MIDI music generation, the hassle of representing MIDI

Introduction

As there has been advances in generative AI, there has also been a lot of research in generative music using Neural Networks. But if you want to generate music, you need to represent music. The two main methods are using symbolic music representation or audio representation. In audio representation, you represent sound as frequencies. This can be challenging due to the fact that audio is sampled using frequencies at several thousand hertz. This requires a huge amount of computational power to be able to train on a big amount of data. The other option is to represent music symbolically. Here, a large amount of music can be represented with a lot less data. Simple, right? No..

MIDI: The bohemyth

MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) was made in the early 1980s as a way to connect electronic musical instruments and computers. The ease of use made it so that it became the leading way of symbolic music representation. So why isn’t this then fed to the Neural Network? Well, one of the problems is that MIDI both has a lot of redundant information, it is noisy and complex. Neural Networks also experience a lot of trouble with keeping track of sequences with the way MIDI uses note-on events, and a corresponding note-off event to keep track of playing notes. It becomes a 1D representation to represent 2D information. This is shown to be challenging for Neural Networks. So instead of representing symbolic music as raw MIDI, we need to preprocess it, doing some feature extraction.

Let’s clean up MIDI

Since MIDI is too noisy and complex, a solution can be to strip it down a bit. A lot of redundant information about the track can be removed, and the information can be stripped down to just the note events that MIDI represents. TensorFlow teaches this in their generative MIDI guide (source). They also remove the note-on and note-off events and instead use step and duration to represent the time between notes, and duration of a note being played. This is due to the fact that every note-on event needs to be closed by a note-off event. This can cause trouble since a note-on event without a corresponding note-off event will cause an error. This method works, and works better than raw MIDI data, but it is still considered a 1D representation, where the values of step and duration dictate the timing information. So it suffers from the same challenges that raw MIDI data does.

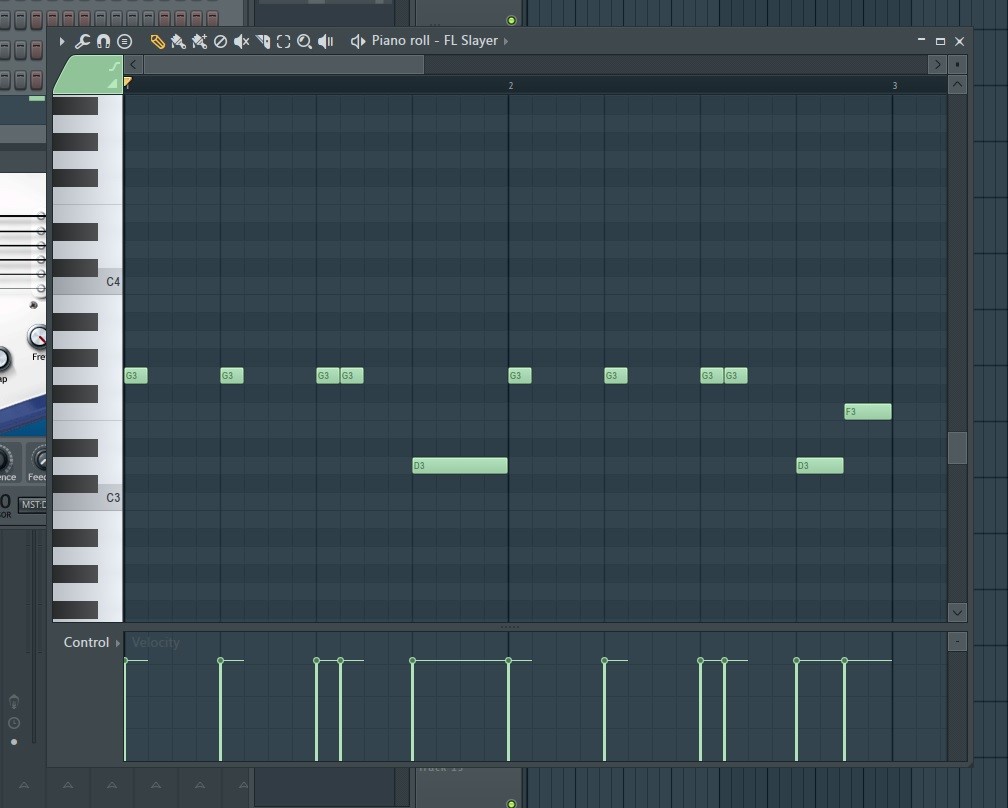

Adding time dimension with piano roll

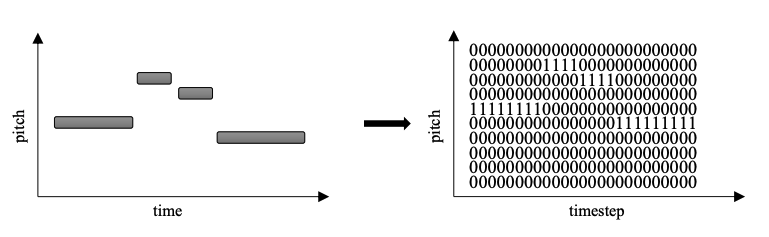

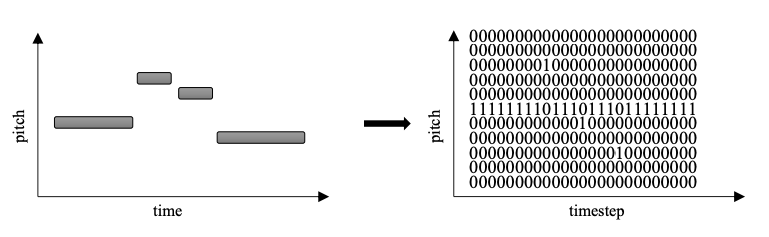

To solve the problem of having 1D representation, we need to convert the 1D midi data to 2D data. The most common method to do this is piano roll. In piano roll, instead of representing each note by a group of values, it quantifies time into time steps and represents each time step as a vector. Each of these vectors will normally have up to 128 numbers, where each represents one pitch. These numbers are often ‘1’ for active notes and ‘0’ for inactive notes. This quantification is done in fixed intervals in contrast to 1D representations which only samples on notes. When doing this over several time steps, we get a matrix where each column represents the time axis, and each row represents the pitch played at each time step. Now we have a 2D representation. It now has a more structured sequence representation, due to the constant time interval between two successive columns.

Piano roll, the perfect choice?

So this is it, we now have the perfect way to represent MIDI? Of course not.. There are several problems with piano roll as well. Some have workarounds like the fact that there is no way to represent silence, or that there is no difference between a sustained note and two rapidly played notes. Silence can be represented by adding a row that is active when no note is played, and sustained notes can be represented by another symbol like ‘_’ in the matrix instead of ‘1’.

But some problems are not solvable with quick fixes, like the fact that piano roll has very high memory consumption. This leads to a need for powerful equipment needed to train models using large amounts of data. In my research I use a low sampling rate when sampling the piano roll. But still for every number 1D representation uses, standard piano roll uses over 330 numbers.

What other 2D representations are there?

Relative pitch

Since piano roll is imperfect, a lot of clever ways to reduce memory consumption have been introduced. One of them is often called relative pitch. With relative pitch the goal is to reduce the size of the piano roll. It relies on transition data. You can simply make a piano roll that only looks at the transition in pitch between the current note and the previous. If no transition is made, the middle row is active. If the transition is 4 half steps, the row at index (middle row + 4) is active. If the transition is down 3 half steps, the row at index (middle row - 3) is active.

No transition is normally not bigger than one octave up or down, and if it is it is kept in range with a modulus 12 operation. Therefore it only needs 12 + 12 + 1 = 25 values to represent an octave up, an octave down and remaining at the same pitch. This is less than 20% of what a full piano roll uses.

Character based

The reason why both piano roll and relative pitch uses a vector of numbers either ‘0’ or ‘1’ is because Neural Networks learn using numbers. For instance learning using ‘0’ to show inactive ones and ‘1’ to show activeness in a vector of length 128 (called one hot encoding) has been found to be a lot easier for a Neural Network than learning to predict a number between 1 and 128. But there are some networks called character-based networks that can learn characters. Using them, you can represent advanced musical structures, using characters. This is an entirely different field, deserving a blog post in itself, but it has also become popular. Instead of needing a vector for each timestep, you can use letters.

Conclusion

To conclude, sequence music representation sounds simple, but it is not. When we want to represent complex data like sound, using as little memory as possible, we often lose something. The key is to find a compromise between being what we get and what we lose.