Exploring Breath-based DMIs: A Review of the KeyWI

Introduction

The relationship between musician and instrument can be an extremely personal and intimate one. Contrastingly the nature of interacting with machines is often characterised as being the opposite; removed, cold, impersonal. Electronic instruments however, must always straddle this. Of interest to me currently is the use of breath as a control-interface for Digital Musical Instruments (DMIs). Its innate connotations of intimacy implying potentials for deep connection with an instrument.

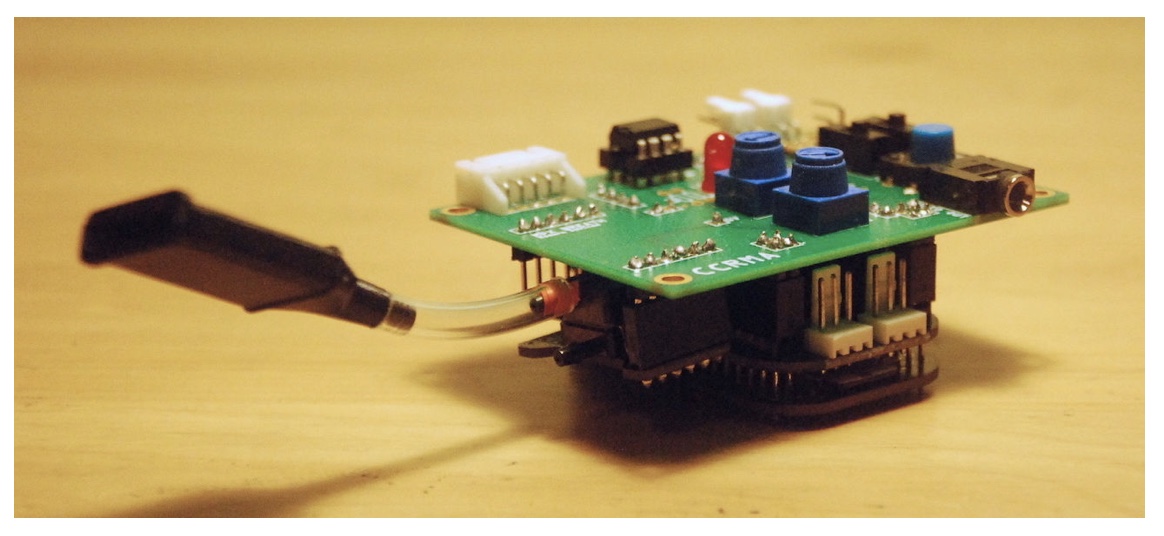

The KeyWI was shown at the NIME 2020 conference here. As set out in the paper, the KeyWI is intended as an accessible breath-based DMI modelled on the melodica. A more detailed breakdown of the instrument is provided on its website here as well as the open-source code and hardware on the Github repository A demo video of the instrument from its maker is shown below.

Technical and Self-Evaluation

As detailed on project website and paper, the system was evaluated at a technical level to assess how it compared to other breath-based DMIs and acoustic instruments. This looked at performance in dynamic range, attacks/transients, variance and expressiveness and pitch control interfaces. These results illustrate that in terms of technical hardware performance, the KeyWI’s breath interface performs more on-par with the response of acoustic breath-based instruments than comparative commercial DMIs.

In terms of the “accessibilty” of the instrument, as well as being a fully open-source project, the system has a keyboard for pitch information. This is justified as being a more familiar, standardised interface for musicians than the numerous equivilents in acoustic instruments. Finally, the KeyWI prides itself on its simple code-base, with the Faust DSP code for its melodica sound engine being a mere twenty-five lines long.

Critical Evaluation

Expressivity and accessibility are the key elements of this instrument’s self-identity. As such, in order to evaluate the system further I will draw on ideas of expressivity, engagement, virtuosity, immediacy and autonomy.

Beginning with “expressivity”, the key affordance for this is via the breath sensor. Examining the code across the various sound engines, this is mapped to amplitude and, where applicable across the sound engines; cutoff frequency of a low-pass filter, a modulation LFO and interplay between tone and noise. Though this demonstrates a one-to-many mapping seen as good practice, in actuality it is seemingly only ever mapped to amplitude and one other timbre parameter. This does correlate well with Wanderley et al.’s guideline for DMIs to, “require energy for amplitude”, though. With such mapping, many expressive techniques are open to the musician involving control over dynamics including, theoretically, tremolo.

As discussed, several design decisions were made specifically for the instrument to be easy to pick up and play. Blowing into the breath sensor appears intuitive and many musicians will be familiar with the keyboard interface. Furthermore, there are only controls for volume and switching between fixed preset sound engines. Seeing as the musician need only power the instrument and connect it to a speaker, there are relatively few obstacles to its usage. As such, the instrument has a very immediate feel to it.

Such decisions for the sake of immediacy may however impact the instrument’s potential for long-term engagement. Of relevance here are virtuosity, autonomy, as well as further dimensions in expressivity. Taken with these considerations in mind, the key bottlenecks are the chosen keyboard interface and the preset sound engines. While the keyboard interface does allow for immediacy, its chosen form is limiting by a keyboard’s standards. The keys are smaller than normal, and it covers only two and a half octaves. In other digital instruments, smaller keybeds will have controls for switching octaves up and down but that does not appear to be present here. Furthermore, requiring one hand to hold the instrument, makes two-handed playing impossible. Wanderley et al.’s guidelines state that two handed operation is ideal.

Regarding the KeyWI’s sound engine, again while this approach allows for immediacy, the simplicity of the sound engines and controls stands in opposition to the allowances digital synthesis offers over timbral properties and their opportunities for greater expressivity. What is notable however, is that these are also notably the limitations present in the original melodica. Indeed, one of KeyWI’s sound engines (present in the demo video) is an emulation of the melodica itself. This calls into question justifications for modelling DMIs on existing instruments to such a degree. Why build an emulation of something when the thing itself is so readily (and cheapily) available?

Though the demo video definitely displays musical competence, it is not hard to imagine an experienced musician reaching the instruments limitations relatively quickly. This can impede on the perceived autonomy of the musician, whereby the human’s capability outstrips that of the instrument. Furthermore if an instrument feels limiting to a musician in this way, can it be said to be truly expressive? Taken together, these can notably impact the likelihood of an instrument’s potential long-term usage.

Conclusions

Having outlined the trade-offs present which may limit the KeyWI’s long-term usage, it is important to note that this is not stated as a goal of the instrument by its maker. Future work could be justified to allow for a greater range of pitch and timbre control as well as a more sophisticated sound engine. Though, if the instrument’s desired goal is immediacy and accessibility over longevity, that too is valid.

Where the KeyWI is most notable is in the potential of its breath sensor. That tests of the sensor show it performing on-par with acoustic wind-based instruments implies great potential for usage in other instruments.