The Saxelerophone: Demonstrating gestural virtuosity

“Knowing the game” is often necessary when it comes to evaluating live performances, especially if it turns out that the performer in front of you is playing one of those totally wacky Interactive Music Systems (IMS)! In the NIME community , it’s quite common for these IMS to reflect a “short-lived expression of individualism” rather than a design intended for a wider audience (Vasquez et al., 2017). In fact, this is essentially due to their very nature, as IMS have the unfortunate tendency to limit the demonstration of virtuosity associated with acoustic instruments, since most of these systems operate a brutal separation between human action (i.e. gesture) and the sound production system.

Well, in the NIME community there’s even talk of a virtuosity crisis (Dobrian and Koppelman, 2006), and there’s actually a fair amount of concern about questions that deal with how IMS performances can be meaningful, perceptible and useful (Wessel and Wright, 2002, Schloss, 2003). It’s true that the concept of virtuosity in the field of IMS has often been associated with a large sonic palette, via the manipulation of synthesizers or the use of a whole host of samples (Cascone, 2002), that can be easily manipulated by the performer, without having to worry too much about the gestures involved (West et al., 2021). And that’s where the problem lies! Because, in order to recreate a relationship between human action and the sound production system, shouldn’t we first and foremost be interested in gesture as a sound-generating function?

The Saxelerophone

Well, I think so, and that’s why I created the Saxelerophone. This IMS is designed to take account of the performer’s bandwidth, given that “some players have spare bandwidth, some do not” (Cook, 2017), but also of the visual relationship between gesture and sound in a live performance. In this sense, the Saxelerophone’s main objective is to improve the demonstration of virtuosity, which often tends to be misinterpreted by the public when it comes to new musical instruments (Vasquez et al., 2017).

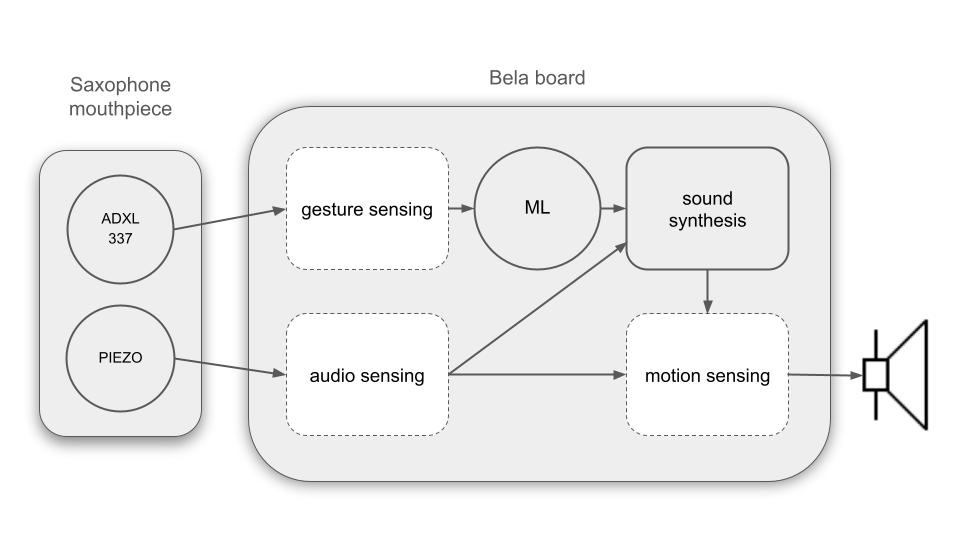

To achieve this, I conceived the Saxelerophone as a hyper-instrument (i.e. added additional sensors to the saxophone), “to give extra power and finesse to virtuosic performers” (Machover and Chung, 1989). On the one hand, it’s a simple, flexible system consisting of a contact microphone and a three-axis digital accelerometer, designed to be mounted on any reed instrument fitted with a ligature. On the other hand, it’s a system based on complex gestural control of sound synthesis, using robust machine-learning methods to learn static regression mappings, enabling the construction of a new expressive and creative sound space for developing gestural virtuosity.

The code, design files and technical documentation to replicate the system are available at the following address: https://github.com/joachimpoutaraud/saxelerophone.

Gestural control of sound synthesis

To saxophonists, it’s relatively easy to move their instrument around in space when playing. In fact, the smaller the saxophone, the easier it is, and that’s quite common to see this kind of demonstration at live performances.

So I thought it would be interesting to use the musical gestures of saxophonists, which have a certain capacity to visually accompany sound, in the sense that they are gestures in response to sound. These gestures have already been described as “sound-accompanying” (Jensenius et al., 2010) or “sound-tracing” (Godøy et al., 2006) gestures.

Three main objectives were defined for demonstrating gestural virtuosity with the Saxelerophone.

1. Audio sensing

For audio sensing, the aim was to collect acoustic information specific to the instrument with a contact microphone, so that it could be reused to generate new sounds. Here, I was interested in the fundamental frequency of the notes produced by the instrument, to be converted as the frequency of the carrier oscillator within the audio spectrum. Note that the contact microphone was also used to amplify the acoustic sound of the saxophone.

2. Gesture sensing

Next, a three-axis digital accelerometer was used to determine the saxophone’s orientation and changes in movement.

It was this sensor that first and foremost enabled me to define a physical relationship between the performer’s sound-accompanying gestures and sound synthesis control parameters (i.e. mapping). The mapping of gestures to sound synthesis parameters was then performed using machine learning. To do this, a regression algorithm was trained using an ANN framework for Pure Data called neuralnet to create a new sound space in which the performer could navigate to generate new interactive sounds. A schematic representation of the Saxelerophone’s mappings is shown in the diagram below.

3. Motion sensing

Finally, accelerometer data was integrated to estimate the instrument’s velocity. It is this last variable that allowed me to demonstrate a certain gestural virtuosity, since it enabled me to control the natural volume of the saxophone according to the volume of the synthesized sound. As the volume of the acoustic sound is inversely proportional to the synthesized sound, this means that the faster the instrument is moved in space, the more the sound will be synthesized, and vice versa. This allows the performer to play with two different musical palettes (acoustic vs. synthesized), depending on the speed of change of its position in relation to time.

Personal Reflections

As the designer of this instrument, I feel that the challenge of developing an instrument to demonstrate a new gestural virtuosity for the saxophone has on the whole been successful. The main technical challenges were to define the right frequency variation of the resistor-capacitor circuit (RC circuit) for use with the contact microphone, and to design a system that was flexible and adaptable to any reed instrument fitted with a ligature. After conducting a quick preliminary study involving 4 participants on the question of the audience perspective, the results obtained were largely positive. This confirmed my position on the subject, although the results were not compared to another IMS, nor to a different prototype version of the Saxelerophone.

As a performer of this instrument, I think first of all that a new approach to writing could be developed for this instrument, taking into account the performer’s gestures on the score. In addition, I think that in-depth work on the saxophone’s playing modes could be envisaged to deepen learning and engagement with the instrument. For the time being, the Saxelerophone relies on a single space for personal sound creation. Although it is possible to create new sound spaces ad infinitum, it would be beneficial to add new input variables related to the instrument’s own playing modes (percussive, blown, sung or multiphonic sounds) when training the model. This would give the performer greater expressiveness and a wider variety of sounds to match his or her virtuoso abilities.

Performing with the Saxelerophone

References

Vasquez, J. C., Tahiroglu, K., & Kildal, J. (2017). Idiomatic composition practices for new musical instruments: context, background and current applications. In NIME (pp. 174-179).

Dobrian, C., & Koppelman, D. (2006). The ‘E’in NIME: musical expression with new computer interfaces.

Wessel, D., & Wright, M. (2002). Problems and prospects for intimate musical control of computers. Computer music journal, 26(3), 11-22.

Schloss, W. A. (2003). Using contemporary technology in live performance: The dilemma of the performer. Journal of New Music Research, 32(3), 239-242.

Cascone, K. (2002). Laptop music-counterfeiting aura in the age of infinite reproduction. Parachute, 52-59.

West, T., Caramiaux, B., Huot, S., & Wanderley, M. M. (2021, May). Making mappings: Design criteria for live performance. In NIME 2021. PubPub.

Cook, P. (2017). 2001: Principles for designing computer music controllers. A NIME Reader: Fifteen years of new interfaces for musical expression, 1-13.

Machover, T. & Chung, J. (1989). Hyperinstruments: Musically Intelligent and Interactive Performance and Creativity Systems.

A. R. Jensenius and M. M. Wanderley. Musical gestures: Concepts and methods in research. In Musical gestures, pages 24–47. Routledge, 2010.

R. I. Godøy, E. Haga, and A. R. Jensenius. Exploring music-related gestures by sound-tracing: A preliminary study. 2006.