The algorithmic note stack juggler

When I sat down to start this project, I was staring blankly at the collection of wires, buttons and various un-identified electronic components I had been given, and my 8 year old son came over to ask what I was doing.

“Well, my project is to build some sort of musical instrument. Something that will make beepy noises I expect” I said.

“Ah, so like note-blocks in Minecraft?”, he replied.

It was at this point that the idea was born. Or, well… stolen?

For those of you unfamiliar with Minecraft and its note-blocks, each tap on a note block steps through the notes of a scale. Emil and I realised that if we lined up several note blocks and each tapped on different blocks in a random order, it started to sound quite interesting. With some practice, we could generate some lovely melodies. But you wouldn’t exactly call our blocks an expressive musical instrument… or would you?

Conduits vs Collaborators

One view on musical instruments is that they are conduits through which ideas and meanings can be passed. The idea is that expressivity is paramount, and there should be as little as possible in between the musician and the expression of their ideas. Our Minecraft blocks probably wouldn’t rate that highly as a musical instrument from this viewpoint - you tap them, a note comes out. We don’t even get much choice in which note comes out - they simply run through a scale.

There is an alternative way to view musical instruments however. What if an instrument is looked at as more of a musical collaborator, a tool the musician works together with to create musical ideas? This idea of shared control between a musician and an instrument was first explored by Joel Chadabe in the 1960s and 70s. He developed an approach he would later call ‘interactive composition’, a “performance process wherein a performer shares control of the music by interacting with a musical instrument” (Chadabe, 1984). Drummond (2009) wrote that these interactive systems have the potential for variation and unpredictability in their response, and depending on the context may well be considered more in terms of a composition or structured improvisation rather than an instrument. From this perspective, our Minecraft blocks could be considered an interactive system, and I quickly set about building my own version with a Bela, breadboard and a ton of wires, buttons and LEDs.

The build

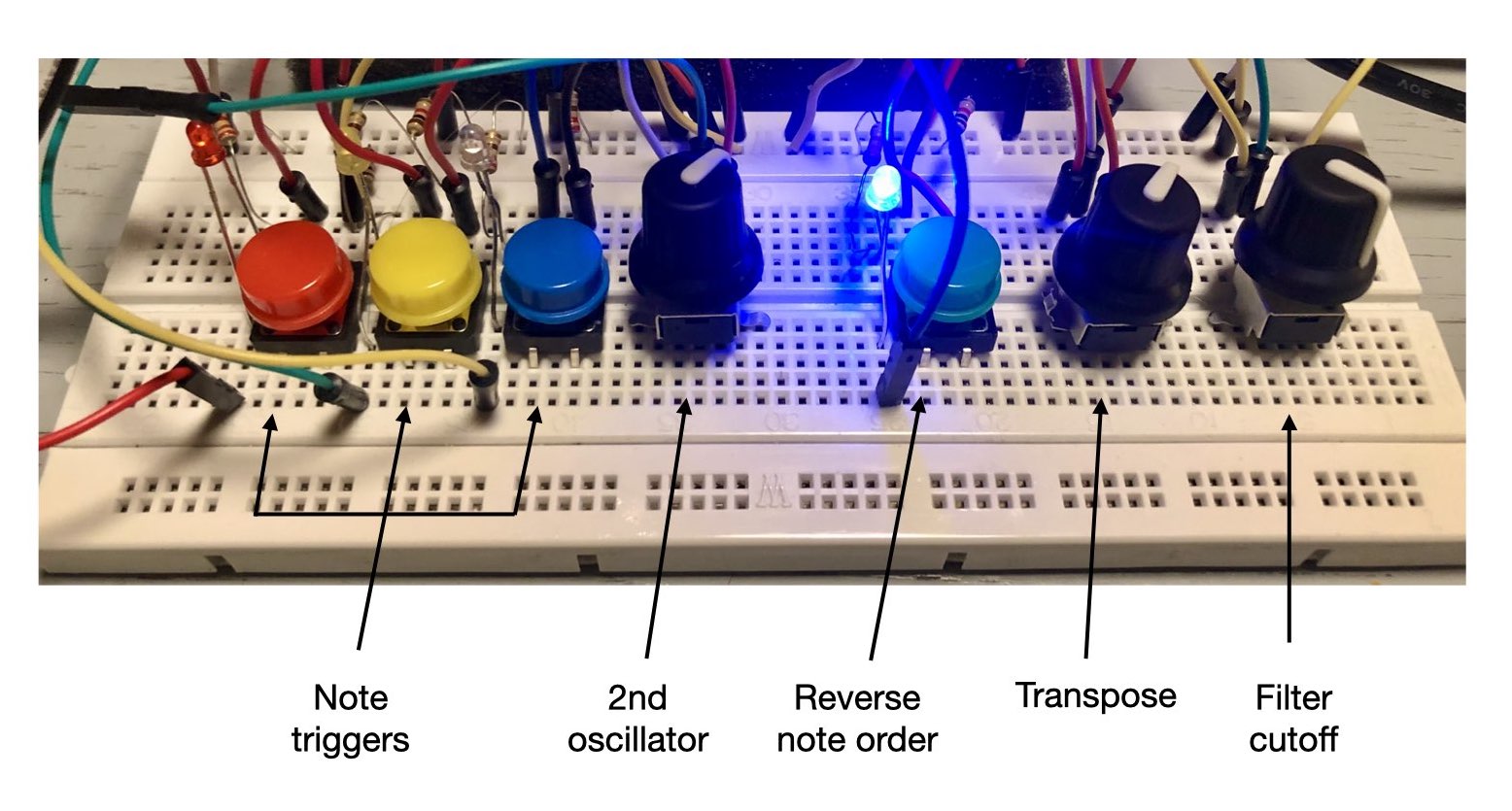

The main idea was to have 3 stacks of notes which could be triggered independently using clicky buttons. Each note stack would consist of different chord tones - 1st and 5th for the first stack, 1st, 3rd, 5th and 7th for the second, and 1st, 3rd and 7th for the third. I also added controls to manipulate the note stacks, including a button to reverse the note order, and a pot that would allow for transposition of the chord tones. For tonal variation, I added a filter cutoff knob, and a knob that brought in a second oscillator.

The sound generation part was written in csound, and consisted of 2 oscillators - a square wave and a triangle. The square wave would be the main oscillator, with the triangle adding the bass notes, following its own related note stacks of firsts and fifths. The oscillators are then run through a Moog ladder filter, a delay and a reverb. There is limited processing power in those wee Belas, especially when you start throwing around ladder filters. To keep things under control, three csound instruments were used. The first handled the controls and managed the note stacks, a second handled the sound generation, and a third master instrument added the filter and effects.

Performance

Here is the Algorithmic Note Stack Juggler in action (and yes, I know its a terrible name, but no-one was forthcoming when I asked for suggestions at the beginning of my presentation).

References

Drummond, J. (2009). Understanding Interactive Systems, Organised Sound, Cambridge Core. https://www-cambridge-org.ezproxy.uio.no/core/journals/organised-sound/article/understanding-interactive-systems/BF81A560B5C9D96355BC400065C7A1DF

Mudd, T. (2019). Material-Oriented Musical Interactions. In S. Holland, T. Mudd, K. Wilkie-McKenna, A. McPherson, & M. M. Wanderley (Eds.), New Directions in Music and Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 123–133). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92069-6_8

Chadabe, J. (1984). Interactive Composing: An Overview. Computer Music Journal, 8(1), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/3679894

Dahlstedt, P. (2018, February 22). Action and Perception. The Oxford Handbook of Algorithmic Music. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190226992.013.4