Review of On Board Call: A Gestural Wildlife Imitation Machine

Review of On Board Call: A Gestural Wildlife Imitation Machine

The On Board Call introduced in NIME 2022 is a handheld musical device designed to mimic and engage with wildlife sounds, such as bird or animal calls. Instead of just playing pre-recorded sounds, it uses microprocessor-based synthesis and sensors like an accelerometer and force sensor to allow users to interactively modify and perform with the sounds in real-time. Developed as part of the PLACE art-science project at Griffith University, its goal is to enhance appreciation for the eco-acoustic diversity of nature. The device is cost-effective and easily assembled from off-the-shelf components, making it ideal for community workshops focused on active listening and connecting with natural environments.

Hardware:

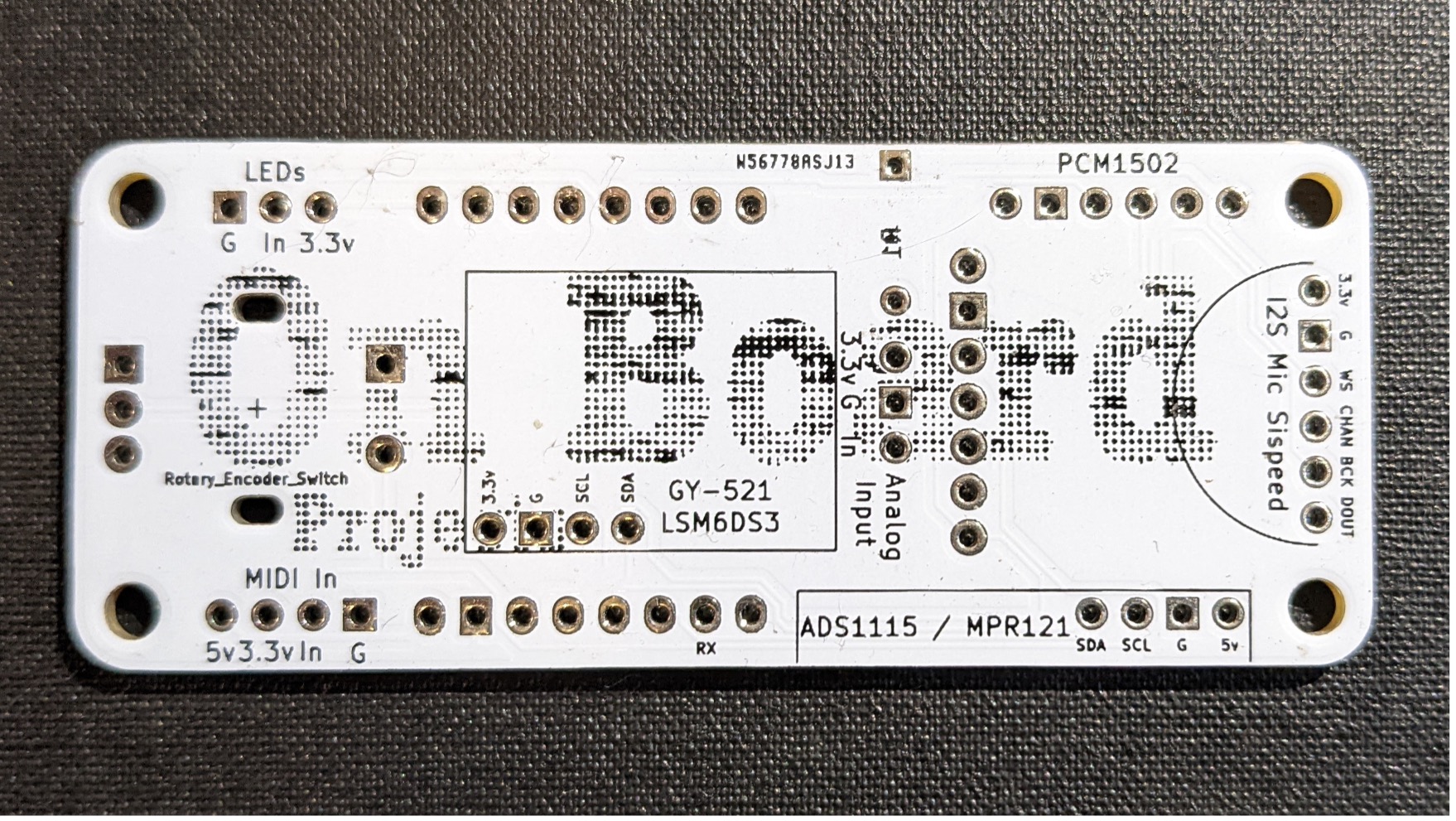

The musical interface uses an ESP8266microprocessor and an Adafruit MAX98357A audio board, powered by a battery case. The 6050-accelerometer detects gestures like pitch and yaw, communicating via the 12C protocol. Accelerometer data adjusts audio’s frequency and timbre, while a force sensor regulates volume. A rotary encoder with a switch allows volume and algorithm adjustments. The Adafruit board links to a loudspeaker for sound output. Components are mounted on a compact PCB, designed for durability and potential future adaptations.

Software and Mappings:

The software allows for the replication of calls with multiple sound components by duplicating the architecture. Presets define synthesis parameters for specific animals, but real-time pitch and timbre adjustments are performer-driven. Some presets automate rapid envelope repetitions to mimic certain call effects. The software, crafted in the Arduino IDE, utilizes the Mozzi library for sound generation. The software design began by analyzing calls of different animals from the Oxley Creek Common site. Spectral analysis highlighted the variations in pitch and timbre. This examination revealed that these sounds could be emulated using basic frequency modulation methods.

In the context of the Call software for the interactive music system, the mapping relationships appear to be oriented towards optimizing user interaction and simplifying synthesis architecture(Drummond, 2009).According to Hunt and Krik, and Miranda and wanderley. (Hunt and Kirk 2000; Miranda and Wanderley 2006), we can evaluate the Call software’s mapping as follows:

-

One-to-One Mappings: This is evident when specific gestures or positions of the device correspond directly to certain synthesis parameters. For instance, the device’s resting state has established values for pitch and timbre. Similarly, the rotary encoder’s default function is to control the master volume.

-

One-to-Many Mappings: The accelerometer’s x and y axes controlling both pitch and timbre can be considered an example of this. A single tilt or movement impacts multiple synthesis parameters simultaneously, enriching the resultant sound. Such a design decision helps in minimizing complexities that might arise with individual controls for each parameter.

-

Many-to-One Mappings: Loudness control in the software is an example, as it takes input both from the device’s position (orientation) and the force sensor, i.e., pressure applied by the user.

-

Many-to-Many Mappings: While not explicitly stated, the rotary encoder’s multifunctionality (adjusting synthesis parameters, selecting algorithm presets, etc.) suggests that its rotations and presses can influence a variety of parameters, making it a many-to-many mapping interface.

The use of sigmoid curves to provide stability near the device’s resting state indicates a deliberate effort to smoothen real-time mapping. According to Wanderley gesture data aquisation is “direct” and “alternate” in this case where sensors monitor the performer’s actions, capturing specific gesture features like pressure, displacement, and acceleration, with each variable typically detected by a distinct sensor, and alternate in a manner that it does not resemble any instrument (Miranda et al,.2006).

Trials and Evaluation:

As outlined in the project paper, the design was refined through numerous iterations and prototypes in both software and hardware. Field trials were also conducted with professional musicians in natural settings, primarily in ensemble setups alongside acoustic instruments during imitation and listening sessions. The focus of these trials was primarily on the design’s durability. However, the paper does not address the feedback received or any interaction with the musician group.

Furthermore, the paper notes consultations with birding communities. These sessions encompassed playing, comparisons, discussions, and analysis. The authors contend that birders, as expert wildlife listeners, offered invaluable insights that influenced the synthesis and gestural control aspects of the device’s design.

Usabilty and Engagement:

In contrast to prior systems that utilize fixed spectromorphologies, parameters, and envelopes, the approach discussed here ventures into the realm of dynamic spectral interaction. The On Call device, leveraging its microprocessor PCB audio system for sound synthesis, places a premium on user-friendliness and ease of use, even if it means compromising on imitative accuracy. Holland et al. explored the question of whether musical interaction should necessarily be simple (Holland et al., 2013). Emulation, as defined by imitative accuracy in this project, is brought into focus by Kesilar, who examines the challenge of addressing a well-known issue which in this case is imatation of wildlife tones(Keisler, 2001). This prompts an inquiry: Does this design approach risk diminishing user engagement? McDermott and peers suggest that long-lasting engagement often stems from activities that present initial challenges to novices(McDermott et al., 2013).

Sources

-

Brown, A. R. (Ed.). (2022). On Board Call: A Gestural Wildlife Imitation Machine. NIME 2022. https://doi.org/10.21428/92fbeb44.71a5a0ba

-

Drummond, J. (2009). Understanding Interactive Systems. Organised Sound, 14(2), 124-133. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355771809000235

-

Holland, S., Wilkie, K., Mulholland, P., & Seago, A. (2013). Music Interaction: Understanding Music and Human-Computer Interaction. In S. Holland, K. Wilkie, P. Mulholland, & A. Seago (Eds.), Music and Human-Computer Interaction (Springer Series on Cultural Computing). Springer, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-2990-5_1

-

Hunt, A., & Kirk, R. (2000). Mapping Strategies for Musical Performance. In M. M. Wanderley & M. Battier (Eds.), Trends in Gestural Control of Music. IRCAM–Centre Pompidou.

-

Keislar, D. (2011). A Historical View of Computer Music Technology. In R. T. Dean (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Computer Music (Oxford Handbooks online edition). Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199792030.013.0002

-

McDermott, J., Gifford, T., Bouwer, A., & Wagy, M. (2013). Should Music Interaction Be Easy?. In S. Holland, K. Wilkie, P. Mulholland, & A. Seago (Eds.), Music and Human-Computer Interaction (Springer Series on Cultural Computing). Springer, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-2990-5_2

-

Miranda, E. R., & Wanderley, M. (2006). New Digital Musical Instruments: Control and Interaction Beyond the Keyboard. A-R Editions.