Algorytme

Introduction

Over the past few months, we have been working on a project for ACX Music aimed at generating personalized playlists based on emotional states, specifically designed for therapeutic and clinical purposes. The overall project goal was to develop a novel computer-based application that promotes mental health and well-being based on modern-day music therapy research. The application/system we propose seeks to accurately predict musical preferences by collecting emotional data through user-profiles.

In this post, we will talk briefly about Music Therapy before discussing our proposed solutions, development process and some challenges met.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Music Therapy

- User Interface

- Back-end System Design

- Challenges

- Ethics and Privacy Issues

- References

Music Therapy

Before developing an app that was meant to be used in music therapy, we had to go through some literature to understand what music therapy really is, and how music therapy has been used for purposes that our app will cover. Music therapy is a broad field; a big discipline with many practices and usages. Music therapy has been defined as “Development and change through a musical and interpersonal collaboration between therapist and client” (freely translated from musikkterapi.no). The other definition defines music therapy as an academic discipline: “The study of the relationship between health and music” (ibid.).

Fairly anyone can benefit from music therapy in some sort of manner, but perhaps the most common practice is music therapy used in interaction with people with learning disabilities, mental illnesses, dementia, etc. Often here, the active approach (Trondalen & Oveland, 2008, p. 437) is used, when the clients are actively engaged in musicking together with the therapist.

The app we are developing falls into the other main category of music therapy: The receptive approach (ibid.). The receptive approach involves the act of listening to music. Studies have shown that music listening could reduce anxiety before hospital procedures (Gillen et. al., 2008) and reduce pain during childbirth (Browning, 2000), but the most documented approach has traditionally been to use music for relaxation (Trondalen & Oveland, 2008; Ruud, 2010; Grocke & Wigram, 2006). It’s also commonly known that people use music to get in the right mood for different kinds of situations, e.g. for exercising.

The goal for the app we are developing has been to involve any kinds of potential music therapy purposes into the same system. That’s how we came up with the idea of using interpolation between different emotional states induced by music.

User Interface

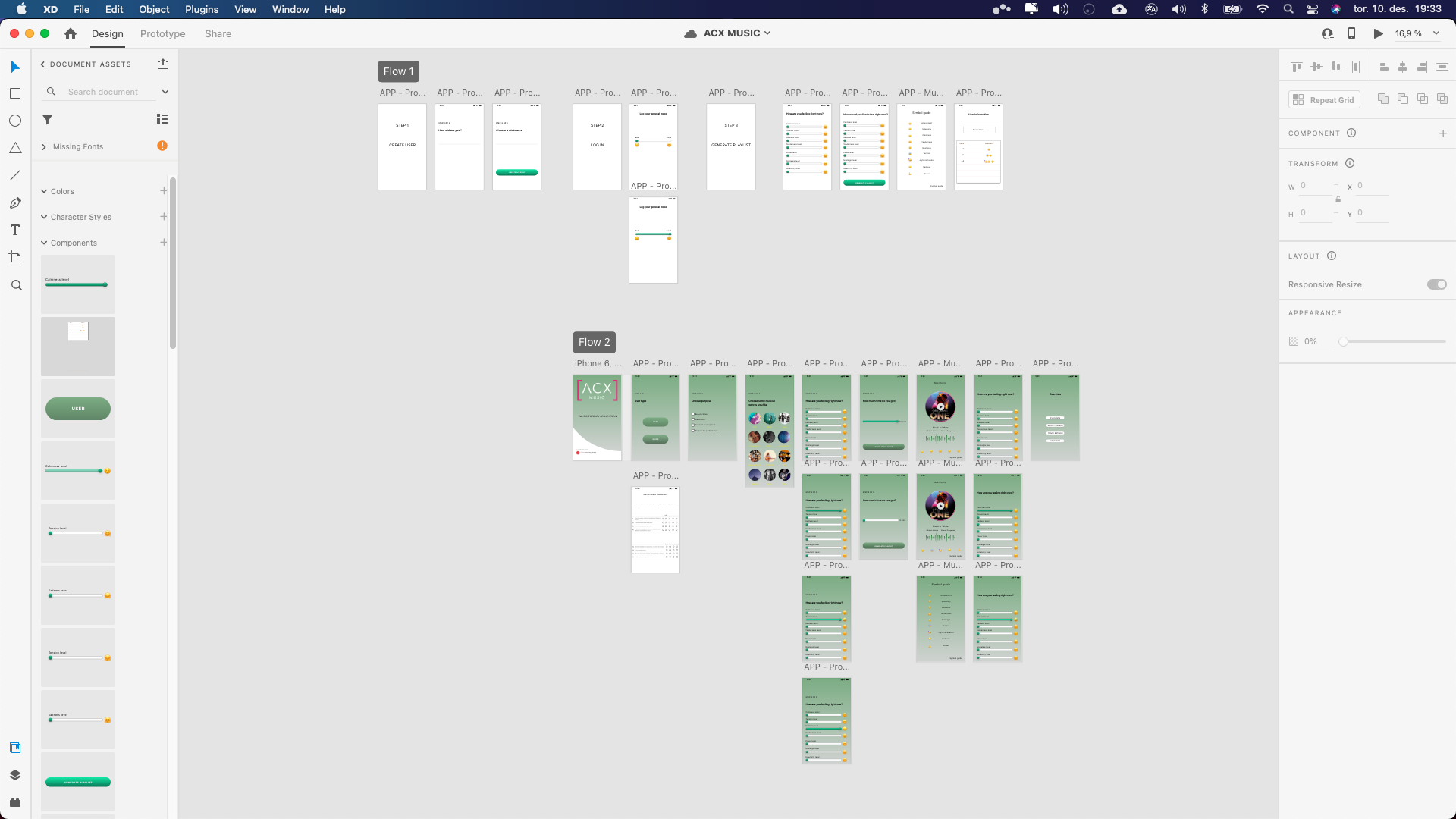

For this project we decided to make a protoype of how a front-end solution might potentially look. This UI-design was made in Adobe XD, therefore it is a purely visual solution with no back-end integration. The main purpose of this part of the delivery is to give some visual reference to how the system might function.

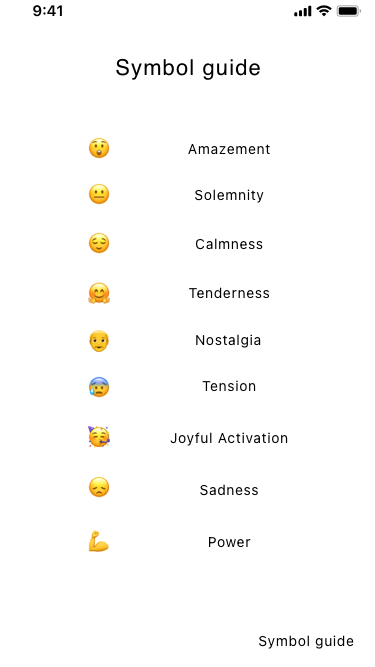

In the overview above you can see two different prototypes (marked with Flow 1 and Flow 2). The first “flow” corresponds with the first system we have suggested. Where the user inputs age and a nickname, rates their general mood and then proceeds to input their current mental state and their desired state before generating a playlist. The different emotional tags are takend from the GEMS scale. The GEMS scale is a list emotions typically elicited by the sound of music. Through research they have tried to pinpoint the most common emoitions evoked by music listening. And this we have used througout our project.

In the picture below you can see all of these emoitions listed with an emoij to go along each emotion. These emoji are use to both input your mental state, but also when you react to the music you are listening to. To either tag the music (System 1) or to tag the features (System 2).

In addition to this we have made some extra artboards where the user can input some more information like musical taste, time restrictions, option for a therapist to use the guide and access to some additional information. This can be seen in the GIF provided below.

Back-end System Design

In the end, we settled for two different approaches concerned with playlist generation and user-data collection. We agreed to this based on the quality of the ideas proposed and our unwillingness to settle for just one. This is not to say that we have to settle for just one system, they can and sould be used in a complimentary way after thorough testing of their strengths and weaknesses.

First Approach

The first back-end system design features a “one-to-one” approach of logging user data together with an experimental approach of generating playlists. For simplicity’s sake, let’s imagine that a user requests a playlist from this system. The user must first specify his/her current and desired emotional states together with a either a time-limit or a number of tracks to include in the playlist. The system then takes steps to find corresponding annotated tracks logged in the user’s profile. If no matches are found, the system looks at other user information before diving deeper into the dataset to find matches.

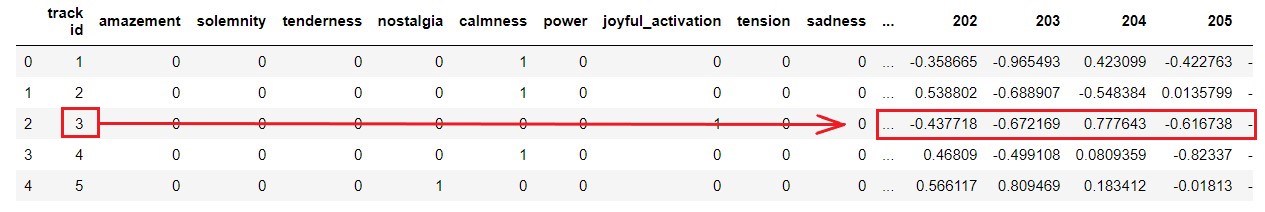

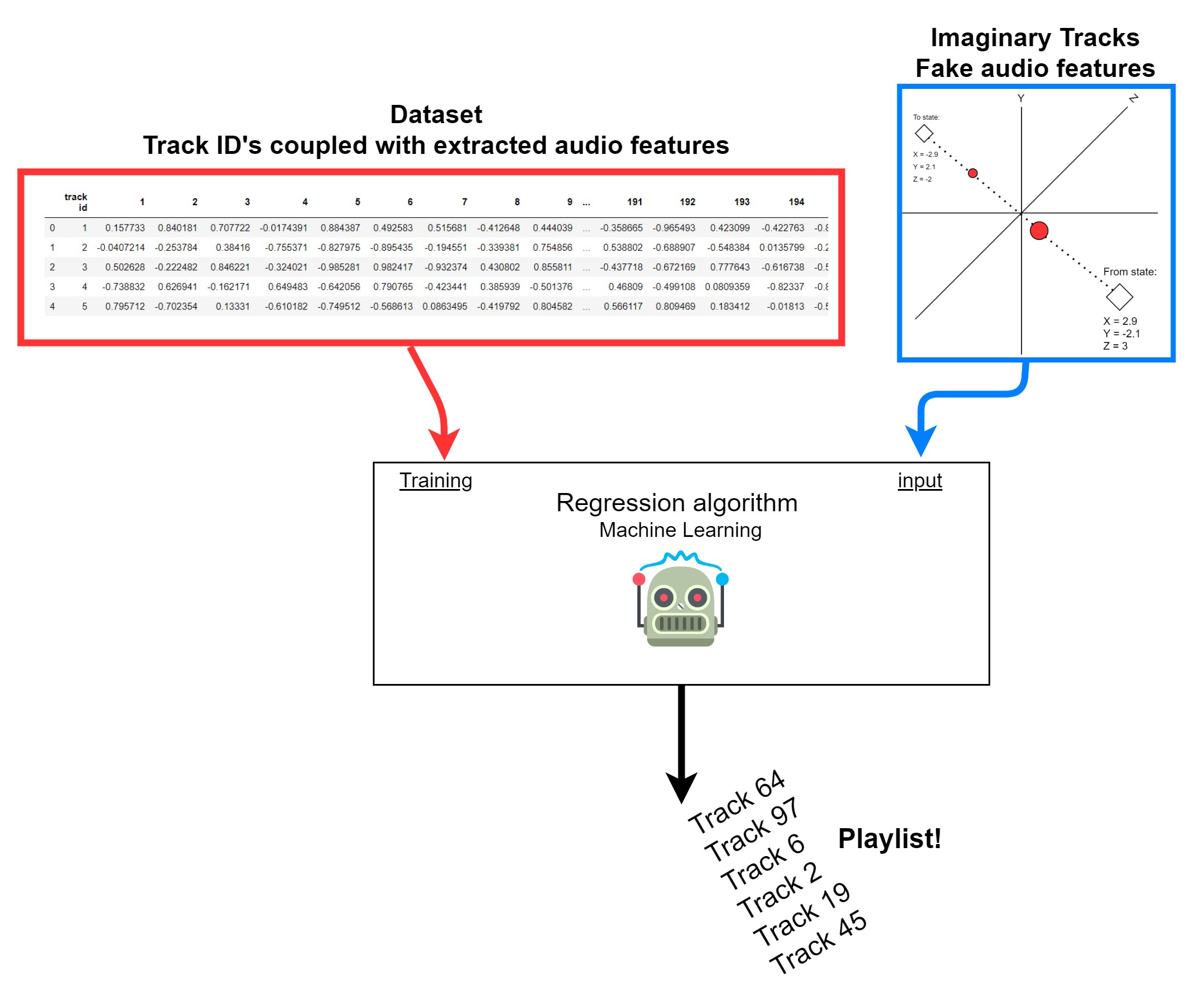

When the system has found two tracks corresponding to the user’s current and desired states, it will locate audio features associated with each of these tracks. As illustrated in image below, this requires us to we have extracted audio features from the dataset tracks.

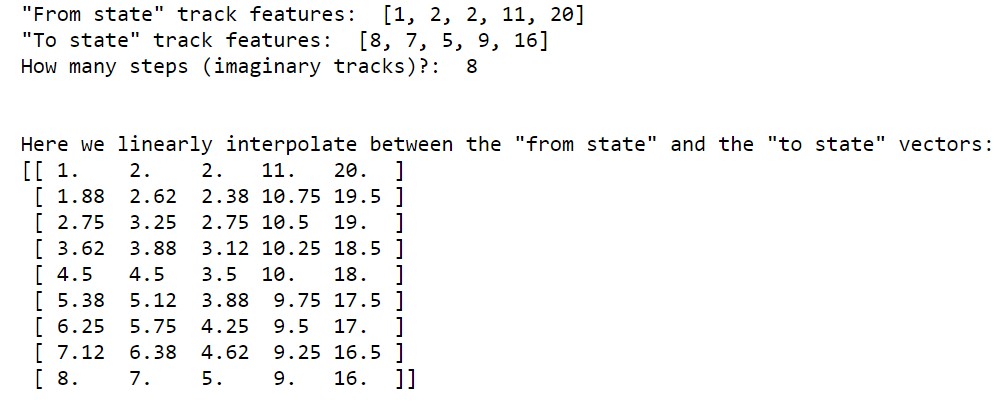

Now the system has two large lists of numbers, each representing audio features. This is where the linear vector interpolation comes in. If the user requests 8 tracks in his/her playlist, the system will generate 8 additional lists by interpolation, as demonstrated below. These additional lists can be referred to as “imaginary audio tracks” as they represent audio features from imaginary sources.

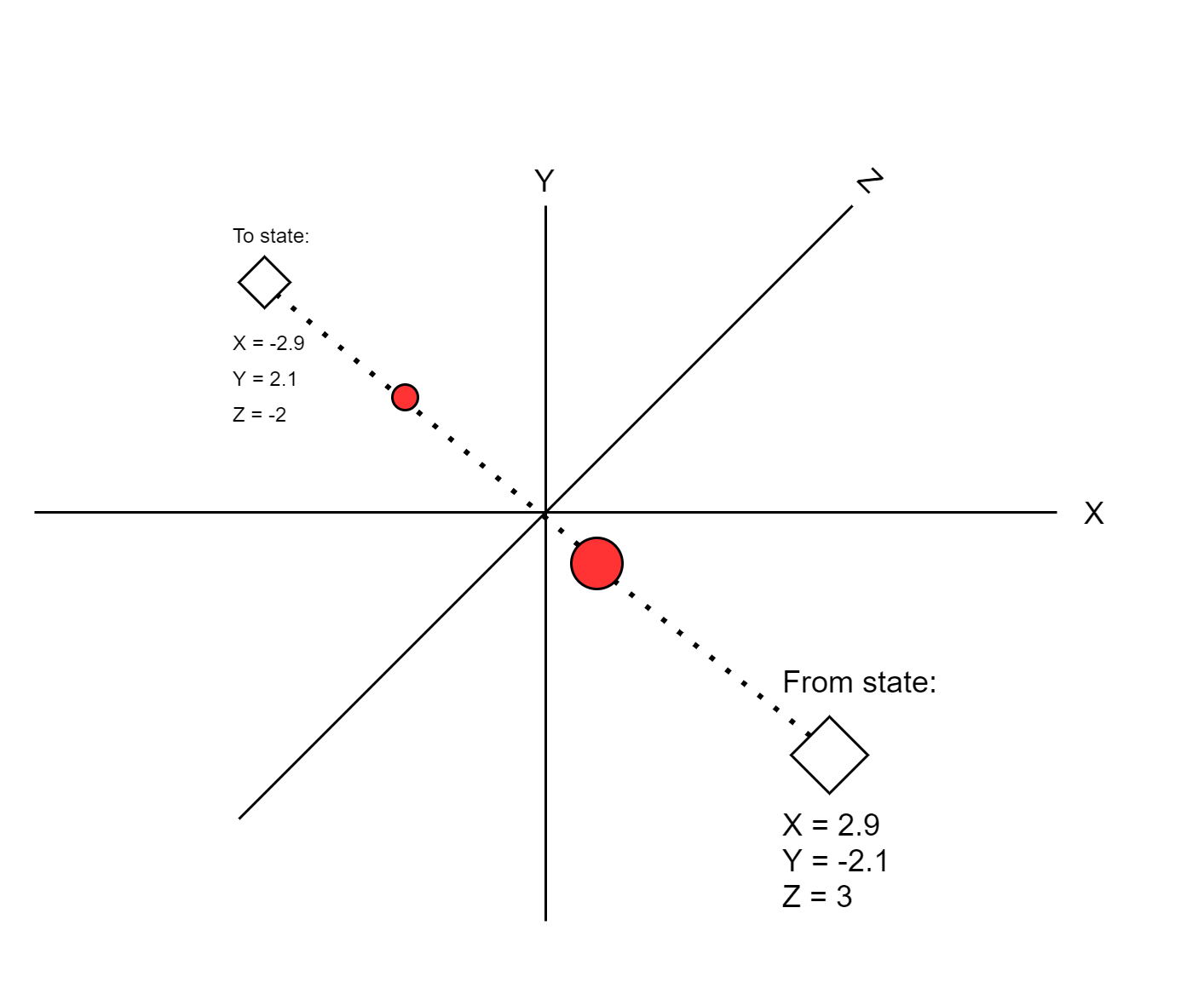

This interpolation process constitutes a “musical journey” through a high-dimensional space, visually represented in the below illustration.

The purpose of these “imaginary audio tracks” is to be used as input to a regression algorithm that predicts which real audio tracks (in the dataset) best correspond to these imaginary audio features. As the visual overview below shows, the output of such an algorithm is track ID numbers corresponding to tracks in the dataset. Together they form a playlist.

Finally, the user will rate the playlist tracks given based on the available emotional categories. Then the tracks and associated ratings are stored in the user’s profile as the cycle continues.

Second Approach

This approach differs from the first one in that it stores what the user associates with features and metadata from the music in stead of tagging the songs directly. The idea is that since taste in music and what emotions music evokes is very personal; making a personal database of what aspects of the music evokes what emotions might be a good way of quantifying this process.

Every person has different conotations to different music. I, for instance get very energized, almost extatic when listening to a certain type of heavy, rhythmic metal. For people who haven’t had very positive, energizing and social experiences to this type of music (most people, I reckon) might have angry or depressing associations with this genre. Like the mirror from the first Harry Potter book; what the viewer sees when looking into it is completely personal and always different from person to person.

Is there such a thing as universally accepted happy or sad music? Maybe. When first starting out building the database of what features and metadata the user associates with the different emotions, using pre-tagged happy, sad, melancolic etc. music can be helpful, but these tags should way in less and less as the user’s profile is built up over time.

Simply explained: If you hear a song that contains features like 100-110bpm, acoustic folk music, from 2010-2020 and so on (the song can have as many features as you like, the more, the merrier) and tag it with “happy and energetic”; the system will store that you associate these features with being happy and energetic. Whenever you want to evoke that emotion again, we simply have to find the song that most closely matches those features.

The beauty of this is it’s simplicity: the system only needs to store a data-table of features on the device and fetch music and metadata containing features from a database, via an API. This maintains both light weight performance and privacy.

Classification and Labeling of New Music

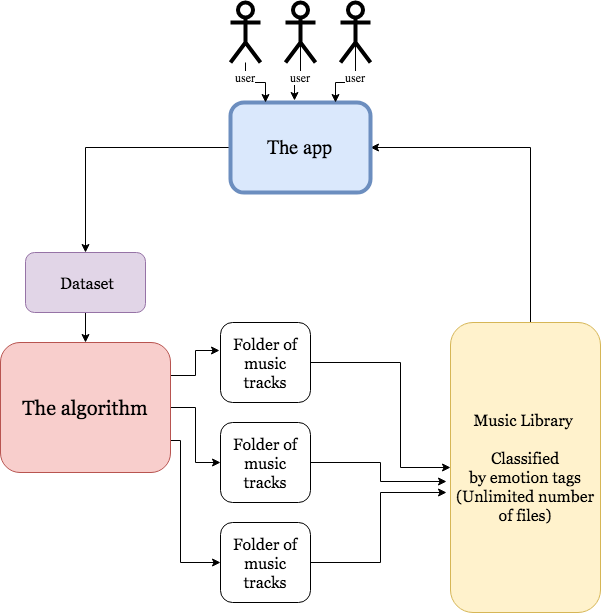

When launching the alpha version of the app, we believe that there might be an advantage for AXC Music to instantly be able to label their whole music library with emotion tags. To provide this, we have created an algorithm that uses machine learning to label music mp3-files with emotion tags. The starting point of this algorithm was the Emotify dataset, which consists of 400 songs in four genres, and uses the GEMS scale for emotion labeling.

We believe that the act of annotating emotions to music is both an individual and complex process, so this model is not meant to replace the human interaction at all, but rather to work together with the users. The users will constantly update the music labels by giving feedback on their personal preferences, but this information will also be given back to the server to improve the dataset that feeds the algorithm. The algorithm will only be used to label new music that is added to ACX’s music library, that hasn’t been listened to by any users yet.

The prototype model consists of two separate Jupyter Notebook files, written in Python and Markdown (the whole folder is a part of our main github repository and can be downloaded from this link ). The first notebook ( ACX_algorithm.ipynb ) is the machine learning algorithm which imports metadata from the Emotify dataset and extracts features via Librosa. If ACX later are in possession of a bigger and better dataset than Emotify dataset, this file can easily be edited with the new dataset. And also, if ACX wants to use other emotion annotations, this should also be an easy thing to adjust.

The Librosa feature extractors used are the tempogram and mfcc. The features are the sound information retrieved for each of the songs, such as BPM, energy and tonality. Tempogram was chosen because tempo often is an indicator of the energy in the song. MFCC is a great feature extractor to detect similarities between sound files, and it is commonly used in speech recognition. The Linear Discriminant Analyzer projects the features and reduces them to a number that successfully separates the different music files from each other by emotion tags.

The machine learning algorithm chosen was the Support Vector Machine, and it performed with an accuracy of 100 %, which means that all of the tracks in the testing set were labeled correctly.

The other Jupyter Notebook file ( ACX_input.ipynb ), imports the algorithm and reuses it to label new music files with emotion tags. When running the Jupyter Notebook, the user is asked to type in the folder that contains the music files (instructions on where and how to place the files is described in this readme file). The result is an excel file that belongs to that folder, with emotion annotations to each song.

So, does it really work?

The algorithm was apparently working very well on it’s own training set, but it is difficult to say whether or not it works well when tested on new music content. This is due to the fact that the dataset was very small to begin with, and only contained 4 different genres. When listening to the newly labeled music, there seems to be similarities between the songs within each of the label, but there are also some songs sticking out as obviously wrong labeled. It is also difficult to do any objective evaluation of the model just by listening, as musical emotion annotation is highly individual.

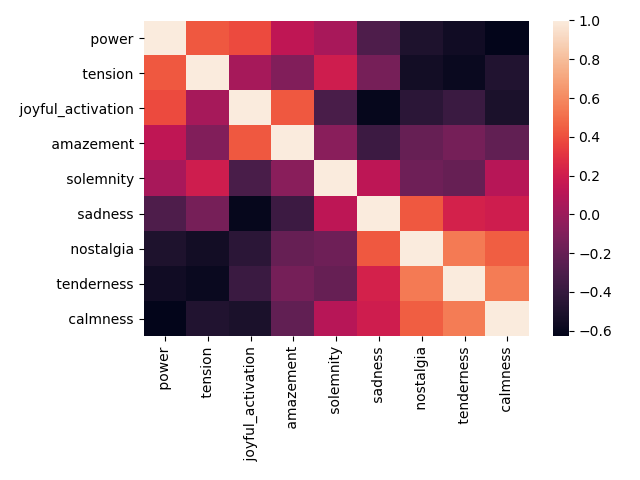

It can also be discussed to which degree the model performs wrong, when misclassifying songs, as some of the emotional categories are close to each other (eg. nostalgia vs. sadness, or power vs. joyful activation). If a “sadness” song was classified as “nostalgia”, did the model perform 100 % wrongly, or could you argue that it was 50 % wrong?

When evaluating the model it might be an idea to range the emotion annotations on a linear scale. The linear way of thinking around the emotion annotations also fits better to the way the rest of the app is working, and should also perhaps be regarded when importing the dataset into the machine learning model. So instead of using the mean emotion annotations, each song should be tagged with a percentage correspondence to each emotional category (e.g. track 1 is 0.20 nostalgia, 0.3 calmness and 0.5 sadness). This way of thinking will probably give a more nuanced and precise classification of songs.

Below, you find a short demonstration video of music that was labeled with the algorithm. The music samples were borrowed from the Emotion in Music Database:

System Evaluation

Our project development did show promising results considering the scope of the project. We succeeded in our goal and managed to prototype various solutions (components of a system) that will generate playlists based on the emotional states of its users. However, a two things are worth discussing.

First, we could have explored using multiple datasets. At the end of the project period, we had acquired multiple equally applicable datasets with emotionally annotated music. Therefore, a solution could have been to fuse multiple datasets. However, we had little time or knowledge on how to best compare them to one another. Such a dataset would have given us more and a wider variety of data that could, in turn, have rendered our systems more accurate.

Secondly, the positive thing about having multiple main system solutions (system nr.1 and system nr.2) is that we address the uncertainties inherent in developing systems without proper testing procedures. The negative side of this approach is not being able to deliver a fully functional system, only a collection of prototypes. When evaluating both back-end system designs now, it seems clear that a combination of the two probably would be the most optimal solution.

Group Challenges

One of our main challenges in this project was the fact that non of us are experienced programmers or designers. We have no prior experience in building such a system from a technical point of view. And it is therefore difficult for us to evaluate how easy or difficult it would be to integrate our solution in a functioning application.

Another challenge we faced was the inability to use third-party streaming services and their API. The external partner has their own database of music, but it lacks usable metadata.Therefore, the database with musical features has to be built from scratch. Which can be very time consuming.We never got access to this database so we were not able to test the system with real music. Since we only used the Emotify dataset, we only had 400 songs with 4 different genres. Which is not enough for building a good ML-algorithm. A potential solution in the future could be to fuse several datasets. However, this would force us to abandon the emotional tags we have used since these are not part of universal standard.

Ethics and Privacy Issues

Like all systems that analyze user interaction data for improvement, privacy is a huge concern. This concern is amplified by the fact that this is a system party intended to be used in a clinical setting where sensitive patient information must be protected as good as possible. The theme of privacy on digital platforms has had center stage in many public conversations in the past years and become more relevant by the day. To use search engines as an example: If you have had a Google acocunt for some years, big brother has hundreds of gigabytes of data on you stored on their servers. This includes location history, searches, all files you store (yes, they never actually delete them), emails… If you put on your tin foil hat and start to dig in to this, it gets really scary really quickly. But have you ever tried to use DuckduckGo as your main search engine? The experience is mediocre at best. The difference between seeing internet filtered and tailored just for you and plain search engine query is stark, but that’s the prize we pay for privacy. We want to build a service that gives the user the privacy they deserve while still providing a highly customized user experience, without selling your dreams and dirty secrets to satan.

We do this in a couple of ways:

- By presenting the user with a very clear switch for turning on or off the stream of data that goes to analysis.

- By encouraging the user to use an alias instead of their real name.

- By having two “modes”, one for use as a tool for therapists and one for personal use.

References

- Aljanaki, A., Wiering, F., & Veltkamp, R. C. (2016). Studying emotion induced by music through a crowdsourcing game. , 52 (1), 115{128. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2015.03.004

- Browning, C. A. (2000). Using music during childbirth. Birth, 27(4), 272-276.

- Eerola, T., & Vuoskoski, J. K. (2012). A review of music and emotion studies: Approaches, emotion models, and stimuli. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 30(3), 307-340.

- Gillen, E., Biley, F., & Allen, D. (2008). Effects of music listening on adult patients’ pre‐procedural state anxiety in hospital. International Journal of Evidence‐Based Healthcare, 6(1), 24-49.

- Grocke, D., & Wigram, T. (2006). Receptive methods in music therapy: Techniques and clinical applications for music therapy clinicians, educators and students. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Lieberman, E. J. (2007). Sacks, oliver. musicophilia: Tales of music and the brain. , 132 (15), 76{77. (Publisher: Library Journals, LLC)

- Norsk forening for musikkterapi. (7 December 2020). Hva er musikkterapi? Retrieved from: https://www.musikkterapi.no/hva-er-musikkterapi

- Ruud, E. (2010). Music Therapy: A perspective from the Humanities. New Hampshire: Barcelona Publishers

- Trondalen, G., & Overland, S. (2008). The Bonny method of guided imagery and music (BMGIM). Perspektiver på musikk og helse: 30 år med norsk musikkterapi.

- Zentner, Didier & Klaus Scherer. Emotions evoked by the sound of music: Characterization, classification and measurement. Emotio (Washington, D.C.), 8:494-521, 09 2008.