The Algorithmic Composition Explorer

Algorithmic composition has a long and rich history, and encompasses a wide range of approaches and techniques. It can been defined simply (and quite broadly!) as the application of formal rules to generate musical material and ideas.

While it is a well known tool for creating new music and ideas, it can also be a valuable approach in teaching music and composition. Being able to describe music in terms of algorithms can contribute to a learners understanding, helping focus their attention on the structure and organisation of that music. The application of algorithmic thinking to music can be used to understand form and style. And algorithmic composition can be used as a vehicle for concept development, with the algorithms producing raw material that is then edited and assigned musical meaning by the learner.

My plan was to build an interactive system for learning about algorithmic composition with the following aims:

- Take a “learning through practice” approach, allowing users to manipulate and compare different algorithmic approaches, offering a visual representation of the generated music as well as audio playback.

- Allow users to take away their generated musical ideas in the form of MIDI scores and downloadable music notation.

- Use ubiquitous, standards-compliant technologies that allow it to have the greatest reach, while requiring little previous technical knowledge on the part of the user.

- Make the code open-source and ready to be built upon with more algorithms, export formats, and visual representations of the music.

As one of the aims is to open up the world of algorithmic composition to those with little technical knowledge, it is important to convey that it is not necessary to be a accomplished programmer or have an advanced understanding of mathematics in order to apply algorithmic thinking and techniques to composition. There are many historical and contemporary algorithmic composition techniques that do not require the use of a computer, and these are no less interesting for it!

What is Algorithmic Composition?

In the 1680s, Leibniz argued that the rules for composition are so well defined that anyone can be instructed to compose following certain rule sets. Cope (2015) goes so far to say that all composers use algorithms while composing whether they are aware of doing so or not - “all composers are algorithmic composers” (Cope, 2015).

If we are all, consciously or subconsciously, composing with algorithms, it would make sense that there would be almost as many different approaches to algorithmic composition as there are composers, and that classifying them into “methods” or “schools of thought” is going to be a difficult undertaking. An algorithm can be a complete approach to composing a piece of music, but more commonly a hybrid approach is taken, with algorithmic music being composed using a combination of multiple different methods.

Aleatoric methods involve the use of chance or randomness. Mozarts Musikalisches Wuerfelspiel is an early example of using chance, an approach adopted and developed by composers such as John Cage in the twentieth century. For true aleatoric methods, the probability of any event happening is the same for all events - there is no preference for one result over another.

Then there are the methods which use probability. Xenakis was a pioneer here with an approach he called stochastic music, which involves the use of randomness together with statistical principles (Aschauer, 2008). Unlike purely aleatoric methods, stochastic methods allow for more control over the output while still working with random data.

Rules-based methods and constraint systems allow the application of certain rules to musical material. These rules can be widely applicable, covering general music theory models such as counterpoint and voice leading, or more targeted and focused towards a specific idea or intention, depending on composers musical goal.

Then there are algorithms that use machine learning and systems that work with fractals. There are genetic algorithms which take a biologically inspired approach to composition. Then there are cellular automata, chaotic systems and game of life algorithms, and many, many more. It was beginning to feel like I had bitten off more than I could chew!

Building the Algorithmic Composition Explorer

As explained above, the three main criteria for the Algorithmic Composition Explorer were:

- To be widely available and requiring little in the way of previous technical knowledge. Avoiding the need for any installation or setup to get started.

- To allow users to experiment with and compare different algorithmic approaches, and offers a visual representation of the generated music as well as audio playback. Allowing users to take the generated music with them and incorporate it into their own work.

- To provide a platform that can be built upon and extended with new algorithms, instruments and components.

If the goal is to build something widely available, building for the Web is a good option. There’s nothing to install or configure - you just need a browser. It works across devices - a responsively designed website can (in theory!) work as well on a phone as on a desktop. And the Web offers a lot of potential for building an Algorithmic Composition Explorer with the Web APIs for audio and MIDI. Tone.js is a great example of a library that is built on top of the Web Audio API and, in addition to lots of sound generating loveliness, offers global transport and sequencing options which make it suitable for working with algorithmic composition. But before I could jump into the details, I needed a bit of structure and the ability to modularise the code. I ended up going with static site generator Jekyll, as it offered enough flexility while still keeping things simple. To make sure the app worked as well on mobile devices as on desktops, I employed the responsive talents of the CSS framework Bootstrap.

Regarding the algorithms themselves, I wanted to use examples that were straightforward enough for learners to get an understanding of simply by adjusting parameters and figuring out what’s going on under the hood. The learning-through-practice approach is about designing the system so that it provides intrinsic feedback - in this case, demonstrating a clear relationship between the changing of an algorithms parameter and the results that are heard. Any instructions provided should encourage exploration and ask questions, as apposed to simply explaining what an algorithm is doing.

With all of this in mind, starting at the beginning made sense here. Guido of Arezzo’s vowel-to-pitch algorithm is one of the earliest known, dating back to the 11th century. And while simple to comprehend, adds an interesting relationship between the source text and music produced.

Mozarts Musikalisches Würfelspiel was an algorithm that was almost discounted, due to the lack of control the user has over the music produced. However, it is a good example of using randomness to generate music, and could encourage the learner to think about form and style, and what makes the song sections work together.

Like Mozarts dice game, the Markov chains algorithm also works with previously prepared music, but the algorithm itself is more complex in this instance. The underlying concept is understandable however, and much can be learned about this algorithm simply by varying the source material and adjusting the order.

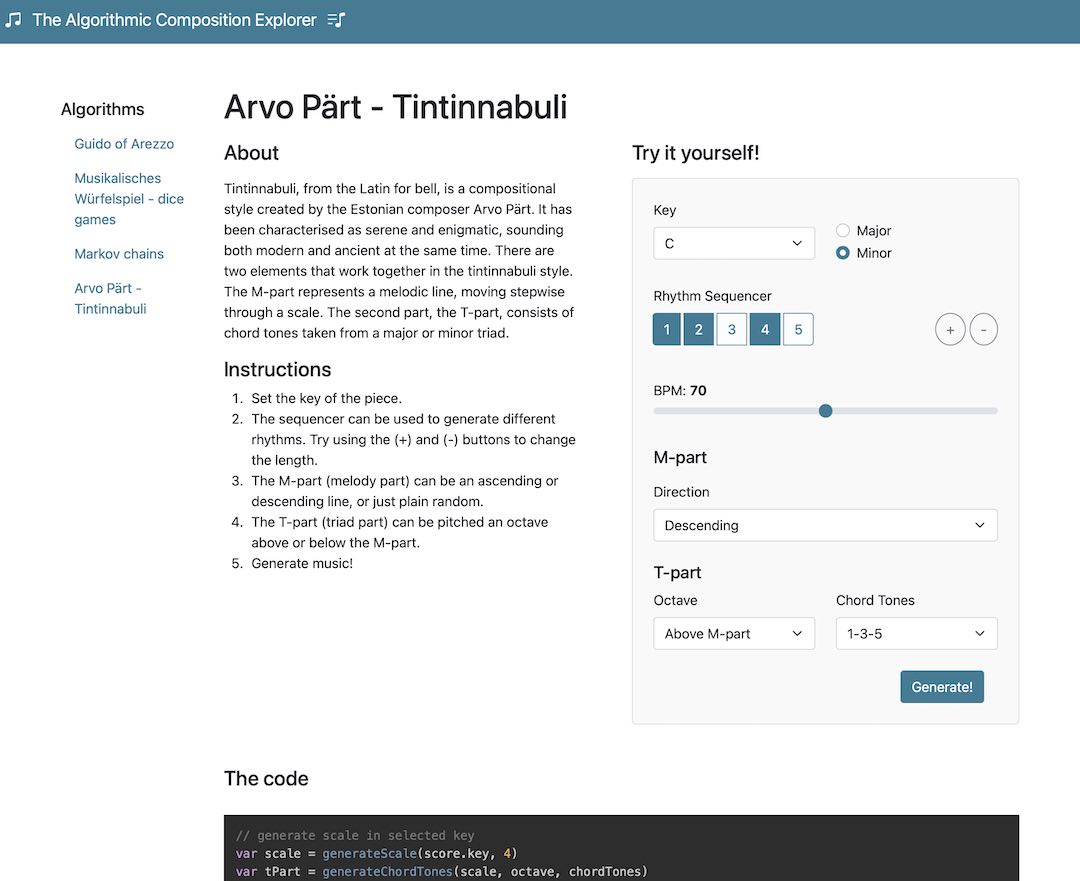

Arvo Pärt’s Tintinnabuli takes a step back from Markov chains in terms of the complexity of the algorithm, but opens up a world of exploration. While this is an approach that can be more easily grasped, the results are more customisable and potentially more easily transferable to the learners own compositions.

In addition to the algorithms themselves, an audio player and some sort of notation viewer was needed to be able to listen to and visualise the music generated. I used Tone.js for sequencing the generated music, as well as for creating a couple of instruments - a sample-based piano and a synth - that could be used for playback. ABC.js was used for displaying the music notation.

Finally, in order to get music in and out of the app, importers/exporters were written for ABC notation and MIDI files.

Conclusion & future work

The end result of all this work can be found at The Algorhthmic Composition Explorer.

Due to the limited timeframe of this thesis, there are many aspects of the software I would have liked to have developed further. Implementing more algorithms is perhaps an obvious one. Cellular Automata could be an interesting algorithm to tackle next. There are also many improvements that could be made to the existing algorithms. For example, allowing the user to upload songs to the Markov Chains algorithm, or even being able to populate the Musikalisches Würfelspiel grid with user-created phrases.

Adding MIDI functionality could be an interesting area to explore. Being able to input notes using a MIDI controller would be a great way to feed the Markov Chains algorithm with data, or add phrases to Musikalisches Würfelspiel.

Regarding the rendering of notation using ABC.js, there is definitely room for improvement! It works, but the flexibility of an alternative like VexFlow could make for more accurate notation.

During development I found myself wanting to take ideas generated and incorporate them into my own compositions. This lead to several brainstorming sessions where I explored how to adapt the system more for this purpose. I have spoken much about the modularisation of the code, but this is an approach that would be interesting to take with the interface as well. Creating a ‘playground’, where different algorithmic components can be combined in order to build a customised algorithm without the need for coding would be an interesting next step. In some ways, this could be seen as moving the focus away from learning about different algorithmic composition approaches and more towards creating an environment for algorithmic composition itself. This thesis has very much been focused on the learning through practice approach, and I believe learners could only benefit from more opportunities to do just that.

My hope is that the Algorithmic Composition Explorer creates a spark for people curious about this fascinating subject, helping them realise the creative potential of the application of algorithms in creating new musical ideas, and inspiring them to dig deeper.

Check out the app here: https://algorithmic-composition-explorer.com.

For those that want to contribute, the source code can be found on Github.

References

- Cope, D. (2015). Algorithmic Music Composition. In G. Nierhaus (Ed.), Patterns of Intuition (pp. 405–416). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9561-6_19

- Aschauer, D. (2008). Algorithmic composition [Thesis]. https://repositum.tuwien.at/handle/20.500.12708/11036