The SlapBox: A DMI designed to last

Introduction

While many Digital Musical Instruments (DMIs) today have been designed to showcase new ideas in research and academic spaces and offer us different perspectives on how to interact with sound, most of these DMIs lack the longevity of traditional instruments. This difference hinders many benefits of robust design in that it does not encourage long-lasting commitment to establishing the use of techniques and repertoire. The disconnect here, unfortunately, causes many of these instruments to be put on the shelf while the designers pursue new ideas or dismantle vital parts to be used in other projects. With conferences like NIME placing a lot of thought in recent years to sustainability in practices of DMI creation, The Slapbox offers us an example of what robust design built with prolonged performance in mind can produce.

The Concept

The Slapbox is actually the second iteration of a DMI for percussionists, with the original iteration being named The Tapbox (1). The team behind the new iteration specifically chose to work on the Slapbox design based on The Tapbox to highlight how solving old problems on older designs can improve the product while also introducing future design.

The Original Design

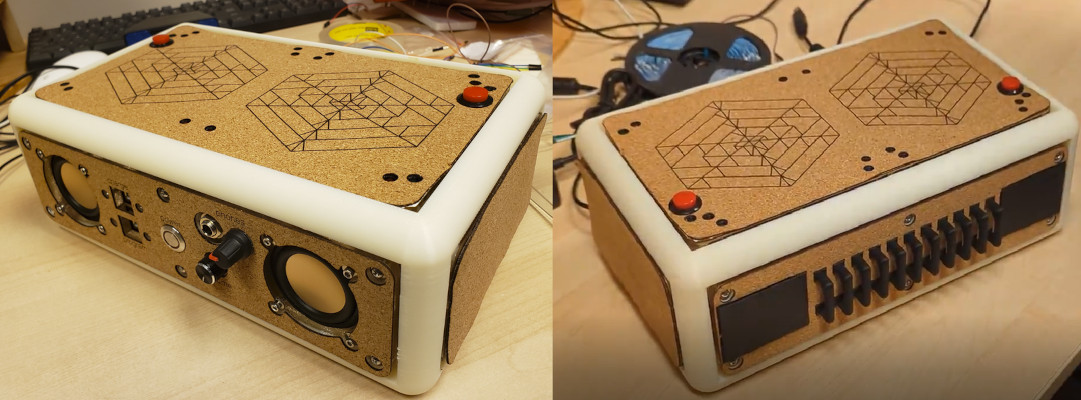

The design of this instrument takes its inspiration from commercial digital percussion controllers, which usually have some form of velocity-sensitive pads. When looking at the available examples of drum controllers, they noticed a lack of modulation gestures, which influenced the new elements they wanted in their design. The original Tapbox design was based on the Cajon instrument, and its multiple surfaces showcased how dynamic an instrument with multiple playable surfaces could be in performance. The main problems they saw in this original were the lack of sensitivity of some sensors as well as a lack of differing interaction types within the outside of the box.

Improvements with New Iteration

The new iteration still retains many of the older parts, including front panel speakers, auxiliary controls, and most of the internal electronics. The sensor pads on the Slap Box iteration require a unique solution capable of capturing extremely quick body movements. To find a solution that is commercially available and captured Velocity, Continuous Pressure, and Position, the team behind Slapbox decided to use a Force Sensitive Resistor with Velostat.

The Velostat was paired with a configuration of conductive tape that allowed the pressure source to be estimated and mapped to synthesis parameters of sampled percussion sounds.

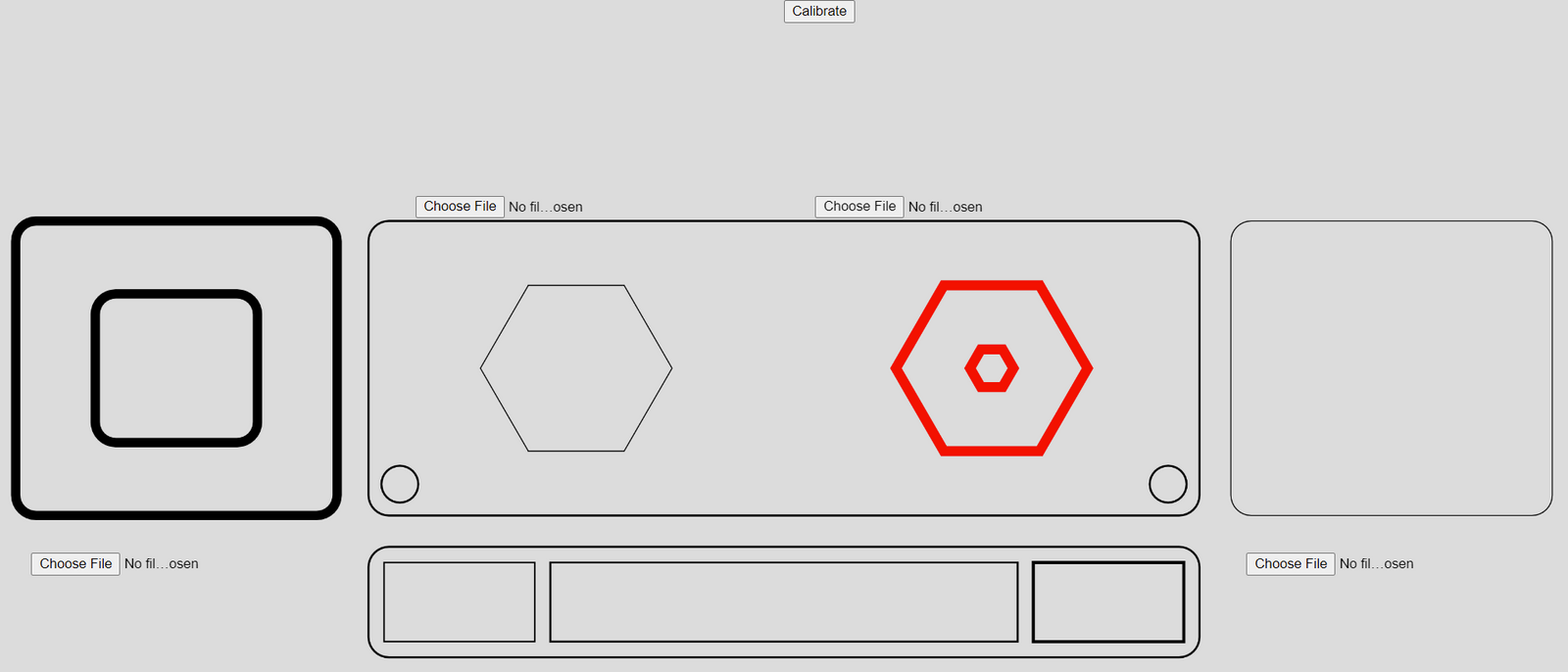

The new design also comes with a GUI that can be used as a visual representation of real-time strikes alongside visual feedback from the LEDs on the device itself

Testing

Performers were very quick to achieve interesting interactions almost immediately after picking it up for the first time. While initial trials exposed some false triggering this was quickly fixed with a new back panel. Those who used it appreciated its many unique features such as the gui, and modulation features.

What makes it stand out?

The Slapbox being designed around the Cajon makes for an instrument that many musicians, percussionists or not, have some idea of how to approach. Even so, the Slapbox is intrinsically its own thing, allowing the user to play this in a way unlike the average percussion set. It will enable the user to play in the way they want and develop the technique that suits their practice or setup. The sensitivity of the position estimation allows for the real-time synthesis to bring individuality to each strike. This can encourage users to develop a virtuosity with the Slapbox that might have yet to come about with synthesis less adept.

Along with all the features, the Slapbox is very obviously made to last. Unlike other DMIs, the Slapbox’s design feels permanent. Although the ideas surrounding the synthesis and sound samples still loom, the structure appears to be made to withstand much experimentation. The GUI allows for another dimension of knowledge of the instrument that can encourage those weary of trying a sort of instrument to be drawn to seeing exactly what their actions translate to in the synthesized world.

Why it matters?

DMIs should be made to weather a lengthy musical career. The disconnect between the commercial market and academic spaces in terms of durability makes musicians weary of trying experimental products in research spaces. Nine times out of ten, if a musician thinks of adding new interactions into their daily practice, they will go with a product that can withstand a fall or two and still work. To observe research instruments in performance spaces, we need to make something that musicians are not afraid to use. Moreover, we need instruments that are able to establish confidence in the relationship between academics and performance. In order to see prolonged results and to make something worth more than just being a novelty, the user must be able to establish a habit with the object. Only then can DMIs be worthwhile to performers.

Where does it go from here?

Even though, according to Perry R. Cooks’s first Principle for Computer Music COntrollers list, “Programmability is a curse,” many evaluators of the Slapbox showed interest in the ability to load samples onto the instrument (3). This improvement would be an interesting implementation that could prolong the life cycle of this system after the preset sounds have been exhausted by prolonged users. I’m excited to see where the next iteration is heading and hope more DMI designers prioritize durability in the way we see in the Slapbox.

References

- Boettcher, B., Sullivan, J., & Wanderley, M. M. (2021). Slapbox: Redesign of a Digital Musical Instrument Towards Reliable Long-Term Practice. NIME 2022. https://doi.org/10.21428/92fbeb44.78fd89cc

- Dobrian, C., & Koppelman, D. (2006). The E in NIME: Musical Expression with New Computer Interfaces. Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression, 277–282. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1176893

- Cook, Perry R.. “Re-Designing Principles for Computer Music Controllers: a Case Study of SqueezeVox Maggie.” New Interfaces for Musical Expression (2009).