Generating Samples Through Dancing

Introduction

When we dance to music we are reacting to the sounds that we hear, interpreting elements of the music that stand out to us with our bodies. For example, if the music is louder we might make larger movements or we might time our movements to be on the beat. Therefore if we look at a video of somebody dancing we have a record of several elements that were in the music that they were dancing to. Can this record be used to reverse the process, and generate new music that possesses characteristics that were found in the music was originally danced to?

This was the question underlying the Sampling Through Dance project. Using a dataset of videos and audio files of the accompanying music and a machine learning architecture called the Varational AutoEncoder (VAE) [1] a generative model was trained. This was then attached to a live camera input, creating a sampler style instrument, and through dancing the generative sampler is played.

System Design

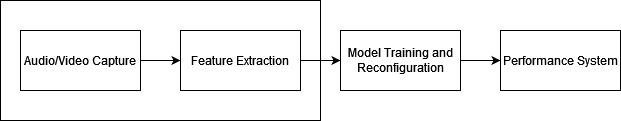

The system comprises three main components:

1. A component to capture the audio and video input from the computer soundcard and a camera and create a dataset to train the model with. These data are chopped into sample segments of the length desired.

2. A VAE component that is trained on the data captured. A VAE is an artificial neural network architecture which is trained on an identical input and output. The data is compressed into a bottleneck, the ‘latent space’, and then reconstructed at the output. However, what’s interesting about VAEs is that this latent space is actually a representation of the parameters of a distribution of the data, and this is what provides the architecture with its generative capacities.

Here, the data of the dance motion and the corresponding audio segments are encoded together in a shared latent space. After the model has been trained, the input for the audio and the outputs for the motion data are removed, meaning that motion data can be passed to the model to sample the latent space and generate new audio samples.

3. A performance system, centred on this trained model. A live camera input is attached to the model and through dancing, music is generated.

Representing Motion

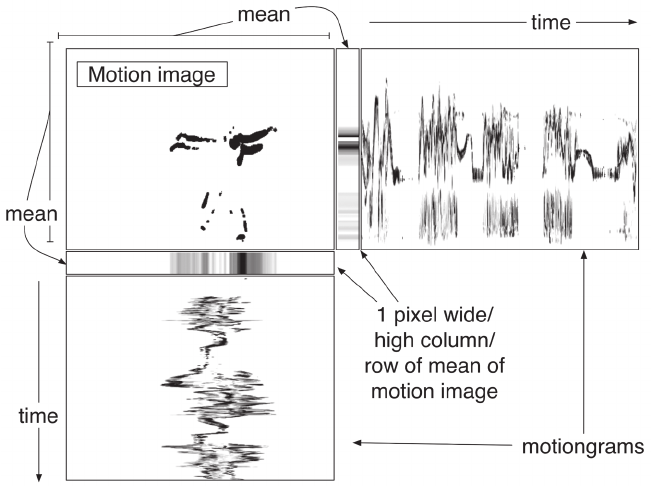

Passing raw video files to the model for training and in the performance system was not a good idea for a number of reasons. Firstly, raw video files are extremely large and would greatly increase the time required to train the model and the time required to generate new material. Secondly, when using the model after training, the environment and camera setup would have to be identical to that in which the data to train the model was collected. Instead, motiongrams [2] were extracted from each sample segment and used to represent the dance motion.

A motiongram is a representation of motion along an axis through time and is created by calculating the mean of each column or row (depending upon whether an x-axis or y-axis motiongram is desired) of the difference between each frame in the video data. In this way, each row or column represents a single frame of the original video, greatly reducing the size of the data. In addition, they offer a good representation of both the quantity and location of motion, capture the temporal dependencies of the motion, and are also environment ‘agnostic’, due to the fact that they are calculated from the frame difference. This means that the system can be used to perform in environments different to those in which the data was collected.

The Prototype

A prototype of the system was developed using a dataset of around one hour of dancing to the album Reward by Cate Le Bon.

Two models were trained, one with a sample segment length of 0.1 seconds and 0.5 seconds. The following videos demonstrate a short performance with each, showing the video as captured by the camera (at a low resolution of 64x48) along with the motiongrams that were passed to the model.

The results are rather interesting and not what were expected at the outset of the project. Instead of distinct audio samples, there instead is a shifting textural quality to the sound over a droning bass that occasionally changes pitch. There is also a repeated phrase underlying all of the segments. The VAE also adds a lot of noise, but this isn’t spread evenly throughout the frequency spectrum. Instead, this is mostly found in the higher frequency bands.

Looking at several characteristics of the sound and motion, it’s possible to see that the element best captured by the models was the link between the quantity of motion and the dynamics of the audio segment, with larger motion resulting in a louder segment. The rhythm is set by the length of the sample segment, meaning that there this element cannot be captured by the model. These three aspects create an interesting collaborative effect when dancing with the system. The timbral and harmonic elements of the texture feel very out of the control of the dancer, while the dynamics feel very manipulable, with the rhythm being set in advance. This creates an effect that one is dancing with the system, and not fully in control of it.

The Issue of Latency

There is an issue when it comes to using motion data as an input for machine learning model in a performance system. There are several figures provided on the maximum latency between motion and sound in a motion controlled system in order to create a sense that motion is creating the resulting sound, ranging from 0.02 to 0.15 seconds (see, e.g. [4], [5]). However, as a machine learning based model requires the motion to be finished before the resulting sound can be generated, the length of the motion itself is already creating latency (for the two models here 0.1 seconds and 0.5 seconds respectively). This is in addition to the time taken by the model to generate the audio, which (on my computer) was around 0.1 seconds for the 0.1 second model and 0.2 seconds for the 0.5 second model. This results in a total latency of around 0.2 seconds for the 0.1 second model and 0.7 seconds for the 0.5 second model, both of which exceed the maximum to create a sense of link between motion and sound.

Although this latency was noticeable for the 0.1 second model, there was still a sense that the motion is creating the alterations in sound. However, for the 0.5 second model the latency was so large that there is a feeling that the system is reacting to the motion, not that the dancer is creating it through their motion. This adds to the feeling that the dancer is dancing with the system instead of controlling it. For the above videos demonstrating the system, the audio was aligned with the motion to remove this latency, in order to show the direct link between the motion and the musical elements.

The code for a pipeline system to capture the video and audio for a dataset, train a model and perform with it can be downloaded here.

Sources

[1] D. P. Kingma and M. Welling, ‘Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes’, 2013, doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.1312.6114.

[2] A. R. Jensenius, ‘Action-sound: Developing me-thods and tools to study music-related body movement’, Ph.D Thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo, 2007. [Online]. Available: https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/27149/jensenius-phd.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[3] A. R. Jensenius, ‘Some Video Abstraction Techniques for Displaying Body Movement in Analysis and Performance’, Leonardo, vol. 46, Feb. 2013, doi: 10.2307/23468117.

[4] T. Mäki-patola and P. Hämäläinen, ‘Latency Tolerance for Gesture Controlled Continuous Sound Instrument Without Tactile Feedback’, in Proc. International Computer Music Conference (ICMC, 2004, pp. 1–5.

[5] R. Gehlhaar, ‘Sound= Space: an interactive musical environment’, Contemporary Music Review, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 59–72, 1991.