Recognizing Key Signatures with Machine Learning

Introduction

My machine learning project this semester is all about generating chords to a melody. For a model to learn how to generate chords, we need lots of chords to show it – and I mean a lot of them.

My model is trained on around 3 million chords, all of which are extracted from MIDI files. I use a subset of the Lakh MIDI dataset, which consists of around 17,000 MIDI files of popular, classical, and jazz music. Like many large datasets you can find online, the Lakh dataset is not a ‘clean’ dataset. It essentially consists of MIDI files pulled from across the internet, which means it has all the errors, corrupt files, and formatting inconsistencies that we might expect. One of the most challenging inconsistencies I had to overcome in the dataset was that only around 20% of the files contain key signature information.

The solution to this issue required a second machine learning model, a good understanding of the data, and a solid grasp of basic music theory. As such, this post will assume you have a basic understanding of classification machine learning models and music theory.

Music Theory Meets Machine Theory

Why do we need key signatures for determining chords using machine learning? The reason has a lot to do with the music theory concept of functional harmony.

The goal with my final chord generation model is to generate tonal and coherent progressions to accompany a melody. Chord order, and the relationship between subsequent chords, is essential for the generated progressions to be musically coherent. We can consider it in terms of functional harmony i.e., does the progression go where we expect it to go? V chords often lead to I chords, for example, and it is important for my model to learn these types of relationships.

In order to represent my dataset to the model in terms of functional harmony, I first decided to transpose every MIDI file in the dataset to C major/A minor. To transpose a song by the right amount, we first need to know its original key. This is where machine learning comes in.

I therefore used the files from my dataset which do contain key signatures to help me recognize they keys of those that do not. For each file, I needed two pieces of information: a) the key signature of the song, and b) a chroma histogram of the song. A chroma histogram is simply a list of 12 numbers which describes the percentage of each type of note in a given set of notes. In this list, the first number refers to the percentage of C’s, the second the percentage of C#’s, etc. The percentage of each type of note is closely related to the key signature. For example, we’d expect to see a lot of C’s but few F#’s in a song in C major. This trend in the data mean that I can train a classification machine learning model on this data, feeding it the histograms as the input, and asking it to predict the key signature as the output.

Key Confusion

As with all machine learning tasks, it rarely works well the first time out. I plugged the data into a Support Vector Machine model in SciKitLearn, and it predicted keys with an accuracy of… 68%. Not bad, but we can do better.

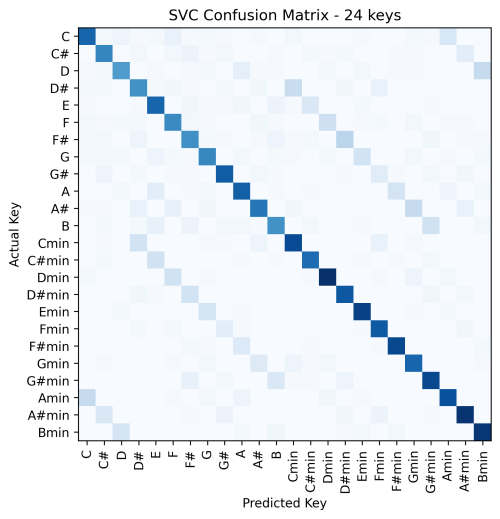

We can understand the mistakes our model is making by plotting a confusion matrix like the one below.

The X axis shows the key as predicted by our model, while the Y axis shows the actual key. The dark diagonal line shows that our model is getting it right most of the time. However, we can also see some fainter lines illustrating common errors. For example, C minor is often being confused with D#/Eb major. Why is this?

Let’s turn back to music theory. Eb major and C minor are said to be ‘relative’ keys to each other as they contain the same set of notes, they just start the scale from a different place in that set. Our model is therefore being confused by this major/minor distinction as it has two possible labels for chroma histograms that look very similar.

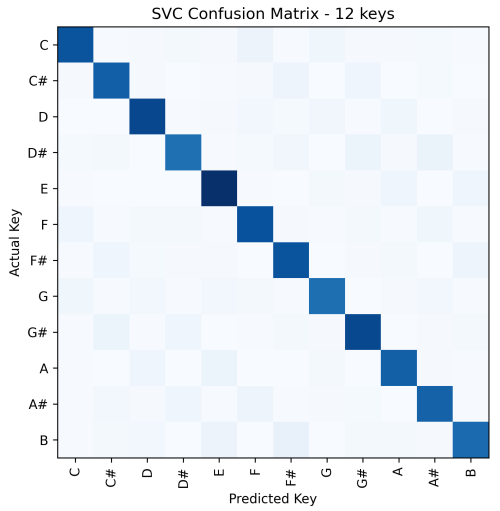

I therefore decided to remove this distinction by converting all minor keys to their relative major. This meant I now had only 12 keys, rather than the original 24. I re-trained the model with this newly adapted data and the accuracy jumped immediately to 84%. Much better! See the confusion matrix of this new version below.

Conclusion

With my key classification model accuracy up to 84%, I was then able to deploy it for recognizing the key signatures of those MIDI files which didn’t contain one already. Despite taking place entirely behind the scenes, this is a vital component of my project which allows me to present the chords in my main dataset to the final model in a way that captures how they relate to and interact with the chords around them, rather than simply by the raw chroma pitches involved.

When I first started working with machine learning this semester, a common refrain was ‘know your data’. It can be easy to think that work with MIDI or other symbolic representations of music should be easy. It’s just a list of instructions after all - how hard can they be to interpret? As my challenges in building an effective key signature classifier show, working with MIDI throws up its own set of challenges that require you to really ‘know your data’.