Harmonic interaction for monophonic instruments through musical phrase to scale recognition

Abstract

This thesis introduces a novel approach for the augmentation of acoustic instruments by providing musicians playing monophonic instruments the ability to produce and control the harmonic outcome of their performance. This approach is integrated into an interactive music system that tracks the notes played by the instrument, analyzes an improvised melodic phrase, and identifies the harmonic environment in which the phrase is played. This information is then used as the input of a sound generating module which generates harmonic textures in accordance with the identified scale. At the heart of the system is an algorithm designed to identify a scale from the played musical phrase. The computation relies on established music theory and is based on musical parameters retrieved from the performed melodic phrase. A database of audio recordings comprised of improvised phrases played by several saxophonists is used to test the algorithm. The results of the evaluation process indicate that the algorithm is reliable, and it can consistently recognize the scale of an improvised melody conveyed by a live musician. This discovery led to the exploration of the affordance to influence accompanying harmony by a monophonic line and integrating the phrase-to-scale match algorithm within an interactive system for music-making. By interacting and playing with the system using a repurposed controller mounted on the saxophone, performance strategies and practical ways are offered to play, modify, and further develop the system.

Introduction

In my thesis I present a novel approach for controlling harmony, sometimes referred to as the “vertical” aspect of music, with its “horizontal” aspect, the melodic line. The suggested approach includes a software application, an algorithm, and a method for repurposing a video game controller, to track the pitch of a saxophone, capture and analyze an improvised musical phrase, determine the scale of the phrase, and use that output for music generation in an interactive manner.

Recent advances in the field of music production, and the technology available for anyone who wishes to produce music by electronic means, have enabled a wave of artists to develop a personal sound, produce their own music, invent instruments or write code to serve their artistic needs and aesthetics. Musicians are now able to invent and customize music applications to further their artistic research and remain original and inventive. Machine learning algorithms allow the musician of today to interact and play with artificial intelligence models with a great deal of communication and musical expression. The use of technology, in combination with traditional acoustic musical instruments in a wide range of musical genres, is becoming mainstream. Technological developments like the loop-pedal, the harmonizer effect, various instrument augmentation projects, and the invention of the electronic wind instrument controller, have helped the saxophone to maintain its place as one of the most popular instruments across musical genres. These advancements help it to remain at the forefront of bridging technology with acoustic musical instruments.

Instrumentalists in general, but more specifically, saxophonists, face several limitations when it comes to using technology when playing, whether it is performing a concert, recording in a studio, or practicing at home. The saxophone, for example, cannot be muted in a considerable way without affecting the timbre quality or the overall experience of playing the instrument, unlike the electric guitar or the trumpet. A key challenge for saxophonists employing technology in a performance setting is the operation of additional devices, controllers, or interfaces while playing. They experience limited spare bandwidth since playing the saxophone requires using both hands, almost all fingers and the mouth. The solution for this is usually using foot-pedals or using the hands during musical pauses.

From a personal perspective, playing the saxophone for over three decades, and being involved with performing improvised music for the past 20 years, I found myself in search of ways that will allow for harmonic control. The saxophone is a monophonic wind instrument capable of producing only one note at a time (disregarding advance Multiphonics techniques), and since note sustain and tone quality are determined by the length of the air stream and the physical combination of the instrument and player, this can be seen as limiting at times. I found that playing or controlling harmony by using additional devices can be quite tricky when considering both the limited physical bandwidth and the attention required. My motivation when approaching this thesis was to develop a tool for woodwind players that will enable monophonic instruments to control or play harmony and, at the same time, that would ‘feel natural,’ be intuitive and promote creativity.

Research question and objectives

Motivated by the concept of controlling the harmonic output of an interactive music system with the melodic output of an improvised line, as well as identifying the lack of, and thus the need for a system that grants this type of interactivity, my research question becomes: Can a system and an algorithm be developed to successfully identify the scale of a musical phrase for collective music generation? By reflecting upon this question, my objectives were realized accordingly:

- Developing and evaluating an algorithm that will successfully identify the scale of an improvised musical phrase played by a monophonic wind instrument.

- Creating a database containing improvised phrases by several saxophone players in different keys and scales for evaluating the algorithm.

- Integrating the scale recognition algorithm in a real-time interactive music system available to users and developers as free and open-source software.

- Developing, exploring, and presenting a practical way to play and interact with the system.

Contribution and system overview

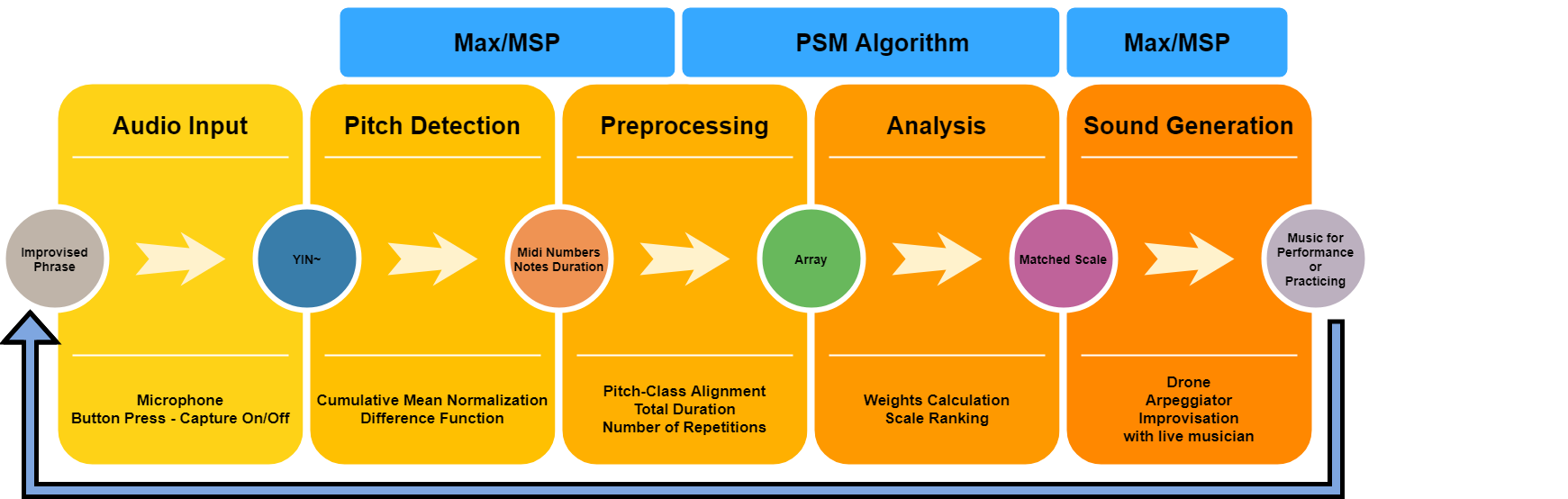

The thesis contribution primarily stands on the development of the Phrase to Scale Match (PSM) Algorithm. This algorithm analyzes a monophonic musical phrase of any length and outputs an estimated scale name that matches the input phrase from a dataset of 21 common scales. The algorithm calculates a matching scale based on several variables like the number of note repetitions, note duration, and other changeable weight-increasing factors for characteristic scale notes and note recurrences. Furthermore, a comprehensive system is presented for handling audio input, detecting pitch, analyzing a musical phrase, and appropriating a retro game controller to be used as a control interface together with two sound generating modules. In the proposed system, the data flows through the following submodules:

- Analog to digital conversion of the microphone signal, which captures the musician’s improvised phrase

- Pitch tracking module

- Buffer capturing the performed notes, including controls allowing the musician to start and terminate the capturing process

- Scale recognition module, based on the method presented in this thesis

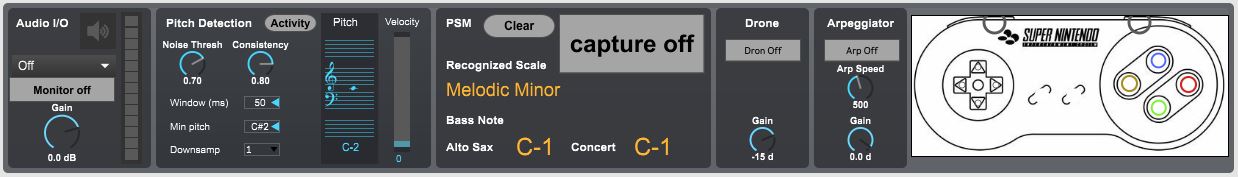

- Musical applications using the output of the recognition module (drone and arpeggiator in the current version) The proposed system and the scale recognition algorithm presented in this thesis offers a way to track the notes of a musical phrase, analyze it, calculate the tonality and scale, and output the result to several applications for music generation. The users can manipulate parameters of the system via a dedicated controller that is attached to the saxophone. The user interface (Figure 1) provides visual feedback of the audio input, detected notes, matched scale, bass note and pressed buttons of the controller.

The system was developed in Max/MSP/Jitter environment (commonly referred to as Max), a visual programming language for music and multimedia by software company Cycling ’74. Max was chosen due to its flexibility for creating interactive music systems, the capability to generate audio and the ability to integrate other programming languages within its environment. The PSM algorithm part of the system is written in the JavaScript programming language since the procedural operations required to identify the scale are too difficult to implement using Max objects by themselves.

The Phrase to Scale Match (PSM) algorithm

The proposed algorithm takes an improvised monophonic musical phrase and matches it to a musical scale from a scale-dataset of 21 scales. For the algorithm to successfully identify the scale to which the improvised phrase belongs, two conditions must be met. First, the first note of the musical phrase must begin with the bass note (1st degree) of the scale. Second, the improvised phrase must be based on one scale only.

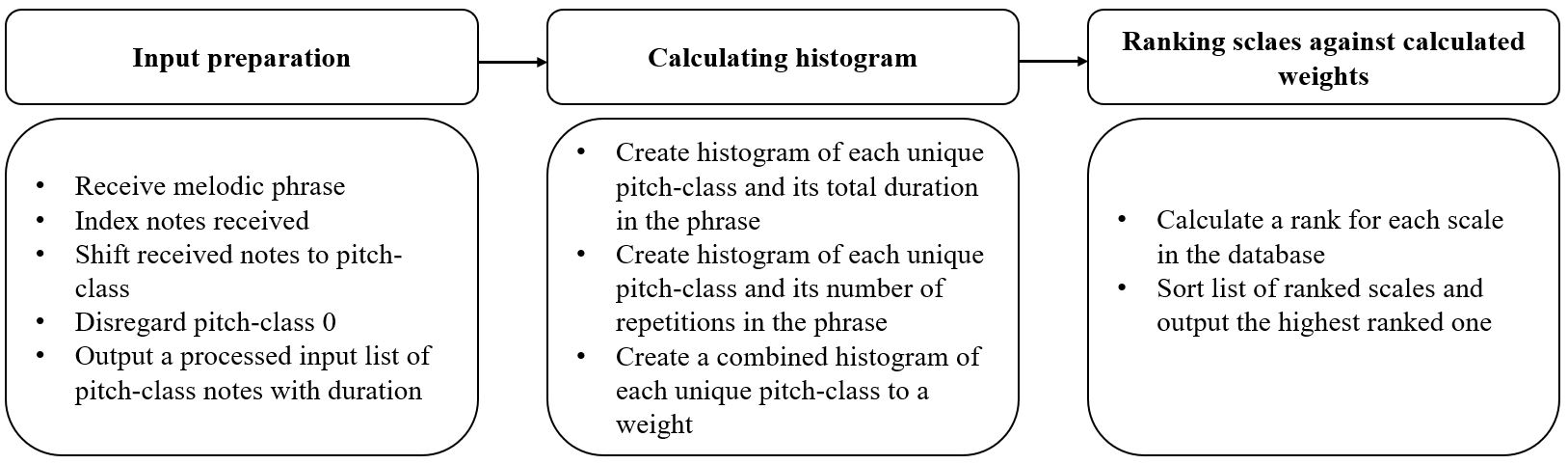

The PSM algorithm is comprised of 3 parts:

- Aligning the input notes, so that they are all in the same octave, and are relative to the first degree.

- Generating a histogram of the aligned notes played in the phrase, where each note is assigned a weight indicating its importance and impact.

- Comparing the histogram against a scale-dataset, calculating a rank for each scale, and selecting the one presenting the highest-ranked score.

Game controller adaptation

A retro-like Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) controller is used as the user-interface of the system, similar to the one in Figure 18 . The Max hi object allows for obtaining data from human interface devices. The Nintendo USB gamepad features 12 momentary push buttons, and was chosen because its shape fits well on top of the low B and Bb key-guard of the saxophone, as visible in Figure 19, and also because it allows for easy access with the right-hand which is employed less than the left-hand when playing the sax. The adoption of the SNES controller is inspired by one of the principles of Perry R. Cook on redesigning computer music controllers: ”funny is often much better than serious.” A Nintendo controller illustration has been added to the GUI of the system together with an overlaying buttons layer to provide visual feedback when pressing the buttons.

Music Generation Modules

The JavaScript object outputs a scale name based on the analysis done by the PSM algorithm. This information can now be used in various ways for interactive music generation. At the moment, two music generating modules have been developed to give an example to the kind of opportunities the system offers.

Drone Module

In this module, the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 7th degrees of the output scale are extracted to form what is known as a “seventh chord”. The notes of the chord are converted from pitch-class notes to midi integers based on the key of the phrase, and then frequencies. The four frequencies, representing the four notes, are played by four sinusoidal oscillators with randomized amplitude in different time points and lengths. This creates a drone effect where the chord is continuously playing while offering a changing harmonic texture. A Rotary knob allows for controlling the gain output of the Drone module. The player can continue improvising on the scale until deciding to feed the algorithm with a new harmonic environment by pressing the Capture On/Off button again.

Arpeggiator Module

The Arpeggio module is like the Drone module, but this case, all seven degrees of the output scale are converted to frequencies and are randomly played over three octaves with bell sounds. The notes are panned back and forth to play between the left and right channels (ping-pong effect); two rotary knobs allow for controlling the speed of the arpeggiator and the volume. The speed knobs of the arpeggiator and the option to set the step size of the speed buttons (by increments of 10, ranging between 10-100) are mapped to the controller’s D-Pad in this way: up – faster, down – slower, right – decrease step size, left – increase step size.

A combination of the Drone and the Arpeggiator module gives a very subtle harmonic textural background for a performer to play and improvise over. This can also serve as a practicing tool to exercise scales and improvisation. By creating a randomized melody, the bell-like notes can also serve as a melodic inspiration for the improviser, though this interaction only goes one way. More examples of additional interaction opportunities this system can offer are discussed under the future work section.

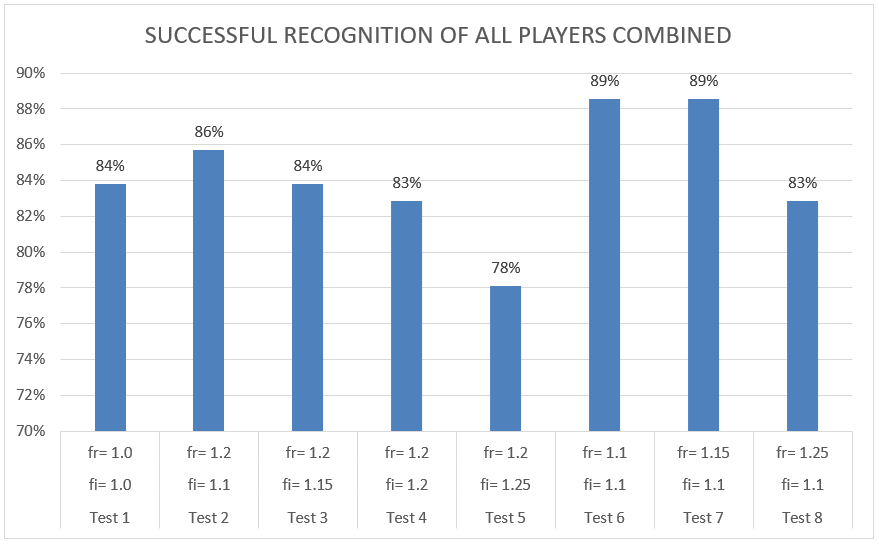

Evaluation

105 phrases were tested against the algorithm, or 21 phrases (in 21 scales) times five players. The entire database was pushed into the algorithm a total of eight times with different sets of factor (fi, fr) values. The results are plotted in a graph (Figure 23), comparing the success rate of the eight tests. In test 1, the fi and fr values were set to 1.0, meaning no weight increase was applied. The success rate in test 1 is 84%. Tests 6 and 7 represent the highest success rate (89%) when tested with fi =1.1 and fr=1.1/1.15. The result of test 1 tells us the algorithm itself, without giving any increased weight to indicator notes or repetitive notes, already have a high success rate (an average of 17.6 phrases recognized correctly out of 21 per player). When reviewing the results in Figure 23, we can also establish that increasing the success rate can be achieved by setting very small fi and fr values. In test 5, where the increased factor values were higher in comparison to the other tests (fi =1.25 and fr=1.2), the success rate showed poor results (78%).

It is important to discuss several crucial points when coming to evaluate the algorithm with the current database. First, we should keep in mind that improvised musical phrases can be seen (or heard) in a very subjective way, where one player can consider a phrase in one scale while another player can consider the same phrase in a different scale. The perception of phrases and their scales can differ substantially from one player to another. The PSM algorithm is, in a way, a deterministic algorithm, attending a subjective or an individual problem. Second, tuning (of pitch) affects the algorithm’s prediction. Several of the recorded phrases begin with a bent note or contain untuned notes throughout the phrase. A bent note at the beginning of a phrase means that the bass note of the phrase is being identified incorrectly by the pitch tracker, consequently swaying the phrase prediction. Phrases containing untuned notes will always be recognized falsely, and changing the weight factors will not affect their prediction outcome. As an example, in Table 8, player 1 holds a success rate of 95% in all tests, where 20 out of 21 phrases were recognized correctly. When inspecting the results, we can see that the Mixolydian scale was the one scale mistakenly recognized in all tests of player 1. This might suggest that there is a problem with the phrase itself and not necessarily with the algorithm. These kinds of database discrepancies make it difficult to evaluate the PSM algorithm and essentially mean that a larger and more accurate database is required for evaluation (See “future work” for additional reflections regarding a database).

Playing with the system

A way to evaluate the system can also be by playing with it and develop musical approaches to advance its potential. This kind of evaluation comes from personal reflections after I was able to experiment with the system. I would also recommend the reader to see the attached demonstration video and listen to the musical examples in it.

By playing with the system in my rehearsal room, I have noticed that sound is bleeding back from the speakers into the microphone, creating false detection of notes and, eventually, scale outcome. My solution was to use two microphones, one, a condenser mic with low gain for pitch tracking, and the second, a dynamic mic for the acoustic sound of the saxophone. This solution significantly reduced the false detection of pitch and scales. I was standing directly in front of the speakers, which also contributed to the bleeding; therefore, for live performance, I would recommend standing behind the speakers and using headphones for monitoring. In any case, it is essential to be able to clearly hear the auditory output of the system to enhance creativity.

Just like with any musical instrument, device, or controller, mastering requires mastery. Getting used to the controller requires time and practice, but after several hours of playing, my fingers were able to find the buttons instantaneously and without much searching and looking. Another concept that was a bit more difficult to grasp and one that will require more rehearsing is the concept of controlling the harmony by just playing the saxophone. This affordance is new to me, and it is one I have never experienced before. When talking about musical expression with new human-computer interfaces, Dobrian and Koppelman, (2006) state that to reach a level of sophistication achieved by major artists in other specialties like jazz or classical music, it is necessary to encourage further “dedicated participation by virtuosi” to utilize existing virtuosity and develop new virtuosity. A skillful musician with great technical skill and harmonic knowledge, and one that holds an advanced level of virtuosity, will undoubtedly be able to play with the system and benefit from this new affordance of controlling harmonic textures by playing melodic phrases.

From an artistic standpoint, it is exciting and inspiring to play with the system. The long chordal Drone sounds, in combination with the rhythmic notes played by the arpeggiator, provide a subtle and comforting harmonic environment that allows for relaxed and intuitive improvisation. The system is responsive enough that I was able to communicate a scale with both short and long phrases. I was able to identify both correct and false scale matches of the system by looking at the UI on the computer screen and by hearing the sonic output of the system. This situation of staring at the computer screen is not ideal and is addressed in the future work section. While improvising, there were several instances in which the system recognized a different scale than what I communicated or intended to. This can happen due to noise, sound bleeding, or simply wrong playing on my part. I view those instances as a musical challenge and an opportunity to change the harmonic direction of the piece, just as if I would when playing with a live musician. I experimented playing with the Drone and Arpeggiator, both together and separately, and was able to achieve diverse musical textures that provoked different kinds of playing on my side.

Some performance strategies that I have developed by playing with the system over this short period are:

- Less is more – build the performance by adding and interacting with each sound generating module at a time.

- Keep in mind that it is possible to start a piece by playing the saxophone first and letting the sound modules join after, or by letting the sound modules play first and joining them after.

- It is sometimes hard to remember that the system can detect a scale with only a few notes. There is no need to play a lot to convey a scale, and certainly no need to play all the notes in scale order.

- By setting different speeds, the arpeggiator module provides three kinds of textural material: temporal, melodic, and harmonic. It is easier to play and interact with slower tempos, while rapid tempos can be perceived as harmony to the human ear. Experiment and employ all possibilities.

- In the current implementation, the system recognizes the scale of a phrase in reference to the first note of the phrase (the bass note). This forces the player to always start the phrase with the bass note, and it is a condition that can be somewhat limiting. A way to evade this is by starting to play a phrase from any note the player wishes to, and only press the capture button before playing the intended bass note of the scale. In this way, the listener will hear a phrase starting on one note, but the system will start capturing the phrase from a different note.

Conclusion

To conclude, the work presented in this thesis successfully addresses my original research question. The algorithm is able to recognize the scale of a musical phrase with high accuracy, and the system offers the musician the ability to influence the harmonic output by merely playing an improvised phrase. The degree of randomization applied to the sound generating modules creates the impression of several entities collectively generating music and sharing the creative control, in almost the same manner as a group of live musicians would do. The outcome of this thesis provides musicians playing monophonic instruments a novel way to communicate harmony to a machine, in such a way that other algorithms and applications can use this information to contribute to the musician-driven sonic creative process.

The implementation of the system is available for users and developers as free and open-source software. I invite you all to check it out here.