Gatekeepers by design? Gender HCI for Audio and Music Hardware

Abstract

Hardware for audio and music is subject to inscribed social processes and can bring them to appearance through visual cues and language. This dissertation investigates how established hardware for audio and music can communicate issues related to gender. In particular, it looks into (1) how language of live interfaces in music can inform about whether and how gender shapes musical tools; and (2) to what extent can gender bias in the design of musical interfaces be detected through visual cues. With a mixed methods approach, this thesis aims to create a richer picture on potential gender identities in hardware for music. Two studies are presented: an interview analysis with expert women from music technology and a quantitative study on gender reception of audio and music hardware. The findings and results suggest that gender perception for established hardware in audio and music exists. To follow up, design recommendations are proposed on how to approach the development of interfaces under the notion of pluralism. This implicates to involve people with different backgrounds in musical hardware and DMI design processes, with implications for academia and industry in order to make musical hardware more accessible.

Problem Space

Whether academic or industrial, the music technology field is known as a field that needs more gender diversity (Frid, 2019; Gadir, 2017; Xambó, 2018). People from various cultural and economic backgrounds, ethnicities, gender identities and diverse abilities are little represented (Frid, 2019) when designing audio and music hardware. The question is to what extent are these circumstances reflected in the language of musical live interfaces, the visual semantics of music technological artefacts and in its interaction design (ID)?

In a narrow sense, a hardware can be, according to Magnusson and Mendieta (2007), a computer, a soundcard, controllers and sensors. Although there has been a vivid development in instrument design with electric components in the last two decades (Bongers, 2000), the look of the interfaces that are available to the mass market usually have very similar shapes, dominated by edgy forms and knob type controllers (Jensenius and Voldsund, 2012). Susann Vihma adheres in “On Design Semiotics” (Vihma, 2010) that entire cultures can be recognised on the basis of its product environment, as humans are capable of constructing meaning through the form of artefacts. Different academic disciplines have ascertained that artefacts communicate non-verbalized human values (Berg and Lie, 1995; MacKenzie and Wajcman, 1999; Vihma, 2010).

Research Questions

This research aims to contribute to a critical reflection of current technological practises in the field of digital music instrument design. Informed by my previous research (Jawad and Xambó, 2020), the focus of this investigation is to enquire the following main research question: To what extent established hardware for audio and music can communicate issues related to gender? This main research question is tackled by the following two research sub-questions:

- How can language of live interfaces in music inform about whether and how gender shapes musical tools?

- To what extent can gender bias in the design of musical interfaces be detected through visual cues?

Background

Gendered Artefacts in Music Technology?

According to Lucas, Ortiz, and Schroeder (2019), in commercial DMI production the product designers would often encapsulate the goals, behaviours and abilities of a broad target user group into a fictional archetype known as persona when designing DMIs. This approach implicates that commercial forces bypass large parts of the population. MacKenzie and Wajcman (1999) wrote that technologies can be designed, consciously or unconsciously, to open certain social options and close others. Particular design features up to entire technologies can be and act politically (MacKenzie and Wajcman, 1999). Therefore, music technology and musical instruments, like any other technology, do as well act as cultural and symbolic artefacts that absorb political content around access to, respectively, physical ability, gender, socio-economic status, class and cultural hierarchies (Morreale et al., 2020; Zeiner-Henriksen, 2014).

Gender HCI – Inspiring Approaches

Barth (2012) considered the current interface trends as predominantly biased towards male users as they have been considered the ’default’ gender in computing for decades. Gender HCI (Cassell, 2002) or feminist HCI (Bardzell, 2010) established in the last decade under the influence of HCI, design research (Demirbilek and Sener, 2003), STS, gender studies and psychology. This approach is a tool to deconstruct how gender identities shape the design and use of technological items (Bardzell, 2010). For example examined Livingstone (1992) the ratings of participants that were asked to assign a symbolic gender to domestic technologies in brown goods (e.g. TV components, stereos and PCs) and in white goods (e.g. kitchen and laundry appliances). Brown goods were be male biased while white goods were female biased. According to Rode (2011), Fiesler, Morrison, and Bruckman (2016), and Light (1999), technologies that are femininely gendered, however, gradually lose their status as technology. Another inspiration for the survey design was given by Demirbilek and Sener (2003), who theoretically investigated how “meaning” could be designed into a product in order to “communicate” with the user at an emotional level. Finally the research that has been undertaken around gendered software design by Vorvoreanu et al. (2019) showed that:

“(…) software cannot be made “better” by having a “pink” version and a “blue” version (…) to improve software’s usability across genders, software needs inclusivity across the cognitive diversity that arises not only among different genders, but also within them.” (Vorvoreanu et al., 2019, p.11)

Mixed Methods

In particular, the two research sub-questions are addressed with a mixed methods approach (Lazar, 2017) of combining qualitative and quantitative research methods. According to Adams, Lunt, and Cairns (2008), using mixed methods is helpful for understanding how technology is subjectively and collectively experienced and perceived by different user groups. Beyond that, mixed methods can provide a balanced reflection of an issue. It will give a more differentiated account on the objectives as mixed methods serve both to gain deep insights from experts in one field and to contrast their impressions with a wide range of experiences The participants of both the interviews and the online survey share overall similar backgrounds and interests.

Method 1 – Interview Analysis

The first research sub-question has been addressed by means of analysing the interviews with women experts in the field of musical interface design, music technology research and artistic practise. Through initial exploration, different thematic patterns emerged that could potentially be explored. However, the most profound thematic cluster emerged when analysing statements in relation to music technology and engineering. We could analyse that the language of music technology, especially the term ‘music technology’ in academia carries ideas of activities that are stereotypically gendered.

Method 2 – Online Survey

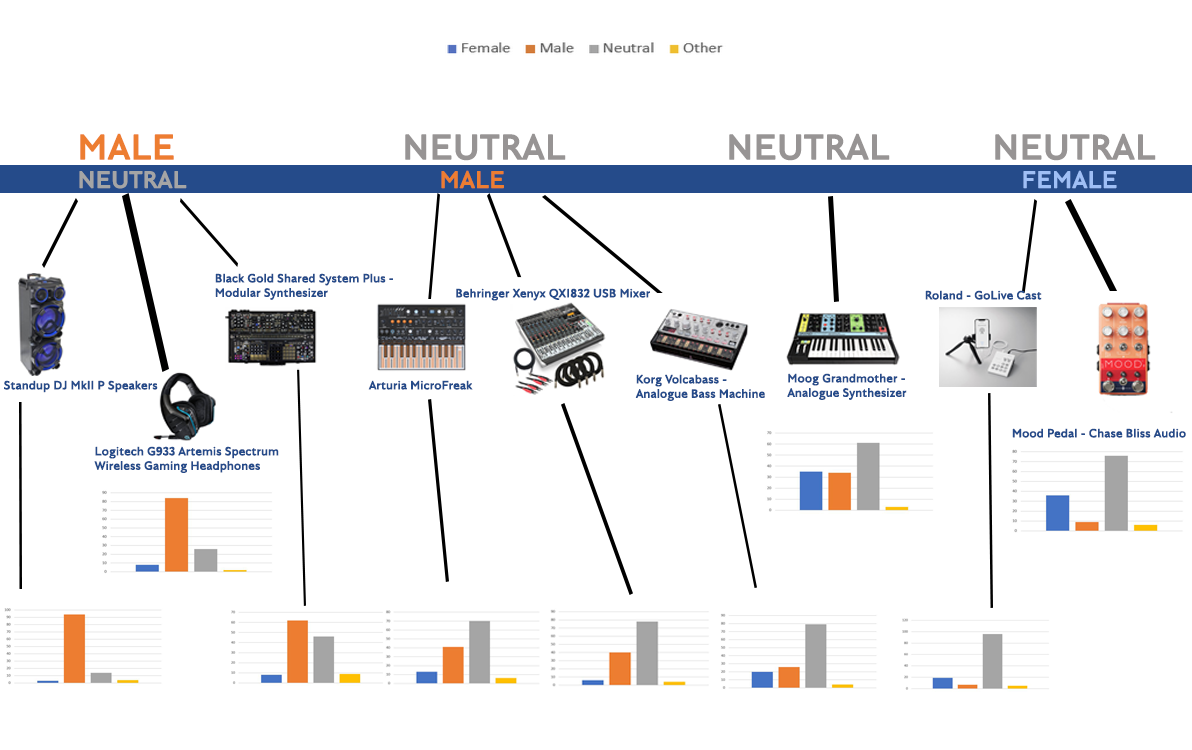

This study investigates the gender perception of hardware in music and audio. Hundred and eleven participants took part in an online survey with questions on colour, shape and wording of 9 exemplary artefacts of music hardware. In this study, the results of the responses are introduced and discussed. The gender assignments and intensities of the attributes for the respective instruments were briefly outlined. Three instruments were chosen for in-depth analysis with the aim at representing a ‘male’ instrument, a ‘neutral’ instrument and a ‘neutral - female’ instrument. It has been shown that there is a tendency to perceive most of the items as neutral and/or male as to observe in Figure 1.

In the gender assignments there were differences occurring among the gender groups, but they were of minor degrees.

Discussion & Final Remarks

Universal, Pluralistic or Neutral interfaces?

As noted in Oost (2003), many objects and artefacts designed for “everyone” without a specific user group in mind are based, often unconsciously, on a one-sided user image. This could possibly be reflected in its semantics. Colour, shape, form and texture of the designed objects are sent as messages that are part of our language structures that deal with meaning, as Demirbilek and Sener (2003) explain. These attributes would communicate with users and can therefore never be contextually neutral. Vorvoreanu et al. (2019) stress, while leaning on Bardzell (2010), that attention to individual differences within genders can be emphasised by the notion of pluralism rather than universality. Approaching the design of interfaces could support individual differences and non-binary notions of gender identification, which can embrace also other underrepresented groups.

References

Barth, Derrick Ryan (2012). “Designing the Gender-Neutral User Experience”.Worcester, MA, USA:Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

Berg, Anne-Jorunn and Merete Lie (1995). “Feminism and Constructivism: Do Artifacts Have Gender?” In: Science, Technology, & Human Values 20.3, pp. 332–351.

Bongers, Bert (2000). Physical Interfaces in the Electronic Arts. URL: https://bertbon.home.xs4all.nl/downloads/IRCAM.pdf.

Frid, Emma (2019). “Diverse Sounds: Enabling Inclusive Sonic Interaction”. PhD thesis. Stockholm, Sweden: KTH Royal Institute of Technology

Gadir, Tami (2017). “Forty-Seven DJs, Four Women: Meritocracy, Talent, and Postfeminist Politics”. In: Dancecult 9.1.

Jawad, Karolina and Anna Xambó (2020). “How to Talk of Music Technology: An Interview Analysis Study of Live Interfaces for Music Performance among Expert Women”. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Live Interfaces, pp. 41–47.

Jensenius, Alexander Refsum and Arve Voldsund (2012). “The Music Ball Project: Concept, Design, Development, Performance”. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression.

Lazar, Jonathan (2017). Research Methods in Human Computer Interaction. 2nd edition. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier.

Light, Jennifer S. (1999). “When ComputersWereWomen”. In: Technology and Culture 40.3, pp. 455–483.

Livingstone, Sonia (1992). “The Meaning of Domestic Technologies”. In: Consuming Technologies: Media and Information in Domestic Spaces. Ed. by Eric Hirsch and Roger Silverstone. London, UK: Routledge, pp. 113–130.

Lucas, Alex Michael, Miguel Ortiz, and Franziska Schroeder (2019). “Bespoke Design for Inclusive Music: The Challenges of Evaluation”. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression. Porto Alegre, Brazil: UFRGS, pp. 105–109.

MacKenzie, Donald A. and Judy Wajcman, eds. (1999). The Social Shaping of Technology. 2nd edition. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Vihma, Susann (2010). “On Design Semiotics”. In: MEI Objects & Communication (30–31), pp. 197–208.

Vorvoreanu, Mihaela et al. (2019). “From Gender Biases to Gender-Inclusive Design: An Empirical Investigation”. In: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’19. Glasgow, Scotland, UK:ACMPress, pp. 1–14.

Xambó, Anna (2018). “Who Are theWomen Authors in NIME?—Improving Gender Balance in NIME Research”. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression. Blacksburg, Virginia, USA, pp. 174–177.

Zeiner-Henriksen, Hans T. (2014). “Old Instruments, New Agendas: The Chemical Brothers and the ARP 2600”. In: Dancecult 6.1, pp. 26–40.