Proceedings of the IEEE-INNS-ENNS International Joint Conference on Neural Networks. IJCNN 2000. Neural Computing: New Challenges and Perspectives for the New Millennium, 6, 15–19 vol.6. https://doi.org/10.1109/IJCNN.2000.859366 Kohonen, T., & Somervuo, P. (1998). Self-organizing maps of symbol strings. Neurocomputing, 21(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-2312(98)00031-9 Pelchat, N., & Gelowitz, C. M. (2020). Neural Network Music Genre Classification. Canadian Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering, 43(3), 170–173. https://doi.org/10.1109/CJECE.2020.2970144 Poria, S., Gelbukh, A., Hussain, A., Bandyopadhyay, S., & Howard, N. (2013). Music Genre Classification: A Semi-supervised Approach. In J. A. Carrasco-Ochoa, J. F. Martínez-Trinidad, J. S. Rodríguez, & G. S. di Baja (Eds.), Pattern Recognition (pp. 254–263). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-38989-4_26 Quinto, R. J. M., Atienza, R. O., & Tiglao, N. M. C. (2017). Jazz music sub-genre classification using deep learning. TENCON 2017 - 2017 IEEE Region 10 Conference, 3111–3116. https://doi.org/10.1109/TENCON.2017.8228396 Rauber, A., Pampalk, E., & Merkl, D. (2002). Using Psycho-Acoustic Models and Self-Organizing Maps to Create a Hierarchical Structuring of Music by Musical Styles. Raval, M. (2021). MUSIC GENRE CLASSIFICATION USING NEURAL NETWORKS. International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Science, 12(5), 12–18. https://doi.org/10.26483/ijarcs.v12i5.6771 Song, Y., & Zhang, C. (2008). Content-Based Information Fusion for Semi-Supervised Music Genre Classification. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, 10(1), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2007.911305 Tzanetakis, G., & Cook, P. (2002). Musical genre classification of audio signals. IEEE Transactions on Speech and Audio Processing, 10(5), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSA.2002.800560