The Chiptransformer

Early to mid 1980s game consoles and home computers often included a sound chip that could produce a few basic waveforms, like pulses and sawtooths. The style of music that emerged from this period is often referred to as chip music. The Chiptransformer is an attempt at building a machine learning model using the transformer architecture to generate music based on a dataset of Nintendo NES music.

The transformer is a machine learning architecture commonly used in language processing. While not particularly intuitive to understand, transformers have a number of interesting characteristics and possibilities that I was curious to explore. In particular I wanted to try some ideas concerning the data representation and the ability of the transformer to make sense of musical data. I’ll first give a short overview of how transformers work, and then talk about what I wanted to accomplish.

Transformer attention

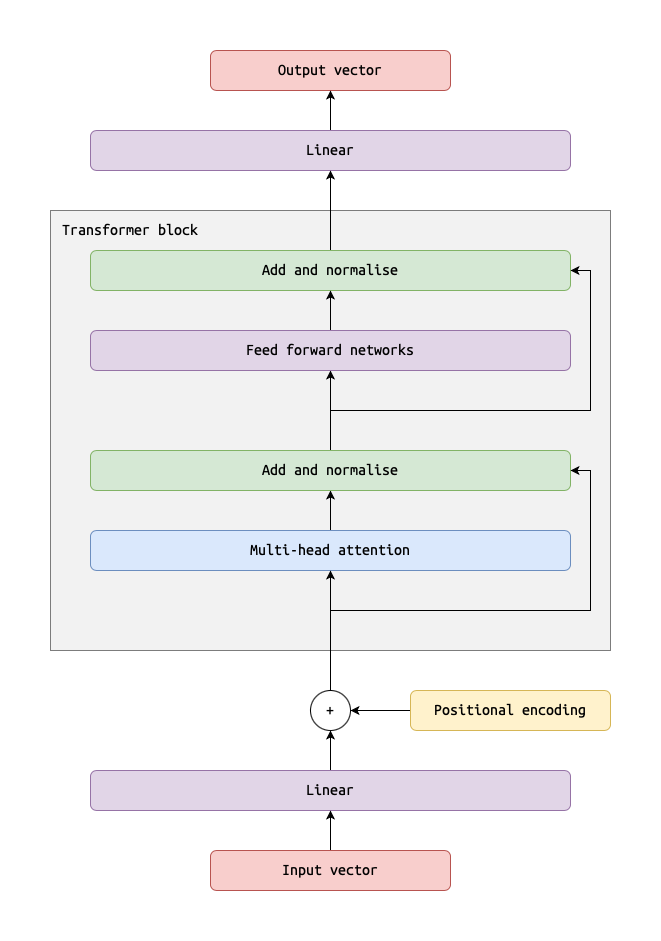

Transformers do not process sequences step-by-step like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) do. Instead, they read and process whole sequences all at once. The way transformers model relationships between items in the sequence is called attention. Attention roughly works by creating a table of similarity scores between each item pair in the sequence. The important part is that the transformer in this way can look for patterns at many different levels of abstraction in the sequences and encode those patterns using attention.

Positional encoding

Furthermore, transformers don’t actually know the order in which items are supposed to occur. To give the transformer this information, we create positional encodings, which are often sine and cosine values for different frequencies, and then add these to the vector values of each item. This means that the item vectors will have unique values based on their position in the sequence.

Encoders and decoders

Transformers first got their name because they were used for translation, by transforming a sequence into another via an encoder-decoder structure. However, for sequence generation we need only a single transformer block, called a decoder. This takes a sequence as input, and then produces an output sequence which is identical to the input sequence, only shifted one position. The important part here is that each item vector needs to keep all the contextual information from the preceding sequence of items that the model thinks is important. Therefore these vectors need to be fairly big, since there is potentially a lot of information that they need to keep track of. To make predictions then, we first need to look at the last item of the output, then place that item back at the end of our input sequence, and then run the prediction machine again.

The NES music database

So why did I choose game music from the NES? Firstly, I thought it would make some things a bit simpler. I wanted to generate polyphonic music, but I also wanted to keep the complexity low. There are many datasets available for classical music, but I was afraid they would be too complex. The NES on the other hand has only three voices for melodies and one noise channel for drums. Furthermore, old game music tends to be very structured, with simple rhythms and repeating melodies, which should make it easier to distill some general patterns from the data. Second, having grown up in the 1980s and 90s I also have a soft spot for this kind of music. It often reminds me of having fun with old computers in my childhood.

Note pitch representation

The first idea I wanted to try was using regression rather than classification. Transformers normally use something called tokens as inputs, which are simply categorical values. For the transformer to make sense of this data, tokens pass through an embedding layer, which converts each token into a vector with a lot of dimensions. The reason is that these vectors need to reflect all the contextual relationships between the tokens. With categorical input and output, prediction is also a classification task. However, I think it would be a good idea to use the numerical information we have if we encode the pitch, onset time and duration as numerical values. Therefore, I decided to make my transformer use continuous input and output rather than tokens, which meant prediction would become a regression task rather than a classification task.

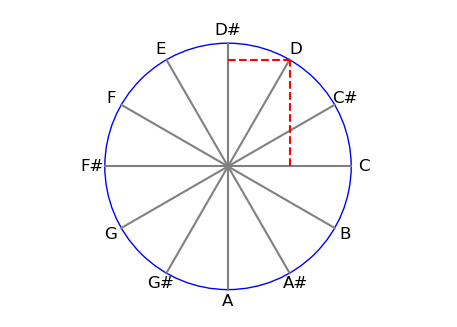

I think this opens up a lot of possibilities. When trying to create note representations that could make sense to my transformer, I was thinking about how musical pitch is circular in nature: When we move from a C up on a piano, we end up at another C, one octave higher. To create a representation for this, I decided to add two features for each note: I considered each note in the chromatic scale a point distributed around a unit circle, and added the sine and cosine values to the note features. Another idea was to add similar circle-of-fifths values to the notes, to increase the harmonic relationships between notes, but I didn’t get around to implementing that.

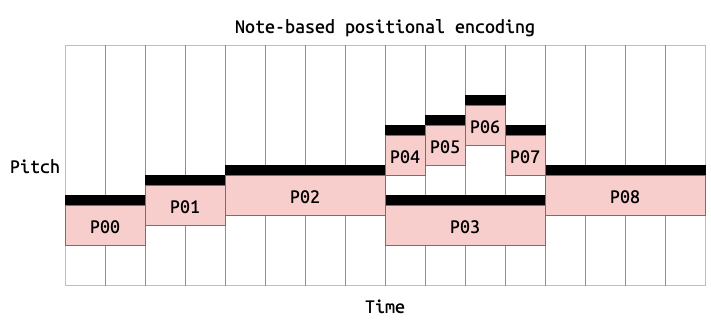

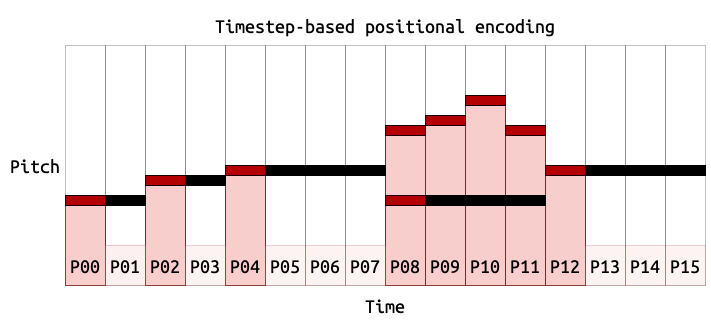

Timestep based position encoding

I also wanted to give the model timing information that was more rhythmically relevant. Positional encodings usually indicate each item’s position in the input sequence. In a chord all notes are played simultaneously, but they must be fed to the transformer in a sequence. I first added an “onset delta” to show the time difference between two subsequent notes and counters to indicate where in a bar a note would fall. Then I decided to try changing the positional encodings to represent one timestep of music (which corresponds to a 32nd note), rather than just a sequence index. So if several notes land on the same timestep, they will receive the same positional encoding, and the difference in encodings show the difference in time between notes. My intention was that this would give the model more meaningful timing information that would eventually create more rhythmically coherent output.

Examples

To conclude, I had a lot of fun working with the Chiptransformer. I learned a lot and I felt I could use my creativity when implementing things the way I wanted. Unfortunately the outputs I generated were far from as meaningful as I hoped, which was a bit frustrating. Still, I am motivated to continue working on this project to make it work better.