The Shapeshifter

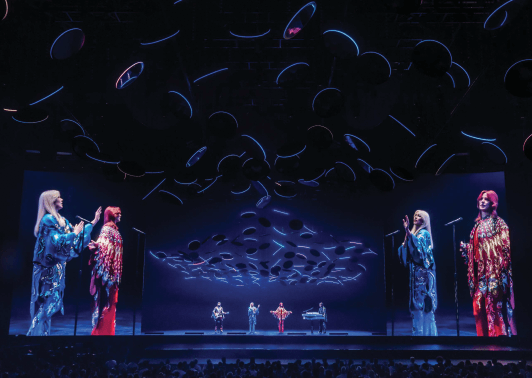

When we use motion capture or tracking (MoCap) systems to capture human body motion for artistic purposes, it can be easy to fall into ways of thinking that conceptually merge the physical body and the representation constructed from the captured or tracked data. A recent, high-profile example of this can be found in the rhetoric surrounding ABBA’s comeback Voyage tour, which features avatars of the members of ABBA as they appeared in the 1970s created through the use of large scale motion capture, with the show’s producer, Ludvig Andersson, employing strong terms to elide the bodies of ABBA and their ABBA-tars, stating that “when you see this show it is not a version of, or a copy of, or four people pretending to be ABBA, it is actually them” (ABBA Voyage, 2021).

However, many actors and technological systems contributed to the production of the ABBA-tars. A team of engineers and animators were involved in the process of constructing the body from the motion data. The technologies involved implied ways of working suggesting the forms that the body can take and what it can do. A number of younger stand-ins even provided the motion from which the virtual body was constructed (Plaete et al., 2022). Although choreographer Wayne McGregor noted that it was a “technical and emotional challenge” to get the members of ABBA “back into their bodies” (ABBA Voyage, 2021), the bodies visible in the show are, in effect, the result of a co-constructive process including all actors involved. In this context, eliding the physical body with representation can lead to the obscuring of assumptions about the body that all these actors bring.

This idea is the central to the research aim of this thesis:

This aim is formalised in the following research questions:

Accordingly, this thesis offers three main contributions:

Although addressing each of the research questions required a diverse set of theoretical, qualitative, and quantitative methods, this thesis is encapsulated in a wider research-creation project. This is a methodological approach focused the combination of research methods and creative practices in a causal manner which leads to academic and artefactual results (Stévance and Lacasse, p. 123). This approach is well-suited for collaboration, and accordingly the work done for this thesis was carried out in collaboration with a performer who specialises in physical theatre and dance.

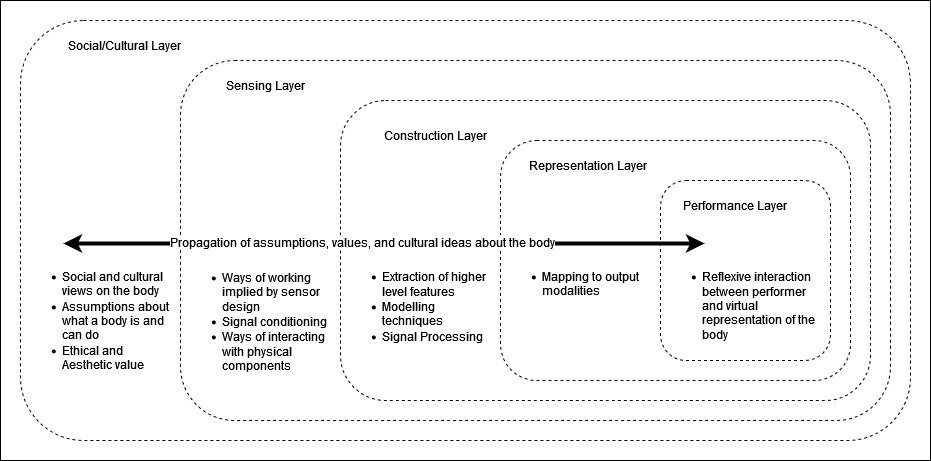

The Co-Construction Model

The main theoretical contribution of this thesis is a model of MoCap in live dance performance as a co-constructive process.

This model was developed to encourage a way of thinking about performance involving the use of motion capture that centres upon critical reflection on the assumptions and values that are embedded in the representation of the body created through the technology’s use. The model depicts this occurring across five layers. These should not be understood as distinct and separated, but rather as nested within one another. They depict the increasing concretisation of the form of the virtual body, until this is realised in performance in relation to the physical body of the performer. Crucially, the flow of the embedding of assumptions and values is not depicted as unidirectional, starting in the outer-most layer and flowing in towards the performance, but rather shows the propagation of assumptions throughout the entirety of the model. Through systematically assessing the locations of actors and technological systems, the assumptions and values that they bring, and how these manifest and interact in the representations that are co-constructed.

The co-construction model was developed upon a methodological foundation based upon the concepts of normalcy, a key concept relating to theorising the body in disability studies (Davis, 1995; Garland-Thomson, 1997), mediate auscultation, in which sensing devices conceptually stand in for that which is being sense (Sterne, 2001), and the propagation of aesthetic and ethical values through the appropriation of sensing devices for artistic practice (Naccarato and MacCallum, 2017).

A full description of the model, how it can be applied as a framework for system design or analysis, and its methodological basis can be found in chapter three of the thesis manuscript.

The Shapeshifter

In view of the co-construction model, together with the research-creation collaborator, we developed The Shapeshifter, an interactive system and peformance to explore the ways in which optical, marker-based motion capture systems construct the representation of the body. With this, we aimed to likewise investigate the performer’s relationship to the representation, as well as the technological components of the system.

The Shapeshifter is an improvisatory dance work for a single performer. Prior to the performance, the performer positions up to 30 position markers wherever they please, either on the body, attached to other objects, or placed within the environment. During the performance, they are also free to reposition these whenever and wherever they wish. A performance consists of nine phases, during each of which the performer improvises a motion pattern and accompanying vocalisations. To trigger the end of a phase, each of the position markers must be located within a corresponding physical space (a bounding box) in the physical performance area. Each phase presents a different visualisation style both for the virtual representation of the position marker and any connections drawn between markers as well as distinct limitations on how the visualisation of each marker can move. At the end of the nine phases, the cycle begins again. During the second run-through of the phases, the performer’s vocalisations for each phase from the previous run-through are looped within the corresponding phase in the current run-through. Starting in the third run-through of the motion phases, the representations of the markers and connections and their motion limitations begin to shift, interpolating between combinations of the representations of all nine phases. The interpolation is based upon several factors, relating to the similarity of the performer’s motion and vocalisations to the motion patterns and vocalisations performed in the previous run-throughs. Likewise, the looped vocalisations begin to twist and distort away from the original recordings. When the performer vocalises during the current run-through, both the audible and visual representations are pulled back into their original state from the first run-through. As the number of repetitions increases, it becomes increasingly difficult for the performer to purposefully control the representations, building to a climax in the seventh and final run-through of the nine motion patterns. A performance takes place with the performer facing a video wall which mirrors the physical capture volume with a virtual capture volume. The audience is also positioned within the performance space, with the performer moving around the audience. To support the idea of the audience being within the performance space, the looped vocalisations are played back over a spatial audio system in two manners. The first is an underlying sound bed that slowly envelops the performance area over the course of the performance. The second positions each vocalisation at the position of the performer at the time that the vocalisation was recorded. The playback shifts between the two techniques based upon whether the performer is currently vocalising. The first technique is used to playback the looped vocalisations with the parameters of the current interpolation applied. The second, to reproduce the vocalisations in their original state.

We employed several quantitative and qualitative evaluations of the system and the collaborator’s performance. A full description of these evalutions, as well as a full technical description of The Shapeshifter system, can be found in chapters 4 to 8 of the thesis manuscript.

Works Cited

ABBA Voyage. (2021, October 13). ABBA Voyage: How ABBA used motion capture to create their avatars. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/ABBAVoyage/videos/abba-voyage-how-abba-used-motion-capture-to-create-their-avatars/399264848445591/

Davis, L. J. (1995). Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness, and the Body. Verso. Garland-Thomson, R. (1997). Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. Columbia University Press.

Naccarato, T. J., & MacCallum, J. (2017). Critical Appropriations of Biosensors in Artistic Practice. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Movement Computing, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1145/3077981.3078053

Plaete, J., Bradley, D., Warner, P., & Zwartouw, A. (2022). ABBA voyage: High volume facial likeness and performance pipeline. ACM SIGGRAPH 2022 Talks. https://doi.org/10.1145/3532836.3536260

Schlemmer, O., Moholy-Nagy, L., & Molnár, F. (1987). The theater of the Bauhaus (W. Gropius & A. S. Wensinger, Eds.). Wesleyan university press.

Sterne, J. (2001). Mediate Auscultation, the Stethoscope, and the “Autopsy of the Living”: Medicine’s Acoustic Culture. Journal of Medical Humanities, 22(2), 115–136. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009067628620

Stévance, S., & Lacasse, S. (2018). Research-creation in music: Towards a collaborative interdiscipline. Routledge. The bigger picture: ABBA Voyage. (2022). Engineering & Technology, 17(6), 14–15. https://doi.org/10.1049/et.2022.0622