Musings with Bela

For my project in the Interactive Music Systems course, I decided to work with a portable EEG reader and a Bela coupled with an accelerometer and potentiometers. Little did I know how much of a challenge it is to join both software and hardware within an interactive package.

Inspiration

Coming from a undergraduate degree in cognitive science, I’ve always wanted to work with (read hack) an electroencephalogram (EEG) for some kind of artistic performance or instrument. While I have worked with a more traditional systems that require head-caps and conductive gel, I have never had the opportunity to test out some of the many different portable systems that have come out in the last decade. After reaching out to Alexander Jensenius, I was able to borrow a system from a researcher at RITMO - which I’ll cover later in the hardware section.

Artistic examples

In addition to my personal interest in finding an artistic meeting point between cogsci and MCT, I was also inspired by a number of performances and musical systems that employed EEG technology.

The first of these was Alvin Lucier’s “Music for Solo Performer” (1965) which was a landmark piece not only for its use of an EEG but sonification generally. Lucier had mapped the voltage potential from his electrodes into low-frequency tones that were able to excite percussive instruments in front of him.

The second performance that offered insights in using EEG’s in a sonic environment was Ouzounian et al.’s Music for Sleeping & Waking Minds (2011-2012). In their piece, they asked multiple participants to wear EEG sensors as they spent a night in a collective slumber. Over the course of the night, their brain waves (in passing through the various oscillatory states of sleep) were represented in sound and light.

In addition to these, there were a number of other interesting takes on EEG sonification such as MoodMixer (Leslie and Mullen, 2011), a collaborative installation where two participants navigate a shared musical space via EEG as represented by a 2D visual space. Another implementation comes from the Multimodal Brain Orchestra (Le Grouz et al., 2010), a collection of musicians whose sheet music was generated on the spot as a product from a reading of their collective cognitive response. And recently, Chris Chafe worked on sonification of seizure data recorded from EEGs, providing an illumination of hidden neural activity.

However, in all of these examples, it’s not obvious what the sensor data is actually being mapped to - a confusing experience from both the audience as well as someone trying to find inspiration for an IMS of their own. For a much more clear framework on how one would go about building and evaluating an IMS, I turned to the literature.

Academic support

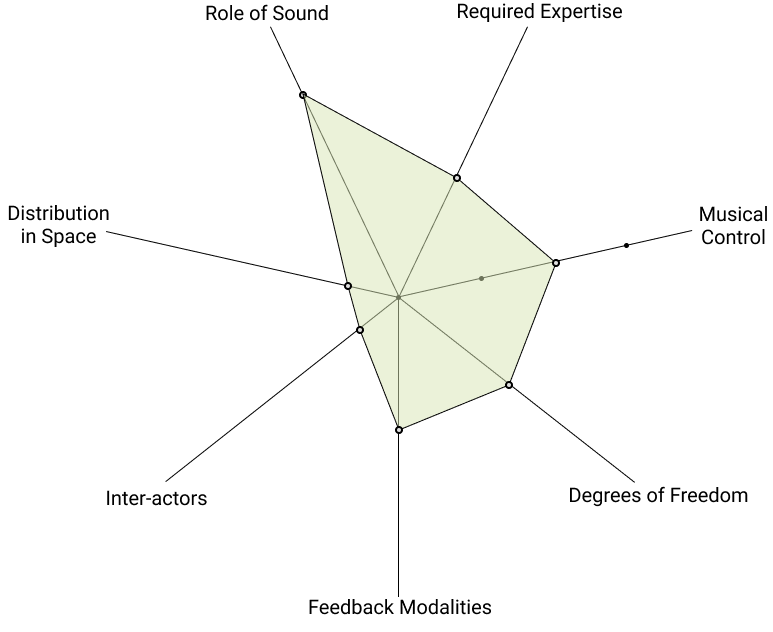

Two articles held my interest during the time I spent conceptualizing and designing my system, the first from Birnbaum et al. In their article Towards a Dimension Space for Musical Devices, the authors lay out a visual representation for describing aspects of IMS (Birnbaum et al., 2005). They identify 7-axes that might characterize new interactive music systems and in parallel, provide some representative space of which to locate an author’s proposal for their own IMS.

- Required Expertise

- Musical Control

- Feedback Modalities

- Degrees of Freedom

- Inter-actors

- Distribution in Space

- Role of Sound

These principles were helpful as a means of comparing my proposed instrument against others but also for a class of features to focus on as I developed it. For Musings with Bela, this is how we might visualize its capacity as an instrument:

The second paper, A Framework for the Evaluation of Digital Musical Instruments by O’Modhrain takes up a similar issue with the absence of well defined lenses through which we can consider, criticize and explain a musical instrument (O’Modhrain, 2011). O’Modhrain suggest that taking the perspective of not only a musician or designer when building an IMS, but also that of an audience member or even a manufacturer. These novel perspectives force an author to consider their instrument from angles that are not typically confronted until after the instrument has been built. In both articles, it is clear that building a musical interface is a project whose treatment must be considered with others in mind.

Hardware

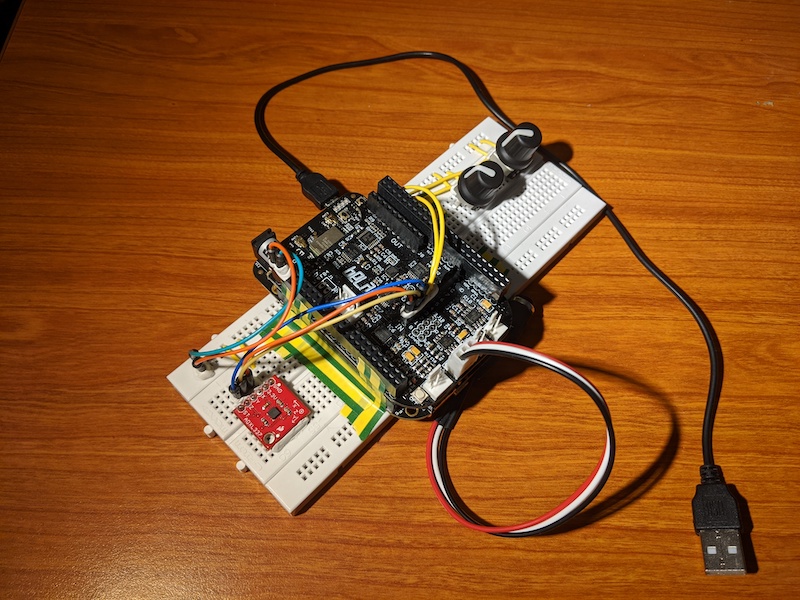

The device actually made use of the breadboard it was wired to as a frame to hold and rotate the device. The Bela was placed in between the accelerometer and two knobs, allowing for it to easily sit in one’s hands. The idea was to keep the design uncomplicated as the EEG might require the performer to have their eyes closed.

A Muse (2016) portable eeg headband, graciously borrowed from RITMO, was another major hardware device incorporated within my IMS. I had read through my preliminary research that this device might be easily hackable. Imagine my sadness after finding out all developer resources for the device were discontinued (ARJ you liar!). Unbroken, I pushed forward and ended up modifying a completely unknown Python package to finally interface with the device.

Nevertheless, the device’s specs are quite impressive with 4 electrodes recording at 256Hz and an all-day battery life (no joke). Unfortunately, the fact that the device streamed through Bluetooth meant that my laptop would necessarily be involved (I wouldn’t dare attempt it on the Bela (Okay, maybe if I had another week!)).

Software

Interpolating between tables with an accelerometer

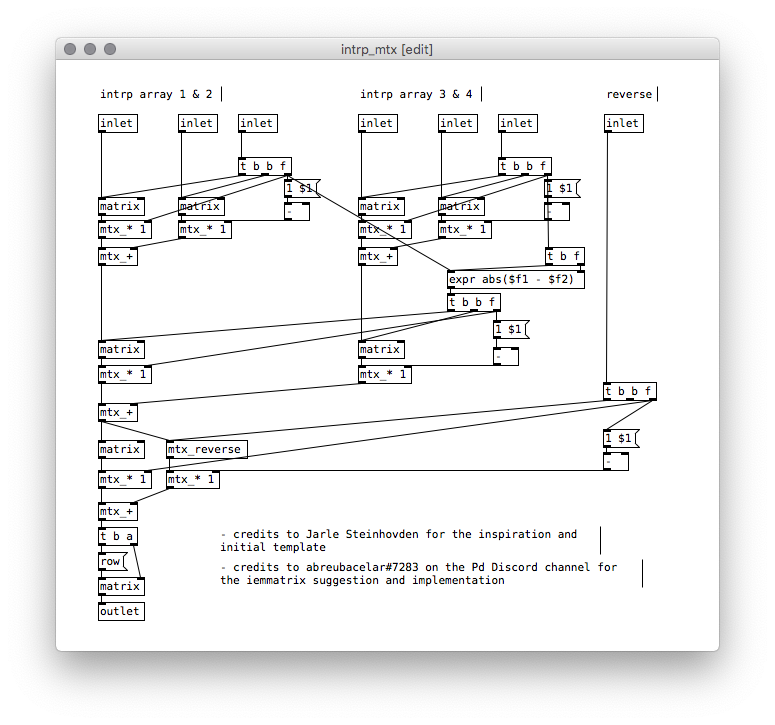

At the core of my system was a method for interpolating between short audio grains. Audio files were read into an array of 1024 samples and these arrays were then interpolated using the external iemmatrix. More typical methods of reading through arrays would be to step through each index and read the sample, apply whatever operation you wanted and then store it. In my case, however, I wanted to tie the accelerometer to degree each sound file is interpolated into one another (via arrays) which makes it challenge to read through these arrays sequentially when the sample rate of change needs to be very fast. iemmatrix instead, allows for operations to take place on the array as a whole (like numpy vectorization) meaning this is a much more efficient method of morphing between these arrays.

Upon reflection, another alternative would be to get two readings, do the matrix operations, and slide between them with a [line] object. As I was looking into this, this is an external (list-abs) that allows for linear interpolation between lists. However, this might be a slightly more costly object to use - perhaps a combination of both techniques would have worked best.

The two physical knobs control an oscillator to read the resultant table (a morphed sound grain) into the DAC. These knobs are also read at audio-rate but the operations they control are far less complicated. In Musings with Bela, these knobs serve as tuners for the synth that can explored (sonically) by rotating the device.

Reading arrays and remaining calm

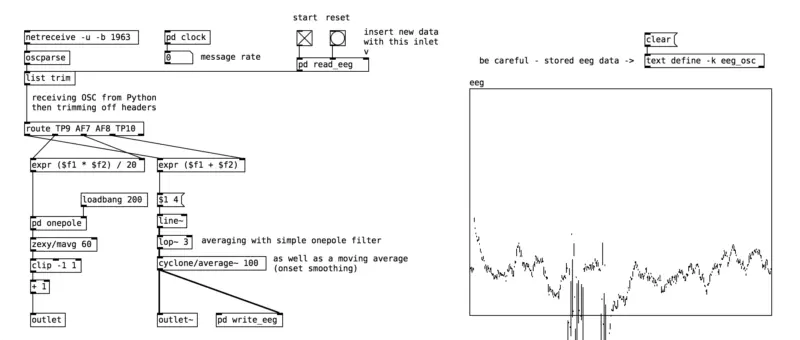

Finally, the last piece to my glorious IMS puzzle, the Muse! As I mentioned, this device was tricky, thorny, and a general struggle to work with, especially considering I had to set the Bela up as a WiFi hot-spot to pass the samples from the Muse, to my PC and then off to the Bela.

Another major piece of working with the Muse was actually testing to see the behavior of the electrode readings, if they are consistent, their fluctuations, and whether or not I would be able to reliably reduce the noise and relative intensity. I made a subpatch to test for this reason, allowing me to record and playback samples from the Muse even without its connection.

Musings with Bela takes this EEG stream and modulate the amplitude of the read table so that, in theory, a wandering, active mind would lead to a disrupted synth. The configuration was technical to say the least and, in retrospect, something I wish I had tackled earlier in the building process so I could use the EEG signals in a more complex mapping.

Reflections

Building an IMS is a whirlwind of an experience and one that is especially difficult to achieve in two weeks. Working with hardware and software turned out to double the time I expected any individual task would take. However, I feel like I had successfully built an interesting system that touched on my history in cognitive science and applied it within this an acousmatic environment.

Here is my short, final performance for MCT4045.

And my final presentation can be found below as well!

References

Birnbaum, David, et al. Towards a Dimension Space for Musical Devices. 2005.

Fan, Yuan-Yi, and F. Myles Sciotto. ‘BioSync: An Informed Participatory Interface for Audience Dynamics and Audiovisual Content Co-Creation Using Mobile PPG and EEG.’ NIME, 2013, pp. 248–251.

Hamano, Takayuki, et al. ‘Generating an Integrated Musical Expression with a Brain-Computer Interface.’ NIME, 2013, pp. 49–54.

Le Groux, Sylvain, et al. ‘Disembodied and Collaborative Musical Interaction in the Multimodal Brain Orchestra.’ NIME, 2010, pp. 309–314.

Leslie, Grace, and Tim R. Mullen. ‘MoodMixer: EEG-Based Collaborative Sonification.’ NIME, Citeseer, 2011, pp. 296–299.

O’Modhrain, Sile. ‘A Framework for the Evaluation of Digital Musical Instruments’. Computer Music Journal, vol. 35, Mar. 2011, pp. 28–42. ResearchGate, doi:10.1162/COMJ_a_00038.

Ouzounian, Gascia, et al. ‘To Be inside Someone Else’s Dream: On Music for Sleeping & Waking Minds’. New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME 2012), 2012, pp. 1–6.

Parvizi, Josef, et al. ‘Detecting Silent Seizures by Their Sound’. Epilepsia, vol. 59, no. 4, 2018, pp. 877–84. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/epi.14043.

Straebel, Volker, and Wilm Thoben. ‘Alvin Lucier’s Music for Solo Performer: Experimental Music beyond Sonification’. Organised Sound, vol. 19, no. 1, Cambridge University Press, Apr. 2014, pp. 17–29. Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/S135577181300037X.

Wu, Dan, et al. ‘Scale-Free Brain Quartet: Artistic Filtering of Multi-Channel Brainwave Music’. PloS One, vol. 8, no. 5, 2013, p. e64046. PubMed, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064046.