The Tickle Tactile Controller - Review

The interactive music system I have decided to review is the Tickle tactile controller. The developers generously published two papers on it in 2019 [1, 2] and made their Pure Data patches available in a GitHub repo. One of their papers mentioned wanting to use the Bela board to create an embedded system under the Future Work section [1].

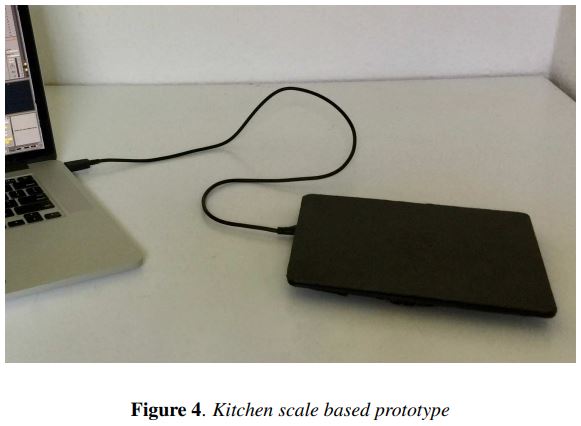

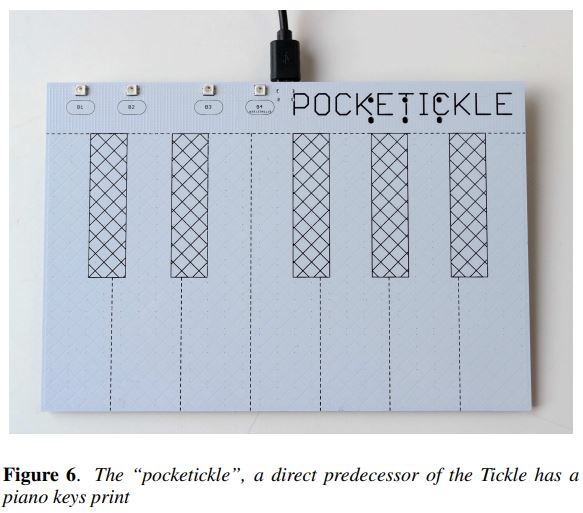

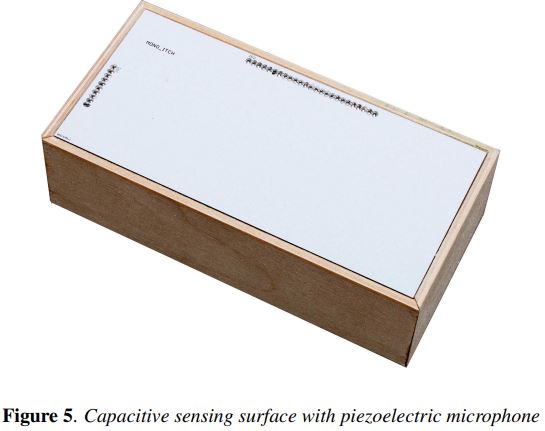

Like many digital instruments I have come across, the instrument design takes its initial inspiration from the piano, a fixed-key instrument. However, what struck me most was how different the prototypes were. They experimented with force-sensing (using a kitchen weighing scale!) before finally settling on capacitive sensing.

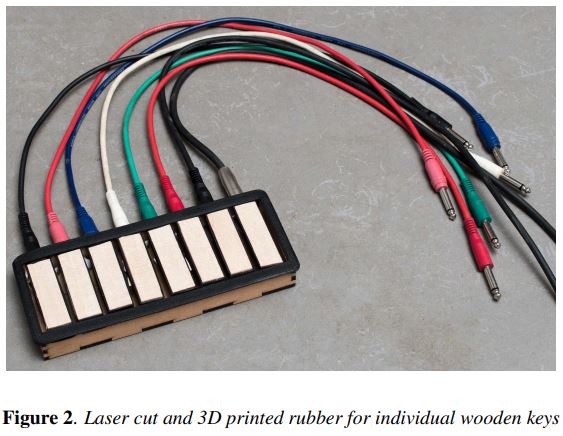

First prototype |

Second prototype |

Third prototype |

|

Fifth prototype |

Sixth (and final) product |

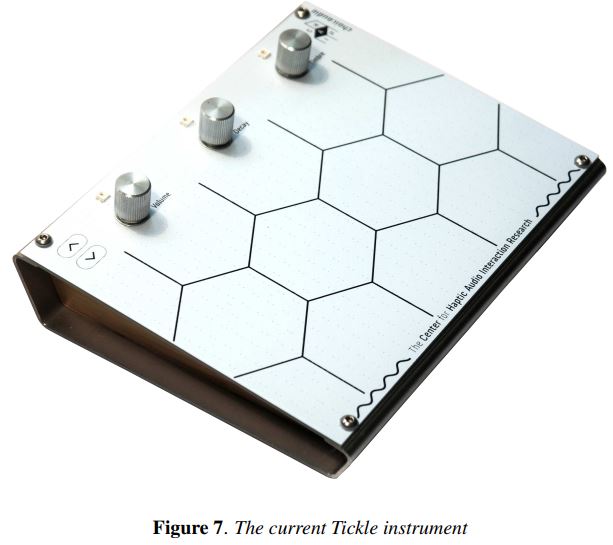

This IMS was meant to bridge the gap between the analog and digital worlds. In a YouTube interview, one of the developers mentioned that they wanted to move away from playing knobs or keys to “get a bit closer (to the sound-producing action)”. They have drastically updated their DO, FEEL, and KNOW ideas of interaction design [3]. As of the latest version, there is a piezo disc under the surface, which you excite by tapping and scratching with your fingers - or by bowing, and it lets you generate different resonances.

In the video, they demonstrate using the Tickle tactile controller with a separate new hardware component called the Waveguide. This stereo analog delay Eurorack module does Karplus-Strong synthesis - a method of physical modeling synthesis for plucked strings and percussive sounds. It is possible to re-trigger the sound before the initial sound has decayed completely, making it possible to achieve a somewhat polyphonic output.

Eurorack module - WAVEGUIDE (Image Copyright: synthanatomy.com)

Without the Eurorack module, they use synthesis algorithms in their open-source Pd patches. By interacting with the touch controller, the user excites the surface, sending a noise burst into a filtered delay line. They preferred to use hard, textured material on the surface to enhance the noise signal from a user interacting with the touch surface.

The approach to mapping differs from typical electroacoustic instruments because the sound control is now directly linked to physical actions instead of relying on abstractions of other technical parameters. In this sense, there is a direct mapping between the physical output from the touch surface of the Tickle and the input of the sound-producing model.

As Paine says, new performance practices arise with new instruments, and it is still crucial to have a notion of “liveness” [4]. The Tickle fits in very well with the physicality idea of actions leading to sounds through the secret sauce of control mapping. The performer has agency over when and how to make what sound, even though this agency might be less pronounced/evident than in an acoustic instrument such as the guitar.

Since the sound synthesis part is done with a Eurorack modular system, it is limited to one-to-one or one-to-many mappings, with many-to-many mappings offering challenges due to electrical reasons. However, simple Eurorack synthesis integrated with flexible control over mappings with the Tickle controller is a combination that can unlock lots of new possibilities.

From what I observed in another performance video, the Tickle tactile controller exudes several one-to-one mappings. Each hexagon on the touch surface triggers a specific sound. BUT, since this is a controller compatible with Pure Data patches, it is possible to create one-to-many, many-to-one, and many-to-many mappings as well. In addition to the touch surface, there are three knobs: volume, decay, and timbre. Volume is reasonably straightforward. Decay controls the decay time. Timbre, which is the rightmost knob, excites different overtones. The controller has excellent cross-compatibility. It works with audio and MIDI in a DAW (Ableton Live), Max/MSP, and Pd. They are building support for SuperCollider, too.

When tapped, the hexagons generate a discrete sound parameter; when the surface is rubbed, scratched, or bowed, it can be mapped to control a continuous parameter. Their Instagram page suggests you can also do wild stuff with it, like using a toothbrush to interact with the touch surface! That means infinite ways of interacting with it - so cool. It reminds me of the idea of Co-adaptation, where the user not only understands the system’s capabilities but learns how to modify it to their taste [5]. One should keep in mind though that the control parameters would still be fixed and these are what in turn enable (and also limit) the range of expressivity of the surface.

Still image from the IG video

Overall, this IMS allows for many natural and intimate interactions [6], with defined control over sound synthesis. The sounds created from this can be as familiar as the violin or percussion and also quite alien - still with a familiar analog touch.

One of the next steps for the developers of this IMS is to include real polyphony, so the ability to produce two sounds simultaneously (without the physical synthesis delay trick I explained earlier). They also want to incorporate pressure sensing and haptic feedback in their design. Currently, the primary feedback is visual, and the secondary feedback is sound. Haptic feedback would be a great addition since this is a tactile controller. This would make the Tickle feel more like an instrument, too. The devs also wanted to include analog circuitry inside the Tickle for sound synthesis. I don’t know if they still want to do this, though, because they did develop an entire Eurorack module to complement the Tickle… which in turn is a testament to backward compatibility in their design ideology (something Cook [7] mentioned as a design principle, too).

It is nice to see people make cool things and leave them as open source so others can learn from their process. Most interactive music systems don’t see the light of day after the prototyping stage, but it is inspiring that these guys from Chair Audio were able to develop an actual product with it. The fact that they continue to work on it shows that their IMS gained traction in the community!

References

[1] Wegener, C., & Neupert, M. (2019, July). Excited Sounds Augmented by Gestural Control. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Computer Music Conference, New York, NY (p. 5).

[2] Neupert, M., & Wegener, C. (2019, March). Isochronous Control+ Audio Streams for Acoustic Interfaces. In Proceedings of the 17th Linux Audio Conference (LAC-19) (p. 5).

[3] Verplank, B. (2009). Interaction design sketchbook. Online publication.

[4] Paine, G. (2011). Gesture and Morphology in Laptop Music Performance. In The Oxford Handbook of Computer Music. Oxford University Press.

[5] Holland, S., Mudd, T., Wilkie-McKenna, K., McPherson, A., & Wanderley, M. M. (2019). Understanding Music Interaction, and Why It Matters. In New Directions in Music and Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 1–20). Springer International Publishing AG.

[6] Wessel, D., & Wright, M. (2002). Problems and Prospects for Intimate Musical Control of Computers. Computer Music Journal, 26(3), 11–22.

[7] Cook, P. R. (2009). Re-Designing Principles for Computer Music Controllers: a Case Study of SqueezeVox Maggie. In Proceedings of New Interfaces for Musical Expression.

Fourth prototype

Fourth prototype