Tree as Speakers

Background

In this project, we collaborated with ÅF Engineering. Martin Hallberg acted as our external supervisor and Stefano Fasciani as the internal supervisor. The goal of the project was to create a non-intrusive soundscape and/or noise-masking installations in an outdoor public space by using trees as speakers, installing audio exciters in the root system of the trees. We got information on a similar project by ÅF Engineering, an installation at the Sofiero Park in Helsingborg, Sweden. The installation was called “A fairytale walk”, and consisted of 8 trees, with one transducer on each, playing 8 fairytales. Visitors could then walk from tree to tree and put their ears to the trees to listen. This was inspired by a similar project by MIT, called “ListenTree”.

We were supposed to investigate the following questions during the project:

- What kind of tree/wood gives the best resonance?

- How can we mount the transducers in the root system to achieve the best sound output?

- Do we need one or more transducers to get the best sound quality?

- How far can sounds, emitted by a tree, reach?

- What is the effect (qualitative and quantitative) of having several trees as sound sources close to each other?

- What sound should a tree “play”?

- How should the sound file be mastered so that it can be “played” out of a tree with minimal losses?

- Can sound-emitting trees be used to hide unwanted noise in public spaces?

- How can such systems make noisy public spaces more attractive to people (user surveys, concept design surveys)?

Project plan

Our plan was to do several field recordings, mounting sound exciters (the type of transducer we were to use) to trees in several setups, and then do analysis of the recordings. Tests would be done both in uncultivated areas and eventually in the city. We would play sinusoidal sweeps through the trees, investigating the following setups:

- Number of exciters, on different number of trees

- Placement of exciters (roots, trunk, w/o bark)

- Different recording distances

- Different trees (type, humidity, size)

Analysis would follow, getting the frequency response of all setups. From the frequency responses, research and SPL-meter readings we could be able to answer the questions provided.

Implementation

It all started when we received equipment from ÅF engineering. Two problems arose:

- The amplifiers required a power supply of 32V

sd250 - The exciters were meant for glass application.

sd1g

We knew we would get this type of transducer, but we saw it as problematic to use these outdoors in the cold winter. Luckily, we were able to borrow the same type of exciters from Øyvind Brandtsegg, but with a surface mount plate, made for wood application. This made it easier for us to mount.

We tried to solve the issue of portable power supply in several ways:

- Borrowing an inverter from the electronics department

- Borrowing power from Estenstadhytta in Trondheim

- Borrowing stationary power outlets from Trondheim municipality

- Borrowing a car amplifier (12V) from Robin Støckert and borrowing a 12V battery from Jørgen’s brother, Fredrik Varpe

In the end, it was only the last point that solved our issue.

Before being able to go outside we got familiarized with the equipment and a software called Room EQ Wizard (REW).

Field recordings

At Tømmerholtdammen in Trondheim, a remote and quiet place, two types of trees (birch and spruce) were picked, where we also investigated different sizes.

To improve transmission from the exciter to the tree, we carved out a flat surface. Since we did not have any shovels nor waterproof exciters, we decided to start by mounting the exciters on the tree trunk.

Sine sweeps, exported from REW, and a song from Spotify was played through the tree, using a phone, connected to the amplifier. The recordings were done using a directional condenser microphone, borrowed from Eigil Aandahl.

We ended up with five setups, where we did 5 sinusoidal sweeps, played a song, and measured sound pressure level with a SPL-meter, also borrowed from Eigil Aandahl. The setups are shown in the analysis.

When we listened to the recordings of the first field trip, we could hear that the sine sweep sounded more like a square wave sweep. The gain on the amplifier was set too high, causing clipping. When we went out the second time, we turned it down, and it solved the issue.

Please take a look at this awesome video made by Shreejay, showing the field recording process:

</figure>

Lastly, we recorded the background noise outside Fjordgata 1 in Trondheim City.

Research

Researching wood acoustics, we found that the acoustical performance of wood is determined by density, Young’s modulus (measures stiffness of a solid), loss coefficient and hardness. These physical properties will affect the speed of sound, impedance, sound radiation coefficient, loss coefficient and the eigenfrequency of the tree. (Wegst, 2006)

We also researched auditory masking and found that the sound’s masking ability depends on its intensity and spectrum. When the intensity of a masker is raised, there is an increase in masking upwards, but very little masking at lower frequencies. This is known as upward spread. There will also be strongest masking around the immediate vicinity of the masker frequency, and lower frequencies mask a wider range than higher frequencies. (Gelfand, 2009)

Analysis and results

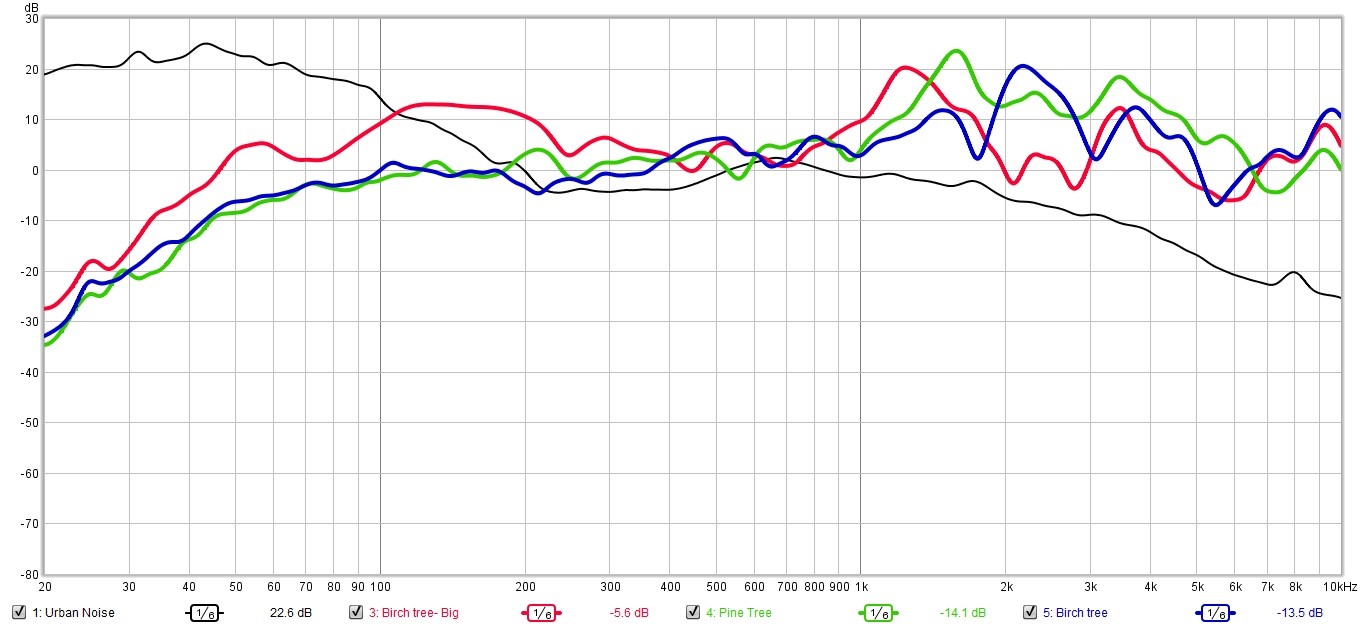

The initial visualization consists of so many data points that made it impossible for comparison. We experimented with different types of smoothing, and landed on 1/6 as the best-applied smoothing. Then we discussed which recordings to compare and analyse.

Summary of Analysis

-

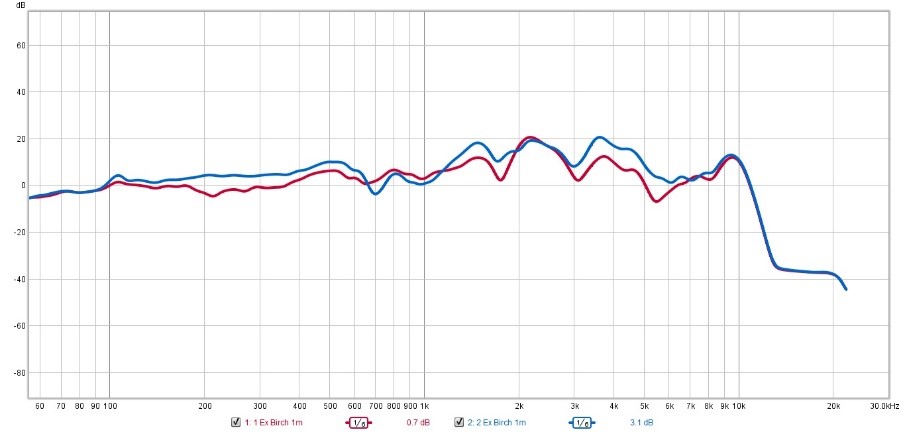

Comparing small birch tree with one exciter and two exciters. The results showed that overall the number of Exciters doesn’t seem to affect the frequency response other than levels.

Blue: 2 exciters, red: 1 exciter -

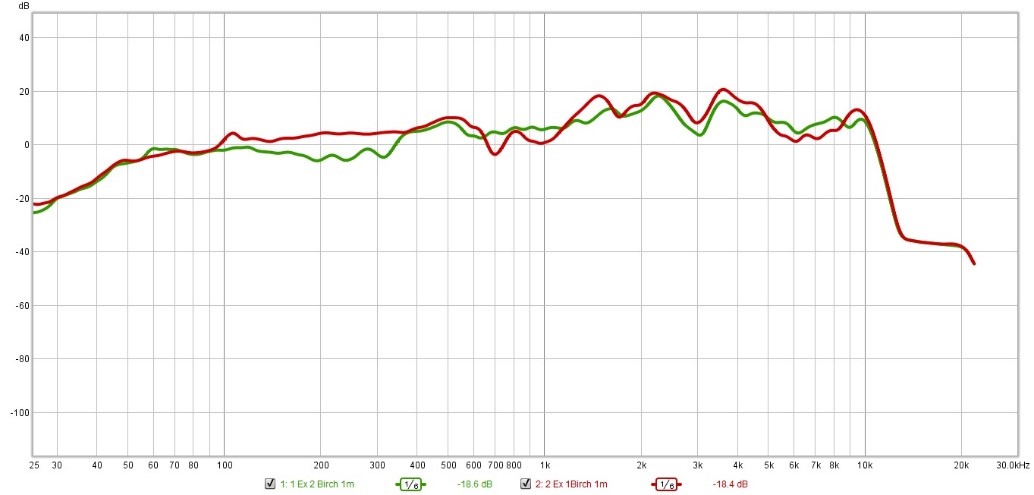

We had to investigate if the number of trees can affect the produced frequency content. From the results, we identified that using one exciter per each tree tends to produce a slight drop in 100 Hz - 380 Hz range. This might be due to microphone placement, pointing between the trees.

Green: 2 trees, red: 2 exciters on 1 tree -

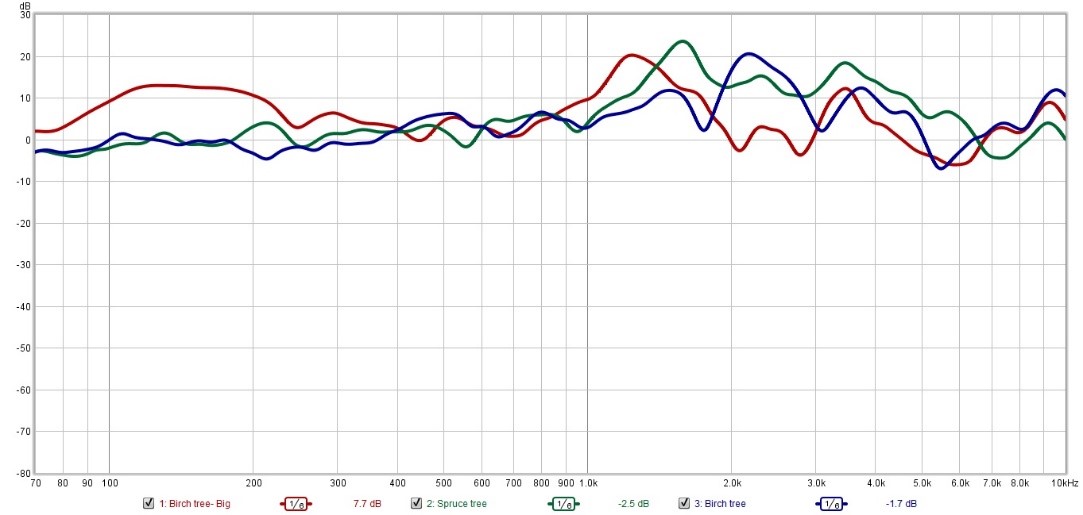

We analyzed the frequency responses of birch, Spruce and the large birch tree. The results were interesting and led to some ambiguity about the recording itself. According to the graph, the large birch tree is producing lower frequencies in the 100 Hz -200 Hz region. Then we had to make sure it was not due to background noise. The recording had a background noise of rain which was not possible to clean or remove during the editing process because it will drastically affect the frequency response graph.

Red: Big birch, blue: spruce, green: small birch -

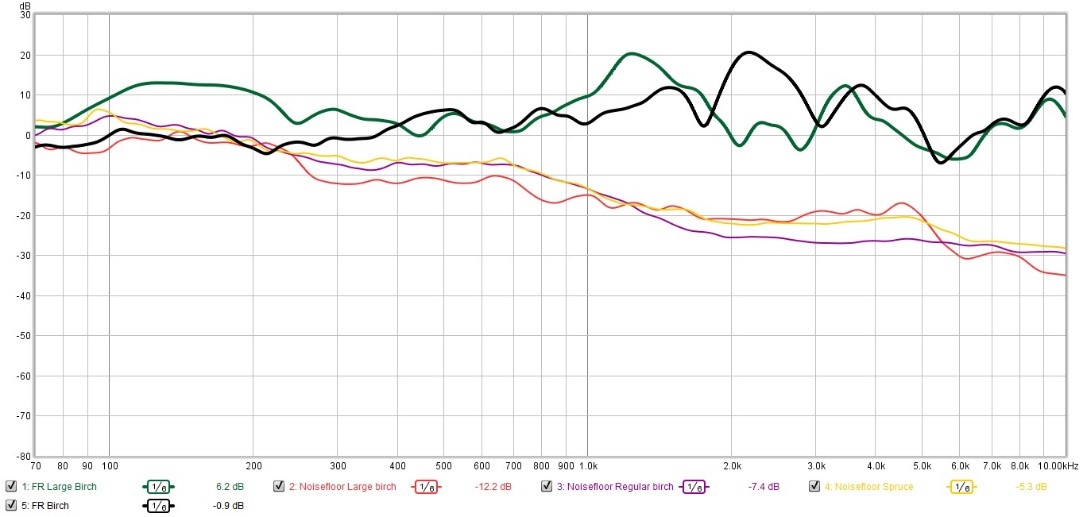

We created frequency response graphs of the background noise in the recording by choosing 1-3s clips of the background noise. And also created another frequency response graph by using the half-length sinusoidal sweeps (so the sweeps will start from 500 Hz- This step was for further confirmation that the low end was not produced by any background noise). As the final result, it suggests that the larger birch tree produces more low frequency content.

Green: Big birch, Black: small birch, red: bg-noise big birch, purple: bg-noise small birch, yellow: bg-noise spruce -

According to the urban noise analysis we did, higher levels of low-frequency content below 100 Hz should be produced from trees to mask public noise. By listening and looking at the frequency spectrum, We realized that vehicles contribute most to the low frequencies in urban noise. We concluded that this kind of system is not suitable for noise masking but more appropriate as sound installations.Trees can be used in office spaces to play background music to break the extreme silence. Also, interactive installations can be done in public parks and children parks. As an example, playing sounds through trees which will trigger if a person gets closer to trees.

Black: Trondheim city noise

Big thanks to all who helped us:

- Robin Støckert

- Stefano Fasciani

- Øyvind Brandtsegg

- Andreas Bergsland

- Daniel Formo

- Eigil Aandahl

- Fredrik Varpe

- Eirik Havnes

References

-

Gelfand, S. A. (2009). Hearing: An introduction to psychological and physiological acoustics (5. ed). New York: Informa Healthcare.

-

Wegst, U. G. K. (2006). Wood for sound. American Journal of Botany, 93(10), 1439–1448. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.93.10.1439