How to break out of the comping loop?

“Comping” is a term coined by jazz musicians, meaning accompaniment. Traditionally, this term is associated with musicians in the rhythm section, such as the pianist, bassist, guitarist or drummer, whose role is to accompany the soloist when the latter plays the theme of a jazz composition or standard, or improvises a solo. It is therefore necessary for jazz musicians to develop skills in different formations (duo, trio, quartet, etc.) in order to improve their ability to accompany a solo musician or to interact with the musicians of the rhythm section. This defines the very essence of jazz improvisation, which consists in spontaneously inventing solo melodic lines, or accompaniment parts, as part of a jazz performance.

Generally speaking, it’s not always possible for jazz musicians to rehearse as a group (i.e. difficulty in finding a rehearsal venue, difficulty in finding a schedule that suits everyone) and often means having to resort to alternative means of rehearsing alone. Loop pedals can be used to record a riff or chord sequence to create a “loop”. This enables musicians to play several tracks of music simultaneously. Nevertheless, this type of practice has the disadvantage of always playing the same content and generating the so-called “canned (boringly repetitive and unresponsive) music effect”, due to the systematic repetition of the recorded loop without any variation (Pachet et al., 2013).

Another possibility is to use “minus-one” recordings (i.e. Jamey Aebersold Play-A-Longs) to play a piece with a recorded professional rhythm section. However, this does not take into account the style of the soloist, which may differ considerably from that of the recorded musicians, and this does not allow for interaction as the recording is totally unresponsive.

The Reflexive Looper

Based on these observations, Pachet et al. (2013) proposed the concept of “reflexive interactions” in a system called the Reflexive Looper (RLR). This aims to create “copies of musical performances” in order to tackle the limitations of traditional musical systems, such as generating stylistically consistent material or enabling Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). RLR consists of a system for playing “copies of past musical performances” of oneself (Pachet et al., 2013a). In particular, this allows the system to develop a semblance of creative sense in order to generate an interaction between the musician and the system, based on the material produced by the musician. The aim here is to create enough of a transformation not to resemble direct imitation (Gifford et al., 2018).

Mapping

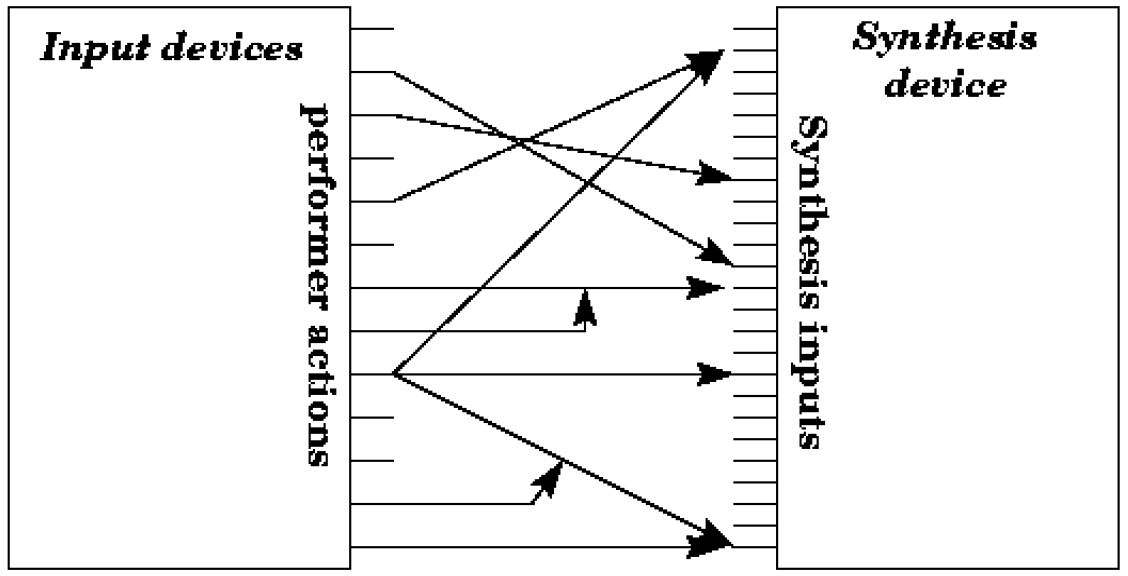

In order to allow the correspondence between parameter control and sound synthesis parameters, several types of mapping can be used (Hunt et al. 2000). On the one hand, the use of systems producing a mapping strategy through internal adaptations of the system thanks to prior training, and on the other, the use of mapping strategies defining relationships explicitly. In the case of the RLR, the mapping strategy is based on the supervised learning of a multi-modal classification model (i.e. Support Vector Machine). Here, the model is trained on MIDI signals produced by a “guitarist improvising with a Godin MIDI guitar on eight jazz standards with different tempos and rhythmical feels (Bluesette, Lady Bird, Nardis, Ornithology, Solar, Summer Samba, The Days of Wine and Roses, and Tune up)”.

Thus, from the system’s internal adaptations, it is possible to generate two principles:

- the principle of interaction based on feature extraction

- the principle of “other members”

In the first case, the system can extract audio features specific to the musician (i.e. RMS, peaks count, and spectral centroid) and re-use them to generate an accompaniment according to the style of the musician’s playing. In the second case, the system can differentiate the musician’s playing mode and interact accordingly. For example, if the musician improvises a solo, the RLR interacts by playing the rhythm section (bass and chords). And conversely, if the musician plays chords, the RLR interacts by playing a solo with a bass line.

Score Following

The RLR is based on embedded knowledge of the tempo and overall structure of the jazz standards chord grid. This requires the system to interact with the musician while taking into account the correct chord of the grid. This functionality refers to the concept of score following (Dannenberg 1984; Vercoe 1984), in which a system follows the progress of a live musician through a predetermined score, and “reacts’’ accordingly. According to Drummond (2009), this has the disadvantage of making the system more reactive than interactive, given that the system is initially programmed to follow the musician in all circumstances. So, although RLR can extract the features of the musician in real-time while applying an algorithmic transformation to generate “interactive” content, score following systems have been criticized as being “a perfect example for intelligent but zero interactive music systems” (Jordà 2005: 85).

Control and Expression

Finally, previous work has suggested that “the expressivity of an instrument is dependent on the transparency of the mapping for both the player and the audience” (Fels et al., 2002). The RLR has the advantage of being fully automatic and having no physical controllers (e.g. pedals). This eliminates the need for additional mental attention on the part of the musician, and allows greater availability for the expression necessary for jazz improvisation. Although the addition of physical controllers could eventually give more control over the audio generated by the RLR (Pachet et al., 2013), the intelligent and automatic interpretation of the material produced by the musician nevertheless enhances its expressiveness by ensuring that the mapping between input and audio generation is located at the appropriate level of structural detail (Dobrian et al., 2006).

References

Pachet, F., Roy, P., Moreira, J., & d'Inverno, M. (2013, April). Reflexive loopers for solo musical improvisation. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2205-2208).

Gifford, T., Knotts, S., McCormack, J., Kalonaris, S., Yee-King, M., & d’Inverno, M. (2018). Computational systems for music improvisation. Digital Creativity, 29(1), 19-36.

Hunt, A., Wanderley, M. M., & Kirk, R. (2000, September). Towards a model for instrumental mapping in expert musical interaction. In ICMC.

Dannenberg, R. B. (1984, October). An on-line algorithm for real-time accompaniment. In ICMC (Vol. 84, pp. 193-198).

Vercoe, B. 1984. The Synthetic Performer in the Context of Live Performance. Proceedings of the 1984 International Computer Music Conference (ICMC84). Paris, France: International Computer Music Association, 199–200.

Drummond, J. (2009). Understanding interactive systems. Organised Sound, 14(2), 124-133.

Jordà, S. 2005. Digital Lutherie: Crafting Musical Computers for New Musics’ Performance and Improvisation

Fels, S., Gadd, A., & Mulder, A. (2002). Mapping transparency through metaphor: towards more expressive musical instruments. Organised Sound, 7(2), 109-126.

Dobrian, C., & Koppelman, D. (2006). The ‘E’in NIME: musical expression with new computer interfaces.