Clustering high dimensional data

Filmstill ‘The Truemanshow’, retrieved 13.09.19, 06:26

In this project I was using raw audio data to see how well the K-Mean clustering technique would work in structuring and classifying an unlabelled data-set of voice recordings. This blog post is a reduced approach towards the course project.

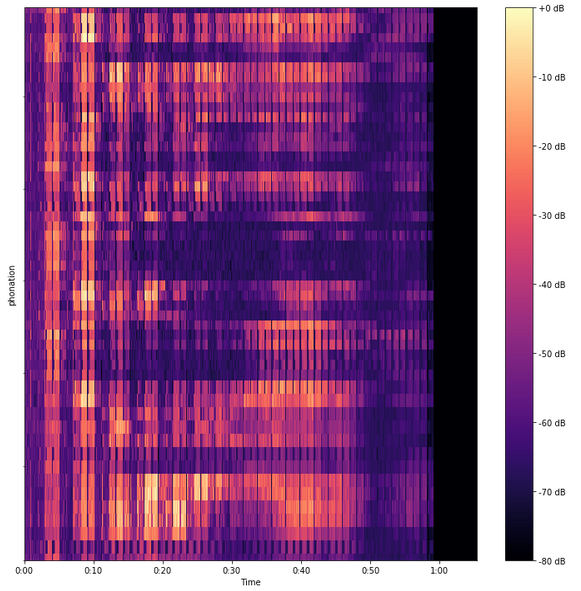

The data-set “Phonation modes dataset” designed by Polina Proutskova (2012) is a collection of vocalised phonation modes for training computational models in automated detection of these phonation modes. 4 different states were sung by one female singer, breathy, neutral, flow and pressed. Out of 900 samples, pitch C4 was preprocessed into 53 unlabelled samples. Each sample is one second long and contains one vowel vocalized in each of those phonation modes. In order to enhance the audio signal (Schuller, 2013) and prepare it for feature extraction some preprocessing is required. The found set-up therefore made slicing of the original files into smaller units via the xxx function not necessary. To optimize the test/training performance of the clustering algorithms, dimensional reduction of the samples could be directly applied as length and frequent sound occurrence enabled further processing of the raw signal.

Phonation modes differ in their loudness (Sunberg), while a breathy vocalisation is soft for example, pressed sound would be louder. Further on Polina Proutskova explains in Sundberg’s model loudness would directly be related to subglottal pressure, and subglottal pressure would rise from breathy to neutral to pressed. (Proutskova)

Data mining in music

It was not only helpfull for the understanding that the procedures presented in this project are to be situated within the field of data mining. It helped to critically assess and reflect upon the tools deployed. According to Tao and Lei Li, data mining is the nontrivial extraction of implicit, previously unknown, and potentially useful information from large collection of data. The mining process would usually consists of an iterative sequences of data management, data preprocessing, mining and post-processing (Tao Li and Lei Li, 2019).

Data & Feature Computation

In the data mining process the computation of features is the first step. From all the different features (high dimensional data) a subset of features have to be selected and dimensional reduction applied, otherwise the clustering algorithm will have a hard time allocating the nearest neighbour of the data points. In this project only one feature was tested.

Dimensionality Reduction with Isomap

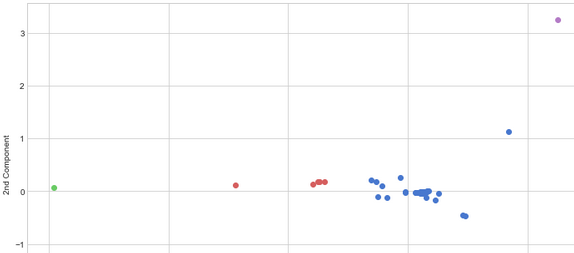

The high dimensional data, already trimmed and sliced beforehand will be now represented in a lower dimension, organized by similarity. With Isomap – isometric feature mapping - it is possible to apply a non-linear reduction method (see benalexkeen). The key is to find relationships among data points, measuring the geometric shapes formed by items in a non-linear data set. They become predictable in high dimensional data (see trnmag). For pattern recognition on real-world data the algorithm is useful to see what kind of data there is.

Clustering with K-Means, unsupervised learning

As a method of classification the data can be segmented through shared attributes. This algorithm only uses input to group and structure the data without knowing the outcomes (i.e., unlabeled data without defined categories). The data points are grouped into clusters according to their similarities. Each cluster is defined by a centroid in which the data points relate in the squared eucledian distance (compare datascience). After running test/training the data in K-Means there are three centroids detectable around which the data is clustering:

There are 4 clusters, the largest group are obviously the blue dots which in respect to the used feature, must sound quite similar. There is a smaller group of red dots and one purple and green dot each. It could be possible, that the difference of the phonation modes are not so well expressed through the computed feature. More features or one different one could be applied to achieve more differentiated results. However, the results are hard to interpret since there only 53 processed samples. After applying unsupervised learning on the data set, I also noticed the remark of the researcher who created the set, in which she is not recommending using the recordings of the flow mode for recognition purposes.

Final thoughts, further application

Consulting all data that is available might have produced interesting results. It could probe a test-run to explore weather or not the entire data-set could be suitable to train an algorithm for a real-time sonic interaction, in the context of vocal trainings for example for humans. But to achieve meaningful results with these techniques (like Recurrent Neural Networks) much more data must be deployed and storage is needed. The 900 samples available were except for pitch C4 unprocessed. For the scope of this project it would have been too time consuming to trim the original files into a format the algorithm could digest. The samples were recorded in an supervised, controlled environment using only one voice.

References

-

https://osf.io/pa3ha/ - Data-set on phonation modes

-

The Machine Learning Algorithm as Creative Musical Tool – Rebecca Fiebrink and Baptiste Caramiaux

-

Online, Loudness-invariant Vocal Detection in Mixed Music Signals – Bernhard Lehner, Jan Schlueter, and Gerhard Widmer

-

Mechanisms of Artistic Creativity in Deep Learning Neural Networks – Lonce Wyse

-

Music Data Mining: An Introduction – Tao Li and Lei Li

-

Chain of Audio Processing and Audio Data in Intelligent Audio Analysis – Björn W. Schuller

-

https://www.datascience.com/blog/k-means-clustering

-

http://benalexkeen.com/isomap-for-dimensionality-reduction-in-python/

-

http://www.trnmag.com/Stories/031401/Tools_cut_data_down_to_size_031401.html