Connecting Eigenrhythms and Human movement

This blog post explores a machine learning pipeline designed to classify music genres based on MIDI drum patterns and how to relate it to human movement.

Two different CNN models is proposed that aim to discern rhythm data from the accelerometers in smartphones, bridging the gap between music analytics and human movement. Much like how we instinctively nod along to the groove of a song, this project seeks to delve deeper into this intuitive interaction.

The objective here is not just to identify well-known rhythmic patterns but also to provide insights into how these rhythms are physically executed. Exploring the “feel” of a genre’s groove to see if machine learning can enhance our understanding of, and interaction with, musical rhythms.

A lot of the work done is based on the idea of “eigenrhythms”, which by John Arroyo et. al, is defined as an high dimensional rhythm pattern, which has been reduced to a lower-dimensional representation [2].

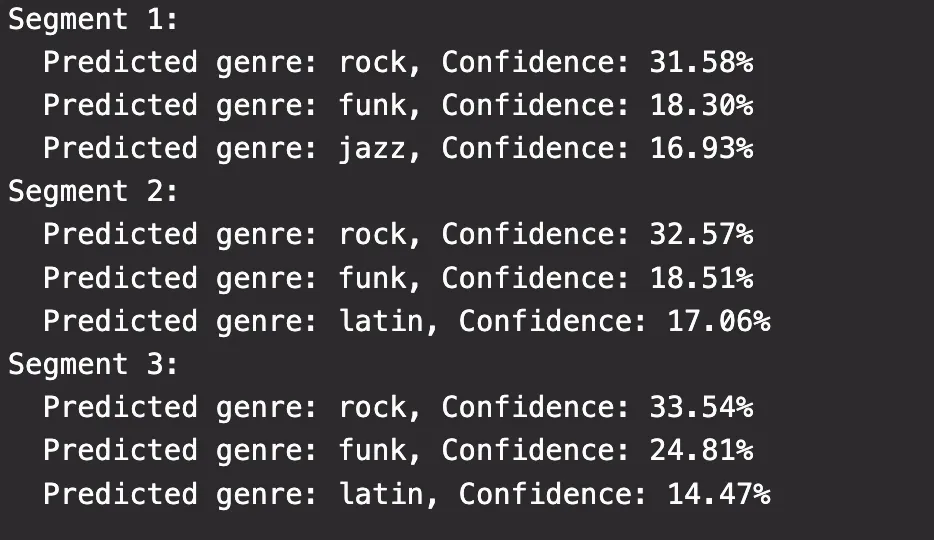

By using movement data, in this case provided by a phone’s accelerometers, we can then try to create a one dimensional rhythm and see what genre the model would classify it as. In the video we can see how the accelerometer data is generated, and in figure 1 we can see what genre one of the model classified my rhythm with.

Dataset

The dataset used is made by Magenta [1] and contains over 1,150 midi files, performed by 10 different drummers playing up to 17 different genres. The dataset is however skewed where there is definitely most rock, jazz and latin songs, which does effect the result somewhat.

Data processing

This pipeline uses signal processing and machine learning techniques, including Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and convolutional neural networks (CNNs).

The first step of preproccesing the data is sequencing the midi data to not overload the CNN with too much data at once. As the goal is for the model to recognize temporal patterns, I have segmented each midi file into 2 bars with 32 timesteps. We can see one such representation in the picture here, showing 22 drum instruments, over 32 timesteps.

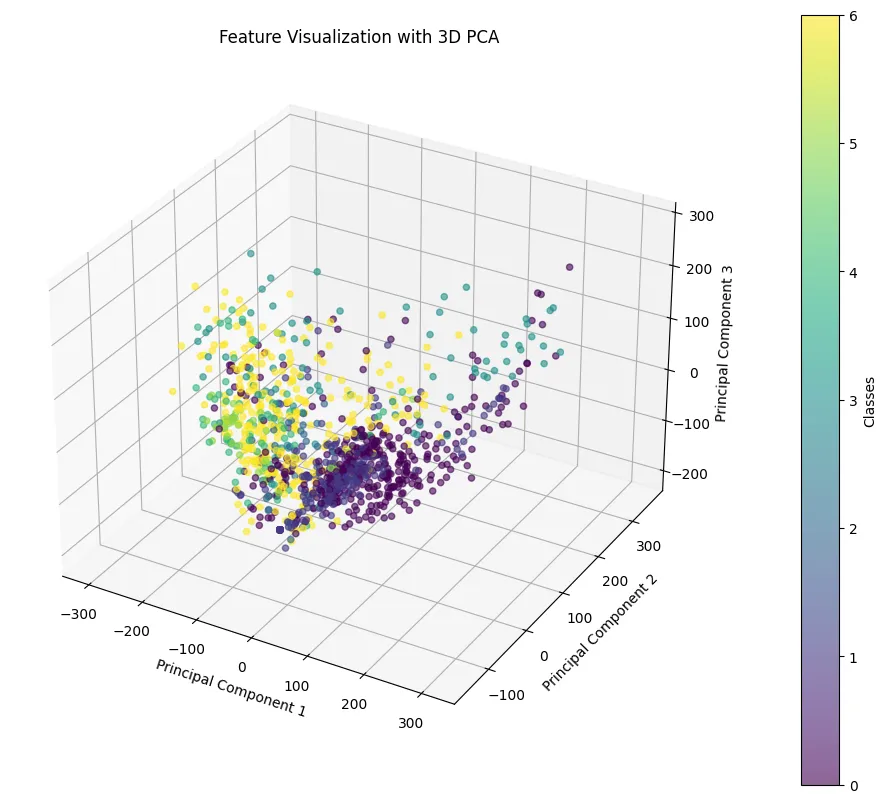

PCA allows for these methods allow the system to effectively reduce dimensionality and highlight critical features within the data. It works by identifying the axes (principal components) along which the variance of the data is maximized.

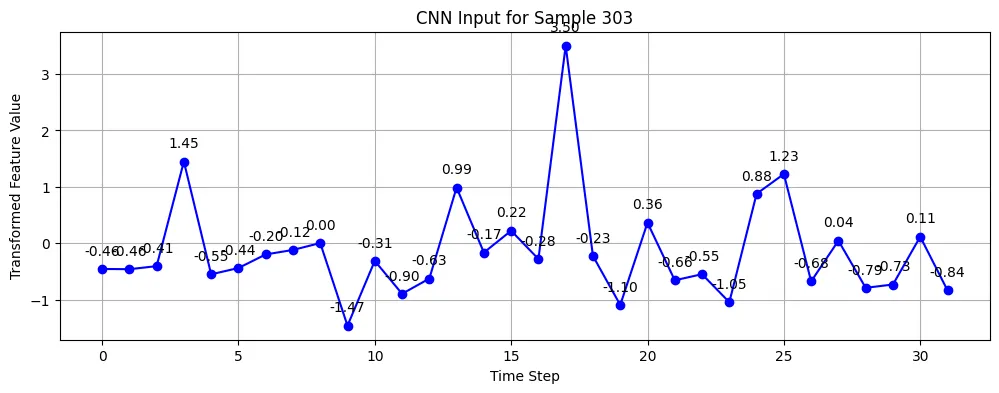

In figure 3 we can see the same drum roll in figure 2after it has been reduced to a one dimentional eigenrhythm using the first (best) principle component.

Another method introduced is Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA). It is employed in machine learning and statistics to improve class separability by finding a lower-dimensional space that enhances the distinction between class means while minimizing in-class variance. This layer could further help discriminate between genres.

CNN

First a baseline CNN model was made. It trained on several thousand segments with 22 instrument dimensions over 32 timesteps as in figure 2, to recognize the statistical patterns in the temporal dimension of the midi signal.

Two eigenrtyhm models were proposed to expand on the baseline CNN model. One model used a PCA layer on each timestep, finding statistical variations for each timesteps, reducing every step down to 1 dimension as seen in figure 3. The other used a global PCA layer to reduce down to 5 dimension, and then a LDA layer to further reduce down to 1 dimension.

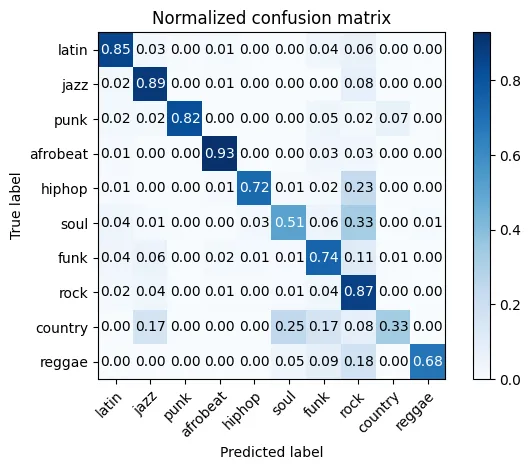

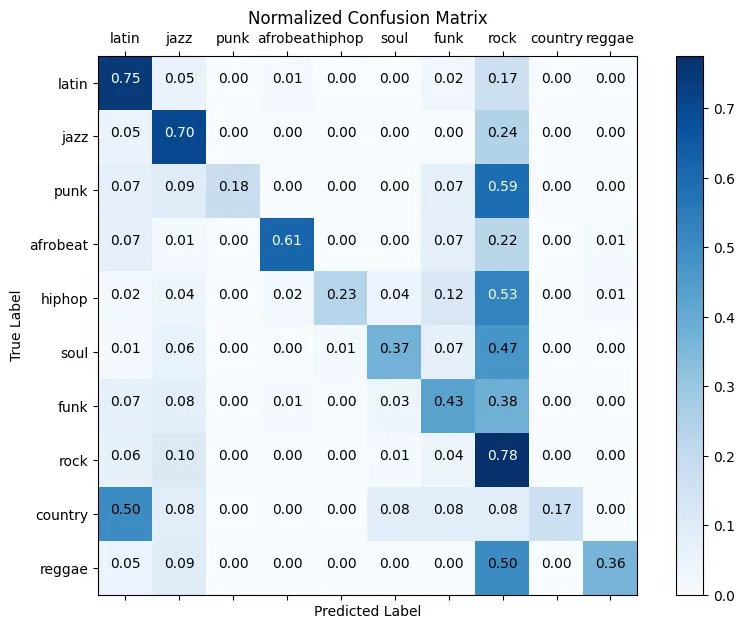

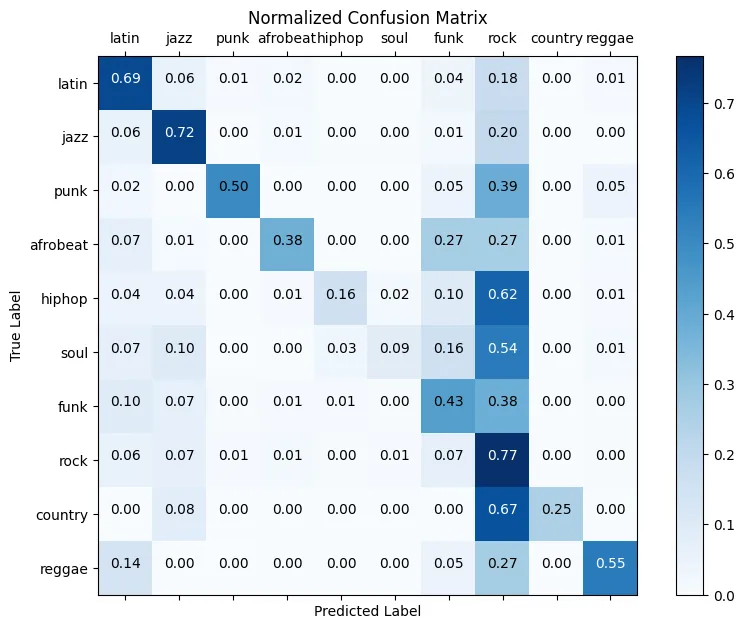

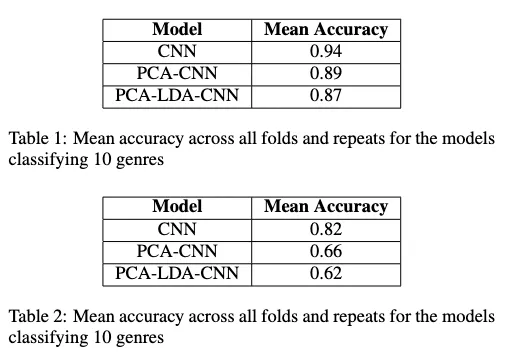

The eigenrhythm models definitely decreased the accuracy compared to the baseline CNN. Which is not strange as there are now 21 less dimensions the CNN can train on. The change is however only around 5–10% depending on how many genres the model is trained on.

If only the classification was in focus, the pure CNN model might still have the best results, but to explore the eigenrhythms and relate it to the movement data, it is imperative to reduce the dimensions down to 1 to be able to compare the data.

Using repeated k-fold analysis the different models, I got these results:

Connecting to movement data

For accelerator data, I have used an app called phyphox (but any similar app would work), which simply records accelerator data from my phone, and exports it as a CSV file (Type:Comma, decimal point). When loading the data, it puts it into an empty 22x32 matrix, and then uses the same PCA filter as the model is trained on to reduce it down to 1 dimension again, and then feed back into the PCA-CNN or PCA-LDA-CNN model to make an prediction. It does however matter what type of data the model is trained on.

After having trained the model on the chosen genres, I then wanted to see how this relate to how we humans would “feel” the rhythm of a genre. Since the model is trained on a large viarity of samples, it could be able to identify some of the same patterns. If the model is only trained on jazz & rock, the model would simply output if they think your rhythm is more alike rock, or more alike jazz. The model utilizes a softmax filter at the end which simply picks the genre based on the highest probability. So if it was very unsure, but thought it was 51% rock and 49% jazz, it would say that it think your rhythm is rock with 51% confidence.

Having more genres increases the possibilities, but having consistent larger than 1/n in predicted outcome, where n is number of genres, would imply the prediction is based on more than just pure probability.

Conclusion

The work here is a continuation on the idea of “eigenrhythm”, and to see if there is a connection to how we “feel” rhythm. There are a lot of variables that could be tweaked to improve all the aspects of the pipeline, and even more that could be added. Using a mocap suit would increase the number of movement dimensions available, increasing the number of dimensions the model can be trained on.

It can have practical applications of drum training tools. By tailoring the training datasets to specific needs — whether different musical genres or distinct styles within a band’s discography. This approach not only allows for genre-specific training but also enables exploration of diverse rhythmic “grooves,” potentially changing the way we understand and teach musical rhythm.

Sources

[1] https://magenta.tensorflow.org/datasets/groove

[2] https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8PG2230Links