The Puzzler: A Tectonic Interactive Music System

Introduction

Introducing the Puzzler, a interactive music system that is designed with architecture in mind. Specifically the puzzler is designed to be a representation of how ideas from architectural tectonics can be realized in interactive music systems.

The Model

The reason this idea in Architecture came to inspire this project was partly due to a visit my sister made in the summer. My sister is very interested in going into the field of Architecture and Design so she took a online class last summer. Because of this, I was able to listen in an learn a bit about architecture myself. I helped her out with a couple of projects but because of the delicate nature of the models she entrusted me with one of the models she made. As I was thinking about what kind of structure I would make for the Interactive Music Systems class, I imagined how this model could be used to house sensors to make an interactive system.

WHat the Heck is Tectonics??

Architectural Tectonics is described as the art of construction, it focuses on taking the construction of an object and elevating it to an artistic form. This idea is similar to the concept of ‘process over plans’ in interactive design, basically trusting that the process of creation itself bring out the creativity in a system. In his thesis, Robert Maulden specifies that the process is about bringing the physical material from physical to metaphysical, gathering both external and internal references.

Design and Implementation

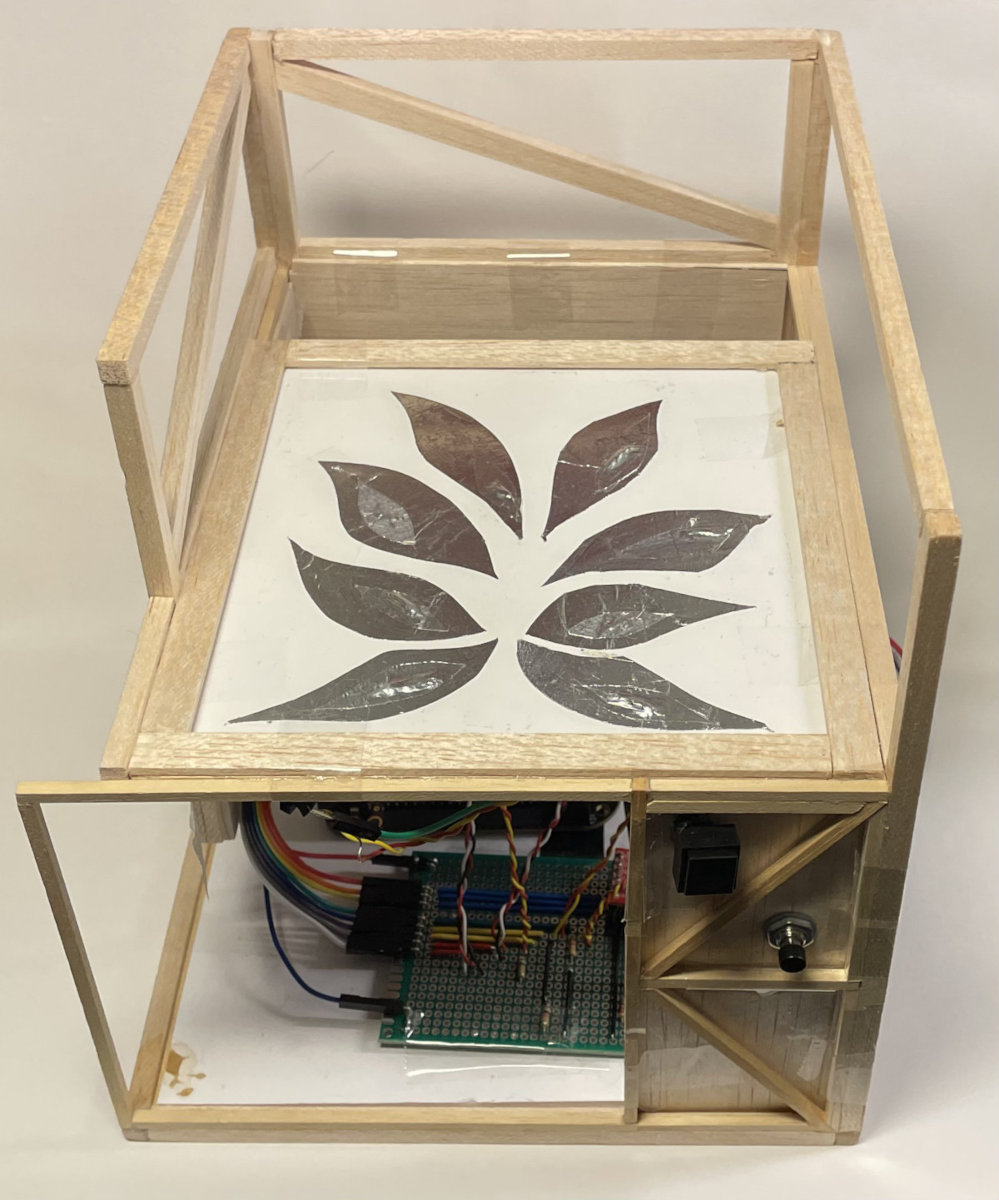

Because of these references, I started with an exercise I had seen previously in a project my sister completed for her architecture class. It involved creating several square frames from balsa wood, each with differing sizes, and creating a design that fit within an imaginary cube based on the dimensions of the biggest frame. In defining these borders, we are confined to a limited space in which we design our interactive interfaces. I wanted each side to look different when faced head-on and have a specific interaction or feedback type.

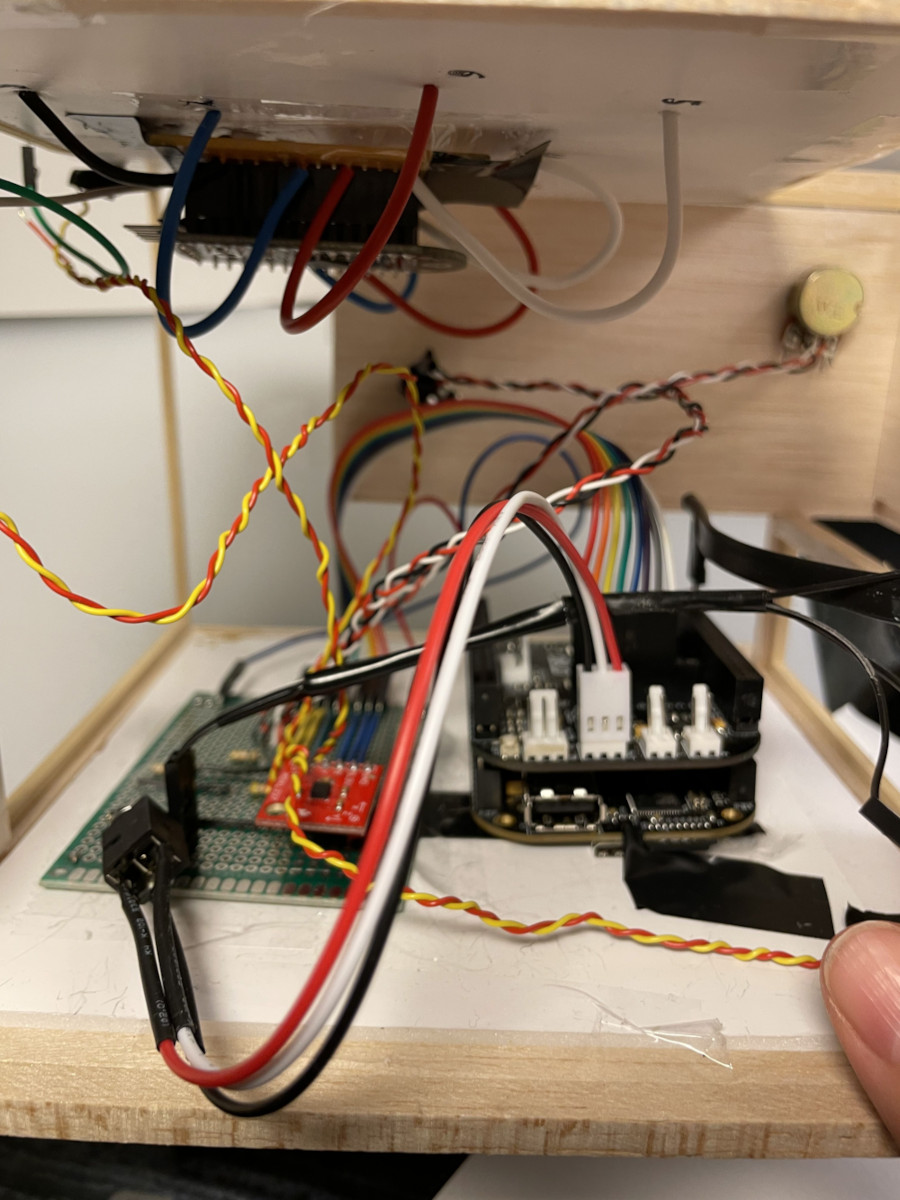

I assembled the frames within the structure with glue and strengthened the design with supporting pieces of wood. As I went along with this process, I noticed how the various support beams inspired different spaces in which sensors or actuators could fit and how many they would support. As I continued with this plan, I completed the initial structure on which my panels would be placed. When designing the panels, I initially placed foam boards with tape to test different layouts. I enjoyed seeing the electronics within the structure as I went along, so I kept a lot of space between the panels open so the user could see them. The Puzzler is supposed to be a fun play on traditional MIDI controller input devices. The most popular of these models contains multiple kinds of controllers, including musical keys, push buttons, knobs, and sliders. For this project, I took the first three of these types of controls and experimented with creative ways to introduce this to a 6-sided irregular structure.

Since the structure roughly resembles a cube, I chose six kinds of interactions, each representing the six different sides. These six interactions include:

Accelerometer - equipped with machine learning, it changes the wave type depending on the side facing up on the puzzler

Single Color Light Emitting Diodes (LED) - Gives Visual Feedback for Interaction. There is also a secret riddle that needs to be solved in order for the system to start playing based off of LED feedback, hence the name the puzzler.

Momentary Buttons - changes the scale used in the sequence as well as the tempo

Light Dependent Resistor - Manipulates the filtering of the sound

Trill Craft Surface - Changes the notes played in the sequence

Potentiometers - Control Attack and decay of the notes.

User study

Both participants exhibited positive impressions of the system. One immediately remarked that it looked like the Bop It toy, which was a popular toy from the late 2000s. Both of them, though, once they started experimenting with it, had difficulty turning it on by solving the ‘riddle’ that needed to be held for 5 seconds. Because of this, I intervened for this part so that they could explore the other parts of the controls without spending too much time frustrated by the ‘riddle.’ When talking about how it differed from their previous experiences with musical instruments, one described it as way more “techy” and felt different from the ways they are used to playing their instrument.

The other participant described it as similar in some ways in that it reacted sonically to what the player was doing but “definitely different from a guitar.” When talking about their favorite interaction, both participants found the accelerometer wave type changing to be very engaging and played with going back and forth between the different sides. One participant also commented that the potentiometers “were also fun to play with.” For the last question, one participant was really interested in seeing the top surface working as it looked fun to play with. The other participant said that they would like to see it “play on its own” as opposed to needing to be plugged into the speaker so that it would be easier to play with.

Conclusions

The inspiration for the Puzzler is what gives it its unique character. The exploration of interaction and sound through the Puzzler highlights the potential of blending architectural principles with interactive music design. Through the use of a non-traditional layout, which is uncommon in MIDI controller interfaces, we can provide users with new ways of musical expression. The combined use of Pure Data, Bela, and various sensors allowed for an engaging experience ripe with inspirations for iteration. The process of creating the Puzzler highlights the importance of iteration, mapping diversity, and the balance of complexity vs. usability. The Puzzler is a model for the creative potential of interdisciplinary thought in the conversation about creativity and interaction.

References

P. R. Cook, “Re-Designing Principles for Computer Music Controllers: a Case Study of SqueezeVox Maggie,” in New Interfaces for Musical Expression, 2009. [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:5050967

J. Drummond, “Understanding Interactive Systems,” Organised Sound, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 124–133, 2009, doi: 10.1017/S1355771809000235.

S. Holland et al., “Understanding Music Interaction, and Why It Matters,” in Springer Series on Cultural Computing. , Switzerland: Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG, 2019, pp. 1–20. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-92069-6_1.

R. Maulden, “Tectonics in architecture : from the physical to the meta-physical,” Thesis (M. Arch.), Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Department of Architecture., 1986. Accessed: Dec. 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/78804