Playlist Data and Recommendations Using Artificial Neural Networks

Concept

The usage of playlists on music streaming platforms, such as Spotify, has become an effective outlet for artists to be showcased to build their fanbases. But with the over-saturation of artists trying to build their fanbases, many do not know which curators would suit them best promotion.With the trend of music listening gravitating towards these platforms, several music-focused businesses, such as radio stations and music discovery sites, have begun keeping their audience base and relevancy by curating regularly updated playlists of songs, featured in their respective shows, on Spotify. I will be discussing a machine-learning algorithm that pairs songs by independent artists, trying to gain a reputable fanbase ,with Non-Spotify curated playlists that best fit their musical profiles based on Spotify’s organization of musical attributes.

Data Mining

I initially utilized a platform called Chartmetric which provides insights into the top playlists on Spotify. Upon further investigation, I discovered many of the most popular playlists were used by artists who wanted higher streaming numbers would turn to these playlists and pay for their songs to be featured. Many of these playlists seemed to be streaming bots, and not real people. I decided to explore more consistently established and reputable sources when trying to showcase music to a broader audience. This led me to explore playlists created and curated by popular music stations, music magazines, and similar sources, well known to avid music listeners for the discovery of new releases.

Extraction of Features

The criteria for the playlist I used in my initial dataset consisted of the following: a focus on independent artists, a following of over 20,000, around 100 songs, regularly updated (additions in the past month), and mostly new releases all from the past month. Once the five playlists were chosen, I then processed the playlist in the Spotify Playlist Analyzer, an online tool that extracts data from Spotify playlists using the Spotify Web API and can convert the data into a CSV file. I used the Spotify Playlist Analyzer because I wanted to work with easily accessible data, particularly for playlists that are updated regularly, perhaps even daily. The analyzer extracts the musical attributes calculated by Spotify for various factors in the audio with scores of 1-100. These factors include Happiness, Danceability, Energy, Acoustic-ness, Instrumental-ness, Liveliness, and Speechiness. The analyzer also extracts other musical data such as Tempo, Key, and Length, Genre, and Parent Genre. I extracted unwanted columns and gave each song a label based on their respective playlist.

The labels for the playlist are as follows: 0 - Indie Pop / Rock Playlist | BIRP! April 2024 1 - Songpickr 2024 - Best New Americana, Alt Country, Folk, Blues, Retro Soul, Rock Music 2 - Pigeons & Planes 3 - UKF Drum And Bass 4 -Future House 2024

Tokenizing Parent Genres Labels

I decided on the MinMax Scaler Method over the Standard Scaler as the normalization technique. The MinMax Scaler is more suitable for algorithms, like ANNs, that require features to lie on a similar scale and performs the best on classifying problems (Raju 2020). I also performed Principal Component Analysis (PCA), the most popular form of dimensionality reduction which retains a lot of the variance in the data more compatible with the neural network (Sorzano). The scaler and PCA processing was done before concatenating this data with the tokenized data of the Parent Genres. Tokenized data, while a numeric value, does not hold value in the way the musical attribute data does and therefore could cause problems. This is also the reason why I decided not to go with the pipeline in this model because these two kinds of arrays must be kept separate before the dimensionality reduction process.

Tokenizing Parent Genres Labels

As I wanted to use the associated parent genres as a feature as well I had to tokenize each type of Parent genre and assign them a number so that they could have a numeric value that would be compatible with the numpy array. After this process, I concatenated the two arrays with different data types so that the data was finally ready for processing. I then extracted the label data and split the dataset for training and validation

The Model

Once the playlist data was extracted and labeled in this way I was able to start with the formation of the machine learning algorithm. For the classification process, I decided to employ an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) as my model of choice. I went with the High-Level API integrated into TensorFlow, known as Keras API, because of its user-friendly interface that provides easy-to-use tools to make the process of creating a neural network efficient.

Softmax Layer and Probability

The reason for this decision was the ability of ANNs to analyze the data after the softmax layer in TensorFlow. The softmax layer normalizes the scores and shows us the probabilities for each outcome. This provides not only a single label, for the best fitting playlist, but also the probabilities the machine learning model gave to the other labels, which could be useful to artist wanting to submit to multiple playlists. ##

ReLU

I experimented with the different kinds of activation layers to see if I got different results. Ultimately I found that an input layer with a rectified linear units (ReLU) activation plus two hidden layers with ReLU activations yielded the best results. ReLU function is the most used and best activation function for deep learning tasks (Krishnamuthy 2024). When I ran the model, the default Adam optimizer yielded the best results for my model.

Results

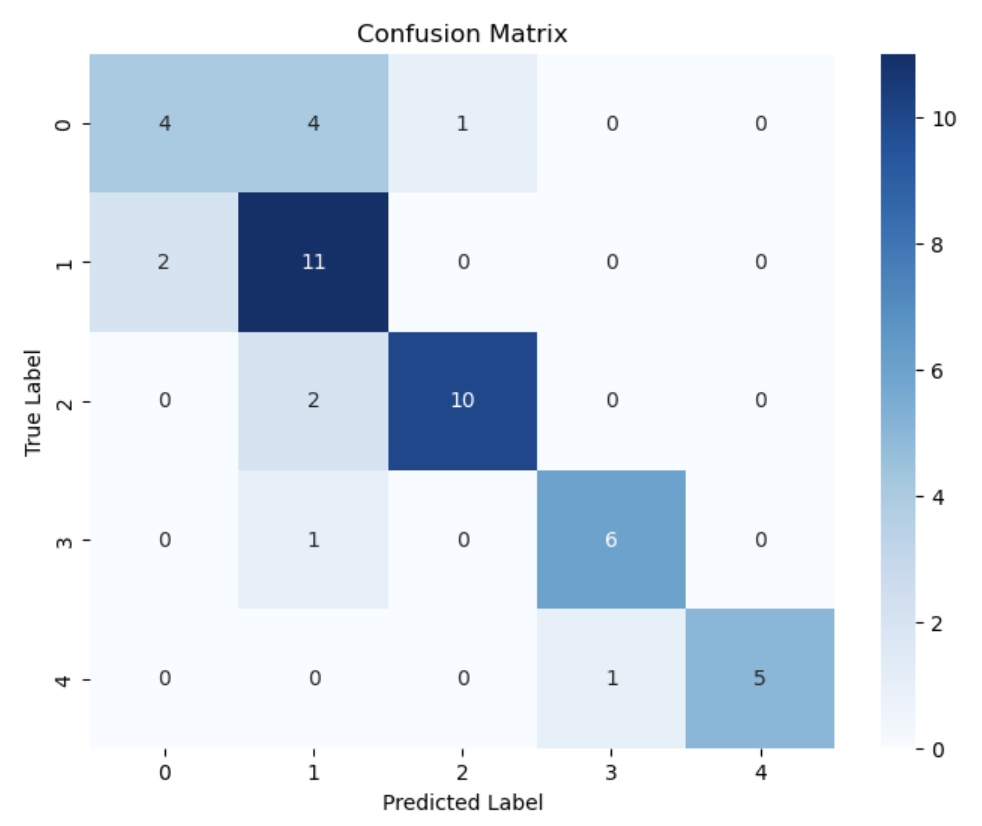

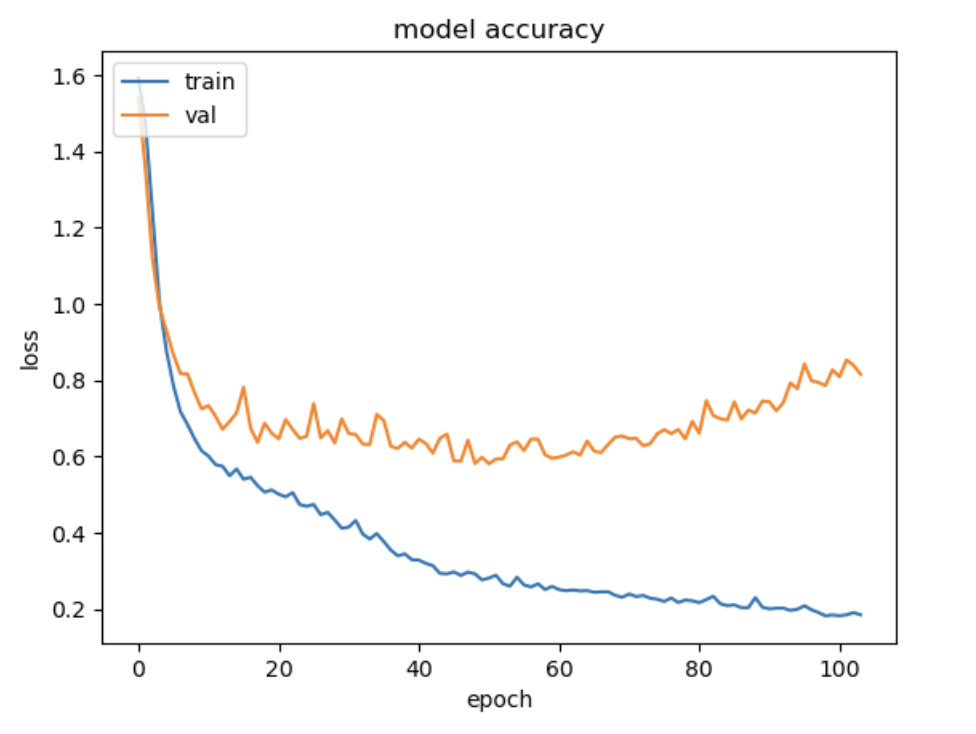

For analysis of the machine model, I used multiple tools to understand what was happening as I continued my process. I examined the test accuracy score as well as the F1 score to tune the parameters as well as the model accuracy chart to examine how many epochs the model went through before termination. I also used the confusion matrix to examine which classes were mostly being confused with another. The average test loss for this model over 5 tests was 1.098 telling us that there is room for improvement of the accuracy of the model.

The average test Accuracy score was 0.732 as well as the average F1 Score was 0.731. Since this dataset is pretty evenly distributed, I didn’t expect a huge difference between the accuracy score and the F1 score. The model accuracy charts show the validation curve diverging from the training curve, suggesting some overfitting when it comes to the training data.

The majority of the misclassified data for the first two similarly focused playlists were from each other. For the “Birp!” Playlist, 19 of the 40 misclassified songs had a True Label of SongPicker. Songpicker had a total of 29 misclassified songs and 25 of these songs were that of the “Birp!” playlist. The Pigeons and Planes playlist also had a majority of 15 out of 25 mislabeled songs that have a true label of SongPickr. Unsurprisingly, the same trend was found with the two majority Electronic Playlists. The UKF playlist had a majority of 9 out of 13 songs mislabeled as Future House, and the misclassified files of the Future House playlists were exclusively labeled as UKF. This checks out as songs in the UKF Playlist were almost exclusively within 1 number away from 174 or 84 bpm. In looking at this chart, I also note that the playlist “Birp!” has an almost equally varied group of misclassified files when it comes to those that do not belong in the SongPickr Playlist suggesting that the “Birp!” playlist is more varied in the metrics of the features we use in this model.#

Conclusion

This model provides us with a framework that does not do the job for the curator but rather makes the process easier on both ends of the curating process. This, however, is still a limited view of the song data and must be coupled with the work it takes a curator to complete their work. We must also keep in mind other unexplored factors such as song order in the playlist itself which could affect exposure. Overall, this project has offered insight into creating machine learning models that work with people and not in place of people and how that can provide those, who aim to share their music with potential fans, some help along the way.

Bibliography

Aguiar, Luis. “Platforms, Promotion, and Product Discovery: Evidence from Spotify Playlists.” Working Paper. Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2018. http://www.nber.org/papers/w24713.

Ajay, Muktha Sai. “Introduction to Artificial Neural Networks.” Introduction to Artificial Neural Networks (blog), May 29, 2020. https://towardsdatascience.com/introduction-to-artificial-neural-networks-ac338f4154e5.

Elite Data Science “Overfitting in Machine Learning: What It Is and How to Prevent It,” July 6, 2022. https://elitedatascience.com/overfitting-in-machine-learning.

H. Good, “The new gatekeepers: searching for bias in Spotify’s curated playlists”. Macquarie University, 17-Oct-2022 [Online]. Available: https://figshare.mq.edu.au/articles/thesis/The_new_gatekeepers_searching_for_bias_in_Spotify_s_curated_playlists/21343314/1. [Accessed: 29-Apr-2024]

Krishnamurthy, Bharath. “An Introduction to the ReLU Activation Function,” February 26, 2024. https://builtin.com/machine-learning/relu-activation-function.

Kumawat, Dinesh. “7 Types of Activation Functions in Neural Network,” August 22, 2019. https://www.analyticssteps.com/blogs/7-types-activation-functions-neural-network.

Raju, V N Ganapathi, K Prasanna Lakshmi, Vinod Mahesh Jain, Archana Kalidindi, and V Padma. “Study the Influence of Normalization/Transformation Process on the Accuracy of Supervised Classification.” In 2020 Third International Conference on Smart Systems and Inventive Technology (ICSSIT), 729–35, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSSIT48917.2020.9214160.

Sanderson, Grant. “What Is Backpropagation Really Doing?” 3Blue1Brown (blog), November 2, 2017. https://www.3blue1brown.com/lessons/backpropagation#title.

Siles, Ignacio, Andrés Segura-Castillo, Mónica Sancho, and Ricardo Solís-Quesada. “Genres as Social Affect: Cultivating Moods and Emotions through Playlists on Spotify.” Social Media + Society 5, no. 2 (2019): 2056305119847514. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119847514.

Sorzano, C. O. S., J. Vargas, and A. Pascual Montano. “A Survey of Dimensionality Reduction Techniques,” 2014.