Why Your Exhibit Tech Failed (and how to fix it)

You had a great idea for an installation, convinced your stakeholders of said idea, took it through design and execution, only to realize that it doesn’t perform as intended. Why, you think to yourself after months of hard work, are visitors not using your installation? Why is the client unhappy? Why do people not understand how to use it? It’s so simple!

Chances are it’s not a bad installation at all. You might just disagree with yourself, the visitors, and your department or client about their needs and wants. The reason for this disagreement is always the same: you didn’t lay the project foundations early enough. Or worse, you didn’t lay down any foundations at all.

Asking The Right Questions

It is rarely a good idea to jump into a project and just start solving the most apparent problems. If you don’t spend time diagnosing, how confident can you really be that you’re solving the correct problem? Maybe you’re doing the right thing, but maybe not, and I probably won’t have to tell you that leaving the success of a project to chance is a bad idea.

Why should this project exist?

Installations can be commissioned by a third party, be part of a public funding deal, be requested by visitors, or be requested by an exhibit. These are not good enough reasons by themselves to create an installation. They will not guide your decision making, nor will they ensure a successful project. Sometimes these commissions come with a set of requirements. It’s important to understand the basis for those requirements and, if that basis is unreasonable or unrealistic, work with the stakeholders to create a better frame for the project.

Is this truly a change for the better?

Have you ever made a change to a product because you thought it was what your boss wanted when they really had something else in mind? Have you been stuck making minor changes because your client just isn’t happy with the result?

Stakeholders often request a feature or installation without having a reason beyond that they want it to exist. Other times they do have reasons, but they are unable to articulate those reasons in a way that’s easily digestible, and you spend an unnecessary amount of time finding common ground. This might be true for you as well. Your gut might say yes to a new idea but, while there is value in gut feelings, take a step back and see how a change relates to your goals.

How do you know if the project is successful or not?

Goals and evaluation go hand-in-hand. You cannot accurately evaluate the success of a project unless you set highly specific goals during the outset of your project. Worst case scenario, you will evaluate the project based on the wrong criteria and think the outcome is better or worse than it is. So, what do you do?

The MUSETECH Framework

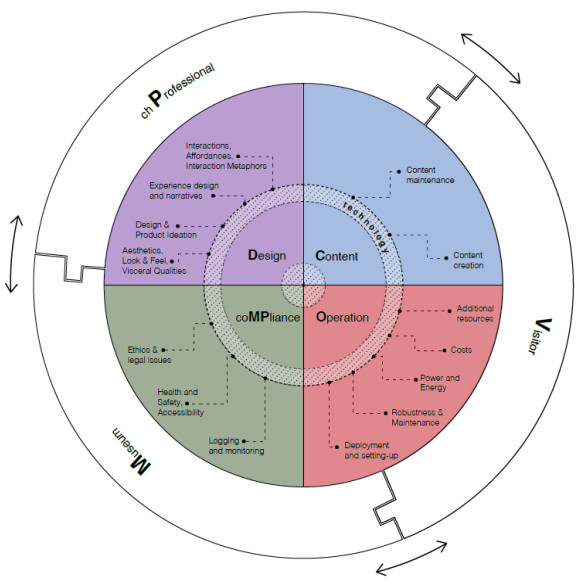

Developed by Areti Damala, Ian Ruthven, and Eva Hornecker, the MUSETECH model provides a strong foundation for judging the performance of technology. While intended for museums, any exhibition, gallery, or experiential learning center will benefit from this model, the only difference is terminology. This tool will speed up your decision-making process and give you the means to justify your design and implementation choices.

The model lists 121 criteria serving to guide you in your quest to understand what works and what doesn’t work about your installations and exhibit technologies. These criteria are grouped into 4 categories:

- Design: These criteria will help you make mindful design choices and articulate why these choices were made.

- Content: These criteria are concerned with the kinds of tech curators and establishments use to create and maintain content, but also visitor-personalized or visitor-created content.

- Operation: These criteria focus on resource requirements, installation, and maintenance of the installation.

- Compliance: These criteria deal with accessibility, health, safety, ethics, and potential legal issues.

These categories can in turn be approached from 3 different perspectives:

- The Visitor: Whomever is likely to attend the exhibition, the end users.

- The Cultural Heritage Professional: Outside of museums, I would call them curators or operation managers. They will be interacting with the same tech daily.

- The Museum (or exhibit/gallery/learning center): They have a unique understanding of their own purpose and how they envision the future of the establishment.

Work together with your stakeholders to select criteria and do so early in the development process to minimize misunderstandings and waste of resources.

Selecting Appropriate Criteria

The model presents a heap of criteria to choose from, but in reality you will rarely have the resources to fulfill each of them. Write down every criterion you think is relevant, then eliminate half of those with your main stakeholder to determine what’s truly important. What you’re left with is common criteria to measure your project against, giving you leverage to eliminate requests that do not support the goals of the project and more power to make changes that do, saving both time and money. If your only criterion is to promote social interaction and a feature request or design choice does not support this criterion, it is a poor use of resources.

Additional Readings

For a deeper understanding about this framework, I highly recommend reading the original article. If you just want to get started, check out the MUSETECH Companion for a comprehensive list of criteria.