Xyborg 2.0: A Data Glove-based Synthesizer

Hand-based motion-focused music systems like an earlier version of Xyborg quickly became my field of interest during my studies at IMV. There is just something ideologically captivating about freeing myself from standing in front of a keyboard looking like I am google searching something. Prototyping instruments involving some sort of data glove has a long history dating back to the 1980s. One of these early designs piqued my interest in particular: Michel Waiswisz’ first iteration of “The Hands” clearly influenced Xyborg’s design. I wanted to see how far I could take this first iteration concept while incorporating my own ideas, dependencies, and, well, limited knowledge. Really, my thought in the beginning was: “Can I play a synthesizer strapped to my hands while walking around?

From Paper to Prototype

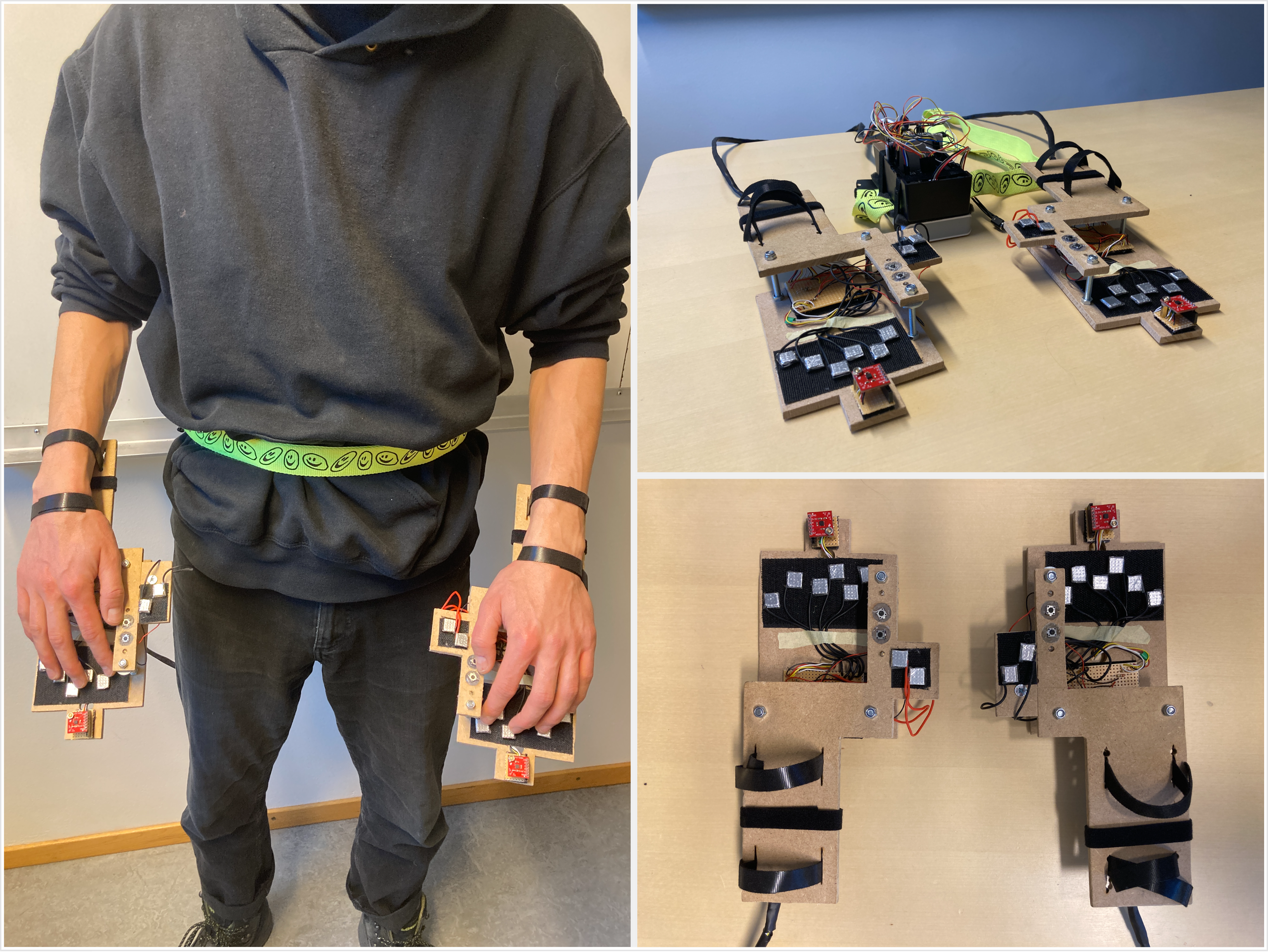

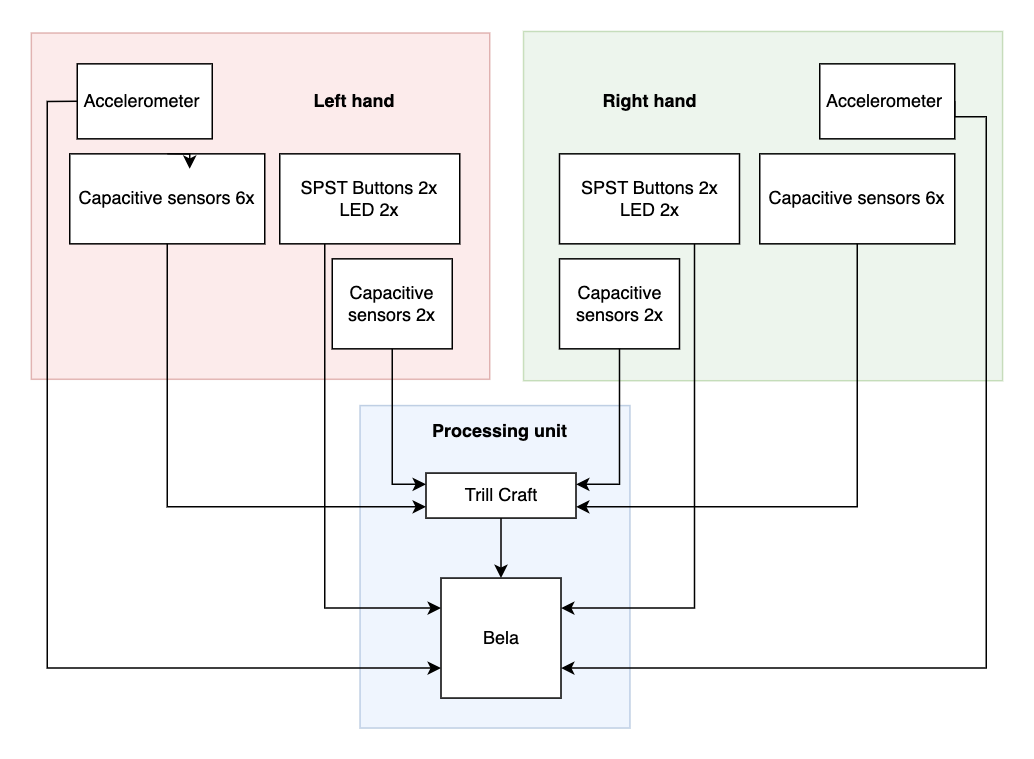

My system consists of two wooden frames, two accelerometer sensors, sixteen DIY capacitive sensors (eight for each hand) and four buttons + LED’s. All of this is connected via solid core wire with the brain of the system: my pure data sound patches run on a hardware system called Bela - a tiny powerful computer specifically designed for musical purposes. The Bela sits inside a plastic casing and is powered by a power bank. Everything is strapped around the waist. You are fully power-independent and mobile while wearing the instrument.

The mental model of Xyborg is indeed a keyboard with twelve keys, representing twelve steps in a chromatic scale. In addition to that, you have your movement control three effects: a lowpass filter, distortion, and modulation. Changing the octave range as well as effect on/off is provided by pressing additional buttons. Instead of using buttons as pitch keys, I opted to try a DIY design and build sensors. Capacitive touch sensing was the hottest candidate for that, and luckily, Bela supports that with the trill craft. The sensors are fairly simple. I cut 2x2 cm squares from a PCB board and wrapped it in aluminium tape. Then, I fixed a stranded wire between tape and PCB, on the conductive side of the PCB square. The thumb on both hands controls the buttons for effect on/off as well as the octave range touch sensors. But how do you manipulate effect parameters with motion?

Gesture-to-Sound (Manipulation)

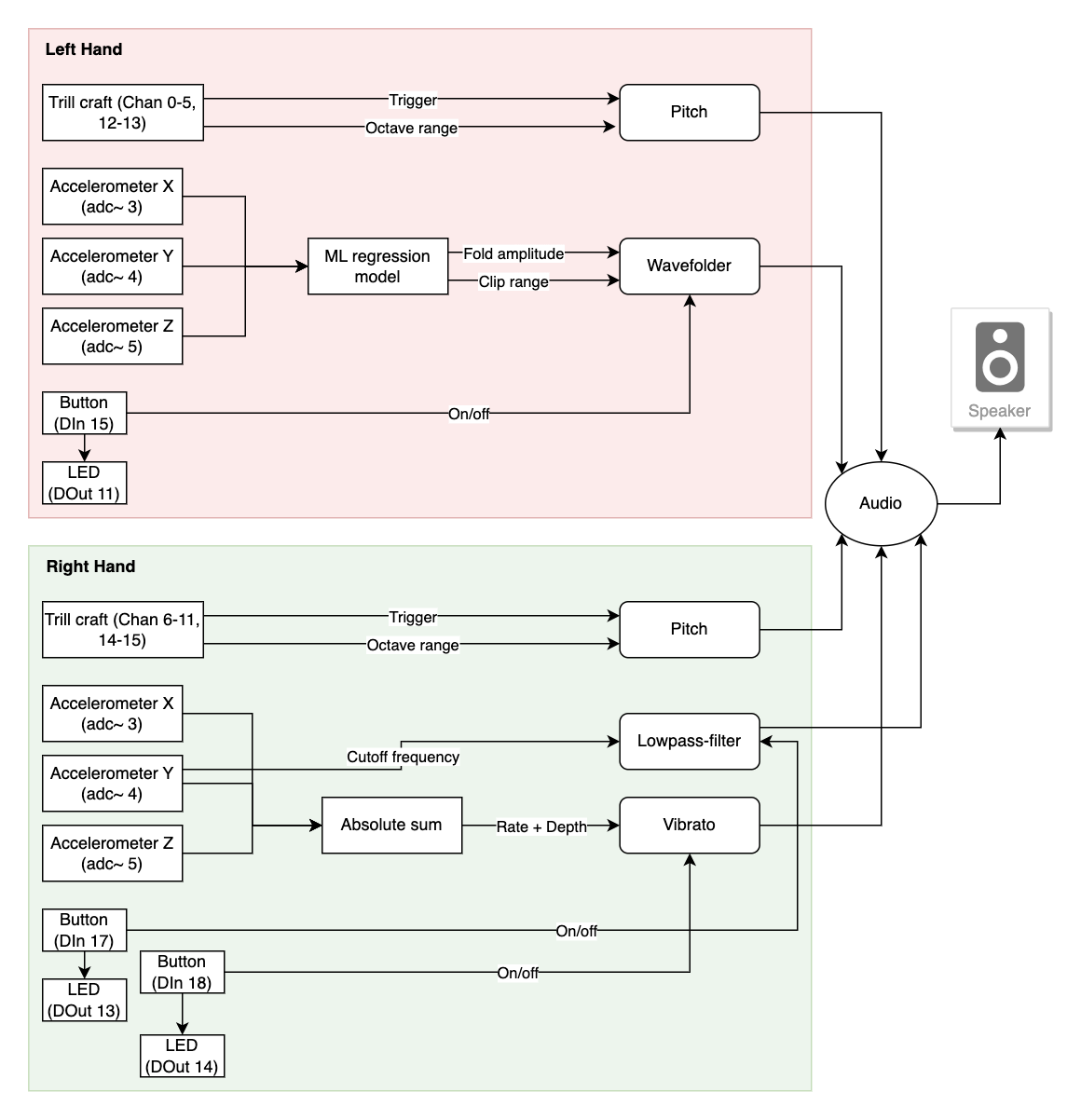

I installed a three-axis digital accelerometer on top of each frame. This sensor gives me acceleration data for x, y and z axes, and, to some degree, the orientation of these axes in a coordinate system. Now it’s only a matter of mapping this sensor data to effect parameters inside my software instrument. You can see the mapping and signal flow for each hand in the figure down below. To offer a degree of transparency for performer and audience, I tried to keep the mapping as simple and clear as possible. This means the instrument has an initial position - a pose with your arms completely relaxed. From there on, roughly speaking, the parameter space changes in such a manner that increasing the height of your hands ‘opens up’ the effects. The mapping for distortion is based on a regression machine learning model made possible with this awesome framework for pure data. I think the idea of a cloud is quite a fitting analogy to describe how the movement - sound connection works here. In a cloud you have regions with different densities - much like as in a musical parameter space based on a regression model. For the filter, the cutoff frequency is mapped to the pitch (y-axis) of the accelerometer. Simply moving your hand up increases the filter cutoff, essentially opening up the filter. The vibrato is mapped to the sum of all acceleration data of the left hand - the faster you perform a vibrato motion, similar to the same motion performed on a string instrument, the faster the vibrato will be.

Judgement Day

I am actually super satisfied with the sound of the instrument as well as effect manipulation capabilities. Controlling the filter cutoff and vibrato speed as well as moving through the distortion cloud all feels natural and intuitive. I would not go any further and include more features and effects, but rather focus on practice. Where the instrument is still clearly lacking is in the field of ergonomics and general design. First of all, it is hard to strap the system onto your arms all by yourself. Secondly, while playing around with it for roughly 5 hours total I could clearly see the downsides of my design. One of the biggest downsides is the exclusion of the thumb for playing a pitch key. My reasoning was that I would provide myself with greater flexibility in manipulating the sound if the thumb solely focused on control functionality. In the end, this does not make up for the missing fifth finger, especially when you are used to playing any type of key-based instrument. Subjectively, cognitive load actually increased for me since I had to re-map finger positions to pitches mentally from what I am used to on a commercial key layout. For the next prototype, I would simply erase the upper section of Xyborg and instead tilt it 90 degrees and mount it to the side of the base plate. I would then include a touch capacitor for the thumb while making sure that the control buttons and octave buttons are still in reach. Funnily enough, I also rarely used the octave range keys and rather stayed in the same octave. It is just too complex to find a desired pitch range fast enough for two hands. However, this gave me an interesting set of constraints. Instead of focusing on arpeggi or melodies over a wide range of notes, I intuitively focused on playing continuous notes and dissonances. This play style fits rather neat with the slow movements of effect manipulation. So I already developed a style!

Despite the apparent room for improvement I can clearly see potential for a long-term engagement with Xyborg. It is fun to use, feels very intimate while playing, and the mapping is complex enough to allow for skill development over time, in my opinion. If you want, you can check me out playing for a couple of minutes down below!